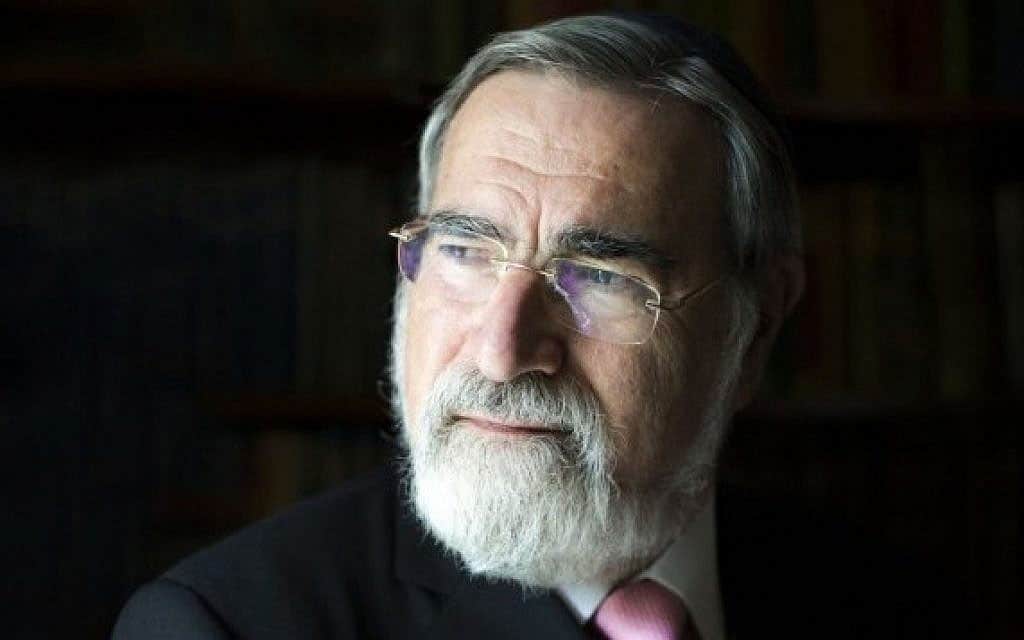

Courtesy of rabbisacks.org

Courtesy of rabbisacks.org The passing of Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks on Nov. 7 has led to an outpouring of tributes from around the world– both Jewish and non-Jewish. When a prolific intellectual giant leaves us, it’s hard to summarize succinctly his unique contribution beyond the usual superlatives.

Indeed, he was erudite, brilliant, deeply connected to the Jewish tradition and knowledgeable of holy texts, learned in secular fields such as philosophy, literature and history, compassionate toward humanity, a unifying force in the Jewish world, and a passionate voice for morality and ethics. He was all of those things and more.

But at his core, I always saw him first and foremost as an intellectual and spiritual activist– a man devoted primarily to opening hearts and minds.

He figured out that the best way to open those hearts and minds was to introduce big ideas. He was the master of what I call Big Judaism, a way of portraying the ancient Jewish tradition as profoundly relevant to our times.

He figured out that the best way to open those hearts and minds was to introduce big ideas.

He did this by framing his exhaustive knowledge of Judaism in a universal context. It was this appealing combination that drove his widespread popularity. A quick glance at some of his book titles illustrates the breadth of this approach:

The Politics of Hope

Celebrating Life: Finding Happiness in Unexpected Places

The Dignity of Difference: How to Avoid the Clash of Civilizations

To Heal a Fractured World: The Ethics of Responsibility

The Home We Build Together: Recreating Society

The Great Partnership: God, Science and the Search for Meaning

Not in God’s Name: Confronting Religious Violence

Morality: Restoring the Common Good in Divided Times

All of those books were rooted in the Jewish tradition, but their golden threads were universal. That was the rabbi’s way of breaking through the apathy toward religion. It was also his way to open hearts and minds to the rich beauty and depth of Judaism and the extraordinary story of the Jewish people.

Even in books specifically connected to the Torah and to Jews, he never lost sight of the big picture.

A book on the weekly Torah portion was framed around the idea of leadership: “Lessons in Leadership: A Weekly Reading of the Jewish Bible.” His latest book, also on the weekly Torah portion, is titled: “Judaism’s Life-Changing Ideas: A Weekly Reading of the Jewish Bible.”

Similarly, his powerful book on Jewish identity, “A Letter in the Scroll,” was framed in a subtle and inviting way. Perhaps that is another word to describe the rabbi: he was an inviter, a man guided by a human desire to have you join him at his table.

He joined plenty of other tables, too. He was secure enough in his Jewish identity that he could engage freely and extensively in the non-Jewish world. In a recent tribute to him in the Mormon paper Deseret News, the writer recalled a radio interview with the rabbi:

“Rabbi Sacks concluded: ‘I think all the divisions that currently exist in society have gone far, far too far. I’m not saying it’ll be easy to reverse any of them. It won’t be. But there is none of them that cannot be reversed. Because all it really needs is openness, respect and a willingness to honor people with views not like our own.’”

The writer added: “Rabbi Sacks regularly made statements that caused his readers and listeners to embark on a journey of discovery. One such: ‘If there is one thing the great institutions of the modern world do not do, it is to provide meaning. Science tells us how but not why. Technology gives us power but cannot guide us as to how to use that power. The market gives us choices but leaves us uninstructed as to how to make those choices. The liberal democratic state gives us freedom to live as we choose but refuses, on principle, to guide us as to how to choose. …

“’The result is that the 21st century has left us with a maximum of choice and a minimum of meaning.’”

In spreading his message of meaning, Sacks was equally comfortable talking to 6,000 Chabad emissaries at their annual convention as he was talking to a Mormon paper. This broad range only accentuated his Big Judaism, which was further enhanced by an engaging and elegant prose that flowed through his writings and public speaking.

Sacks was equally comfortable talking to 6,000 Chabad emissaries at their annual convention as he was talking to a Mormon paper.

I met him briefly at some of his speaking engagements in Los Angeles. In addition to his messages, what struck me was his sweetness, his good nature, and his sense of humor. Maybe he saw that that, too, was an essential part of Big Judaism.

We can all be grateful to Rabbi Sacks for leaving the Jews and the world a “big” legacy that will continue to open hearts and minds for decades to come.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.