Although I have about 40,000 followers on my different social media accounts (Twitter, Instagram, Facebook, etc), I try to engage as many of them as possible. Unless it is a two-way street, the wonderful opportunity social media provides to read countless perspectives might be lost. And while it is hard to separate the “trolls” and the “bots” from authentic users, I do my best.

However, over recent months, I have seen more than the usual hateful and vituperative comments. During this pandemic, shaming and bullying reached a boiling point. And it has been Jews online — some of whom I have met personally and known for years — who have been shameless.

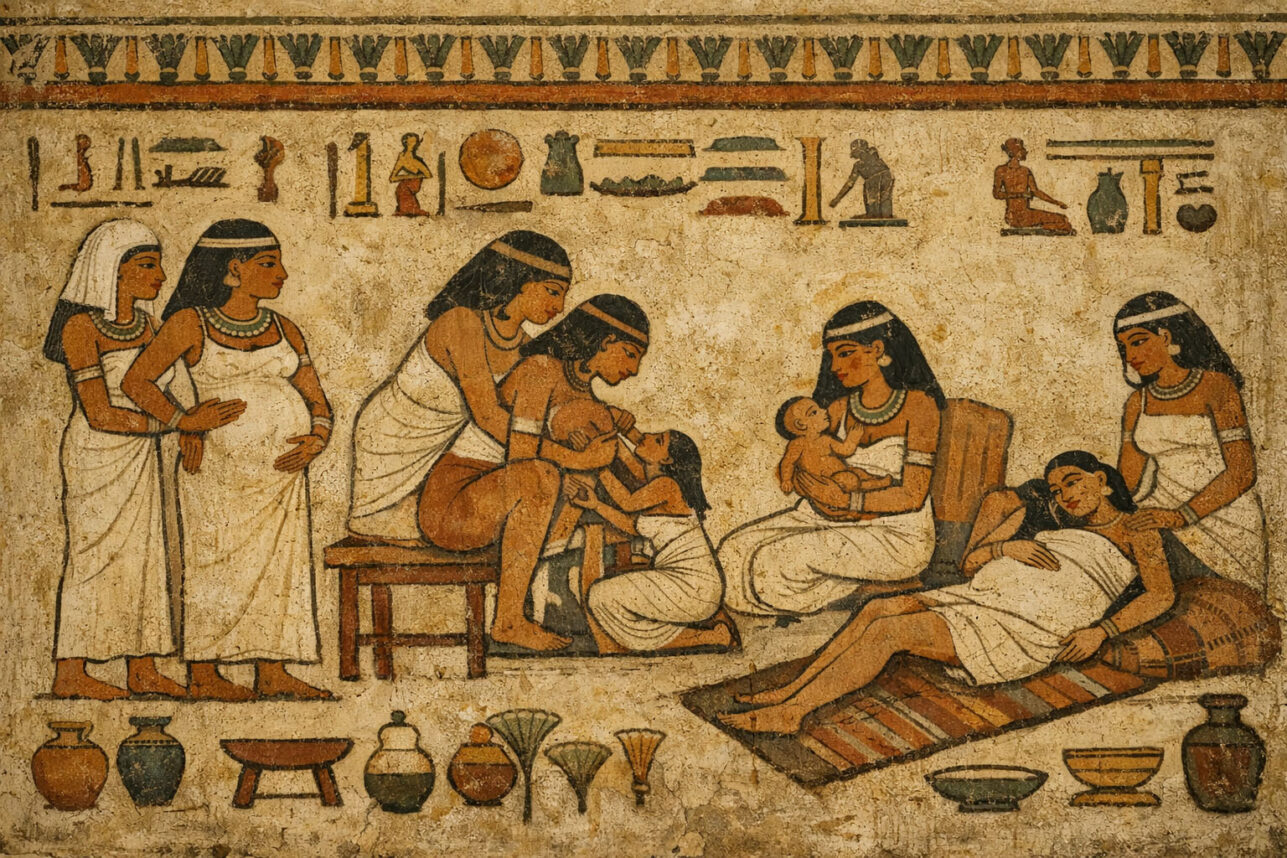

The first emotion mentioned in the Torah is shame. Adam and Eve felt shame for disobeying Hashem, which the Torah describes as a positive kind of shame. As Genesis teaches, shame can be a positive emotion; when one is doing something morally flawed, they should feel shame.

Yet those of us who stake a claim to the moral high ground ought to think twice before we shame others. The Talmud teaches us that “a person would rather experience physical pain than shame” (Talmud, Sotah 8b). Shaming can be as brutal and violent as a physical blow. Later on in the Torah, after Cain killed Abel, Cain’s lack of shame was so problematic that he had to go through a long cleansing process.

The Talmud also teaches us that there are “three signs that signify that a person has a Jewish essence: he is compassionate, ashamed of doing wrong, and seeks to do acts of kindness” (Talmud, Yevamot 79a).

Recently, however, some Jewish social media users have become shameless while remaining intent on shaming others. Numerous Jews have been “doxxed” by other Jews, an assault when your adversaries dig up and mass publish your identifying information, such as your address, phone number and place of work. Sefaria employee Russel Neiss doxxed @ClaireRedacted as revenge for her being “too vocal” in her critiques of left-wing Jews, just months after user Tasha Kaminsky openly offered a monetary prize for Claire’s personal information. As a single mom, Claire felt this violation endangered her young child.

A similar attack happened to Anna Rajagopal from anonymous users in an attempt to silence her left-wing views on racism. Rajagopal, who is 20, then had someone create an account devoted to mocking her. And Kaela Curtis was on the end of a vitriolic bullying campaign in which people publicly accused her of “Jewface” and cosplay because she’s in the process of converting to Judaism.

