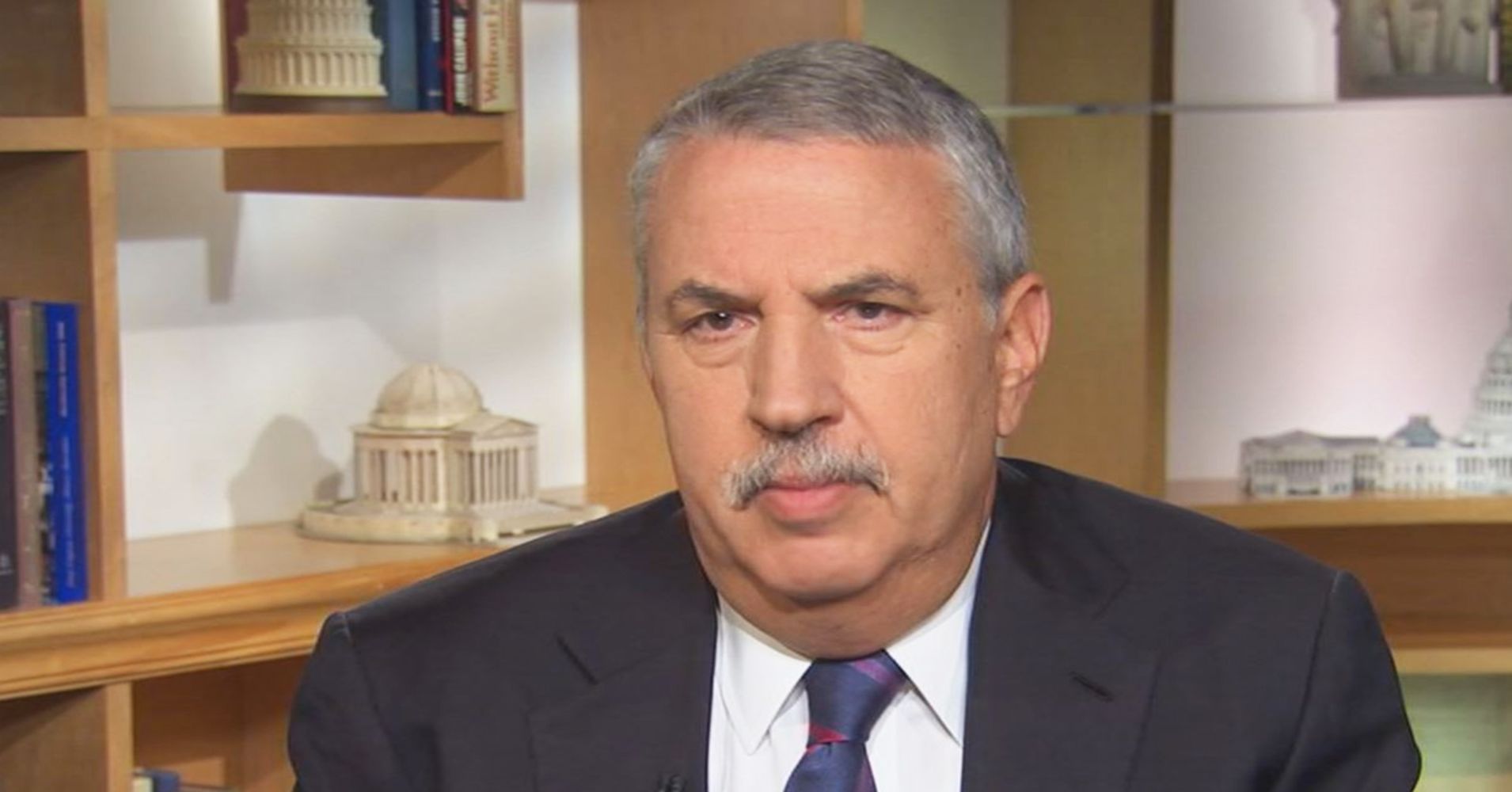

Thomas Friedman, the venerable Middle East commentator, has a problem with the American Israel Public Affairs Committee (Aipac), the pro-Israel lobby group whose mission is “to strengthen, protect and promote the U.S.-Israel relationship in ways that enhance the security of the United States and Israel.”

In his most recent column in the New York Times, Friedman accuses Aipac of being “a rubber stamp on the right-wing policies of Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, which has resulted in tens of thousands of Israeli settlers now ensconced in the heart of the West Bank, imperiling Israel as a democracy.”

When I read that, I thought: What is Friedman asking for, exactly? Would piling on the attacks on Netanyahu really help Aipac’s mission to strengthen, protect and promote the US—Israel relationship? Aipac is a lobby group, not a think tank. As a rule, it respects and honors the democratic choices of Israeli voters, whether they choose Labor leaders like Shimon Peres, Yitzchak Rabin and Ehud Barak, or Likud leaders like Netanyahu, Ehud Olmert and Ariel Sharon.

Friedman seems to blame Aipac for Israeli voters who have put their faith in more security-driven, right-wing coalitions over the past decade. And if anyone is to blame for Israel becoming a more partisan issue in Congress, which Friedman also attributes to Aipac, I would look first at the alarming anti-Semitic, anti-Zionist vibes arising out of new members like Ilan Omar and Rashida Tlaib. If anything, Aipac’s efforts are mitigating this trend.

Apparently, in Friedman’s fantasy world, there’s no end to Aipac’s power. If only Aipac had taken on Netanyahu, if only they had attacked his right-wing policies that have resulted in “tens of thousands of Israeli settlers now ensconced in the heart of the West Bank,” maybe the Palestinian leaders would have come to their senses and a two-state solution would have been more likely.

Never mind that there were already “tens of thousands of Israeli settlers” well before Netanyahu took office, and it was the Labor party not the Likud party that started the settlement enterprise in the first place.

And as much as people may hate Netanyahu, he was still the only Israeli prime minister who implemented a settlement freeze that former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton called “unprecedented.” And despite the constraints of his right-wing coalition, according to a January 2019 piece in the Jerusalem Post, “The growth rate in the settler population has slowed under Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu to its lowest point in over 23 years and possibly its lowest point ever.”

Never mind all that.

In full melodramatic mode, Friedman wants to put the weight of the highest Jewish ideals on Aipac’s back: “I don’t like Aipac,” he writes, “because I strongly believe in the right of the Jewish people to build a nation-state in their ancient homeland — a nation-state envisaged by its founders to reflect the best of Jewish and democratic values.”

Is he implying that Aipac doesn’t believe in all that?

It’s clear that by putting so much undue pressure on Aipac, Friedman is unfairly maligning the group. First, he should know better. He should know, for example, that it’s not Israeli policies—right wing or left wing—that have most stymied the peace process, but the pathological rejectionism of a Palestinian leadership that refuses to do anything that might be good for the Jews or even their own people. Israeli voters have figured that out.

But by implying that Aipac could have done something about an epic failure to resolve an intractable conflict that has jeopardized “the best of Jewish and democratic values,” Friedman is doing more than unfairly maligning Aipac.

Unwittingly, he’s reinforcing the age-old canard of dark, all-powerful Jewish forces that control the levers of power and can get anything done.

No Israeli government, left or right, has succeeded in making peace with the Palestinians. By suggesting Aipac has the power to influence that, Friedman is treating the group the way anti-Semites treat any Jewish lobby group: Too powerful.