Now, much of this ugliness online has centered around the California Ethnic Studies Model Curriculum (ESMC). That topic has divided the Jewish community between those who are against the existence of ethnic studies altogether and community leaders who want to have all Jews represented in it. Younger, “online activists” are attacking these seasoned Jewish organizations and leaders, claiming they are “getting duped into thinking antisemitic ideologies” just by supporting ethnic studies in any form.

It hurts my heart to see people threaten and harass individuals, and it also reflects poorly on the Jewish community when we publicly attack — not debate — an ideologically diverse slate of prominent Jewish organizations like the JCRC, ADL, AJC, JCF, Jewish Federation, StandWithUs, JPAC, The Holocaust Museum, JFCS and JIMENA. These institutions and the many volunteers who support them have worked hard to include Jews in the curriculum and remove anti-Semitic content like the Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions (BDS) Movement.

That’s not to say it is unacceptable to speak out, question or debate the way a Jewish organization is run. In fact, last week I asked my Twitter followers what they thought of the little-known fact that the American Sephardi Foundation has an executive director who is not Sephardic. But there is a fine line between debating how an organization is run and claiming that Jewish institutions and leaders are anti-Semites because they do not support one’s own political stance. That assertion is not a valid criticism; it is a personal, if not libelous, attack.

There are legitimate debates and grievances one can have with the Ethnic Studies Curriculum, particularly specifics in the sample lesson plans. However, much of the criticism is of no substance or is just pure misinformation, like false claims that attacks, such as the one on the synagogue in Poway, are “not even on the document” when they are. Even worse, some people are shaming anyone who doesn’t oppose ethnic studies altogether as anti-Semitic.

These instances demonstrate that “the online mob” — as Bari Weiss once called it — knows no boundaries when it comes to shaming the people who disagree with them. When you bully those you disagree with into silence — be it on racism, Ethnic Studies or left-wing politics — the only voices you will hear are your own in a narcissistic echo chamber. Sure, it will be a comforting environment to you, but it is a boring and false one — deception of reality.

When you bully those you disagree with into silence, the only voices you will hear are your own in a narcissistic echo chamber.

Judaism teaches us to distinguish between healthy shame and harmful shame. Too much shame is at the core of anxiety and depression and can lead people, particularly youth, to self-harm. Not having shame at all leads people to dangerous extremes, for example, by doxxing a Jewish single mother and endangering her child or by viciously attacking other Jews who have different opinions than one’s own.

A few weeks ago, a friend of mine, who works at a synagogue, received intense harassment by a Jewish Instagrammer who was not a member of her congregation. It was someone who didn’t even live in the same state. The Instagrammer, who has a Jewish account with around 15,000 followers, was upset that the Temple’s account posted a generic infographic about the definitions of Ashkenazi, Sephardic and Mizrahi Jews. The post was apolitical, as is the synagogue’s account in general. But because this Instagrammer was opposed to these academic standard definitions, she sent threatening and abusive messages to the synagogue. She terrorized them until they removed the post, but by that time, I had already reposted it on my Instagram account.

Ultimately, this Instagrammer threatened to sue the synagogue if it did not compel me, a private unaffiliated individual, to remove my repost. This harassment spanned weeks, with countless phone calls in which temple staff were screamed at and abused. The synagogue tried to get this Instagrammer to talk to me directly about the post, but she refused. Instead, she spiraled onward, threatening a local Jewish organization with frivolous lawsuits. Regretfully, I have become accustomed to these kinds of threats. I would never be swayed to post or not post on that basis. Still, no matter how accustomed one is, it is never comfortable being the target of a violent, unpredictable mob.

I wish I could say this behavior was the irrational nonsense of one deranged individual, but this level of shamelessness in pursuit of shaming others has become the norm. This is an unhealthy shame and unbecoming of an online Jewish community that faces so much real danger from anti-Semitism. This online shaming (which, I admit, I’ve even engaged in a heated moment or two) is not only bad for unity but also strengthens the voices of bullies and misanthropes.

An October 2020 report by researchers from the Georgia Institute of Technology and Harvard Medical School found that “the uncertainties surrounding the COVID-19 pandemic have led to multi-faceted mental health concerns, which can be exacerbated with precautionary measures such as social distancing and self-quarantining, as well as societal impacts such as economic downturn and job loss.” These researchers found that all of the symptoms of vexed mental health have significantly increased during the COVID-19 crisis.

The online attacks on me took a personal toll, exacerbated by the fact I have limited access to the support system I rely upon during non-COVID-19 times. It was truly debilitating to see people calling me names, claiming I hate Jews or Jewish subgroups and even misrepresenting a year-old tweet in Hebrew in an attempt to “cancel” me. These attacks by Jews have been as virulent and irrational as those from white supremacists and anti-Israel activists.

My thickened skin is going to be of little service to the young Jews who are seeing this vitriol, the teenagers who are bullied and the Jews who belong to other marginalized groups that are being intimidated against speaking out about the discrimination they face. Just because youth are being bullied by adults doesn’t mean they can go toe to toe with them without serious emotional damage.

Apologies, my own included, are important to move past this cycle of online shaming. But unless we commit to kindness and good faith as a community, the damage to our youngsters and future leaders may be irreparable. I pose this as a challenge to everyone: for the next month, the month of March and Passover, do not attack individual Jews online. Even if you disagree with them, do not go after them directly; post your comment without attacking anyone directly. I commit to doing this too. The only shame that should occur is a healthy one — the one you feel inside when you fail to live up to your kindest self.

This article has been edited for clarification.

Hen Mazzig is an Israeli writer, speaker and a senior fellow at the Tel Aviv Institute. Follow him: @HenMazzig