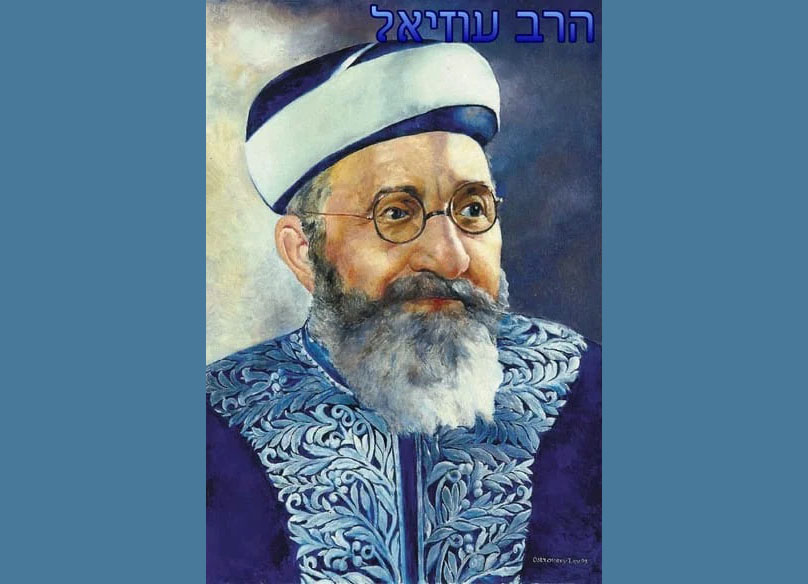

Recriminations

Thoughts on Torah Portion Shemot 2025 (slightly rewritten from previous versions)

© Rabbi Mordecai Finley

Our names give us a stable reference for others, but we, the persons behind the names, know that we live lives of ever-changing senses of self. Our hopes and aspirations, our sorrows and our failures, our losing the way and our finding the road all shift the shape of our inner lives. You might for years tell the story of your life one way, and then the story wears out. You might discover that your story contains facts, but little truth. We have to retell our story. Maybe something happened. Maybe life happened.

Several chapters of our stories will begin with the words, “I was not prepared for what happened next.” The turn of events might create loss, sorrow or confusion. The turn of events might open a door to new love, or to an old love, become new. The turn of events might produce wonder, deepened purpose and resilience.

We are never fully prepared for the turns in the roads that are taking us away from that from which we are running, or from the roads that take us toward that for which we are searching. Sometimes things arrive on the road that have been searching for us.

Take Moses, for example. We are told in our Torah portion (in one long sentence) that Moses grew up, went out to his brethren, saw their suffering, and saw an Egyptian man (ish Mitzri) striking a Hebrew man (ish Ivri) of his (newly found) brethren. Moses looked around, and seeing no one, beat an Egyptian man to death and buried him in the sand.

We are not told that Moses investigated the matter, to find out what might have caused the Egyptian man to strike a Hebrew man. Maybe the Hebrew man hit the Egyptian man first. We typically assume that the Egyptian was a taskmaster, but the text does not say that. Maybe he was just some Egyptian guy. Moses went out to see his brethren and killed someone instead.

We can look long and hard at the story, and at the Midrashic depths of the story, to explain away the manslaughter. The facts as presented in the Torah, however, are sparse and rather horrifying.

When he killed that Egyptian man and buried that body, Moses buried a former self. He was no longer, internally, an Egyptian. He had changed sides. Whatever the killing was about, it was partly because the man was an Egyptian. Moses killed off his Egyptian self. Moses had killed someone, someone who maybe did not deserve to die. Moses had done something, it seems, from a newly discovered inner identity, but a terrible deed nonetheless. Moses went out to see his brethren, and ended up destroying his old identity.

We have all buried former selves, especially the former self that thought it knew who we were, what we would do, and how things would turn out. Sometimes that new reality can hit us upside the head like a brick. Maybe even a brick of our own making. Maybe we even had to find the straw to make that brick.

When Moses went out to meet and greet his people, he couldn’t have imagined he’d return home with blood on his hands.

He went out the day after the murder, to return to the scene of the crime. He took with him, apparently, with of his old sense of self as a ruler. Adopted son of Pharaoh. New person, new people, but the same status.

When he went out the second day, Moses saw two Hebrew men beating each other. I wonder if this gave Moses pause. Maybe there was a gang of Hebrew ruffians about, ruffians who liked to fight, and one of them had attacked the Egyptian the day before. We, like Moses, don’t know what happened before the Egyptian man was beating the Israelite. The Torah averts her eyes when we start to ask.

In any case, Moses soon began to lord over the Hebews. He said to the wicked one, “Why would you strike your fellow?” The Hebrew man, characteristically, it turns out, answered a question with a question. “Who made you a dignitary, a ruler and judge over us? Are you going to murder me like you murdered the Egyptian?” Impudent ruffian. Moses became fearful and said to himself, “Apparently, the matter is known.”

Moses had buried the perhaps innocent Egyptian man’s body, but that did not cover up the deed. It seems that the man whom Moses had saved from the Egyptian had told everyone about the incident, including where the body was buried. We now see the man whom Moses had saved in a new light. Maybe the Hebrew man whom Moses had saved was not only an impudent ruffian, but also a gossip. Maybe the Egyptian man whom Moses had beaten to death was beating the Hebrew man for good reason, impudent, ruffian gossiper that he was. In the olden days, some people deserved a beating now and then. Maybe the Egyptian man of yesterday was no worse than the wicked Hebrew man of today who was beating his fellow Hebrew. Moses didn’t kill him.

Pharaoh finds out and seeks to kill Moses. Perhaps the Pharaoh had read a bit of the not-yet-in existence Bible, “Whosoever shall spill the blood of man, by man shall his blood be spilled.” Moses heads for the hills (of Midian).

Earlier that week, the biggest decision in Moses’ life might have been whether to order the tilapia or the mullet at the Nile Bar and Grill. Now he had to decide which road to take to evade an Egyptian posse. One rash, thoughtless act, and everything was changed forever. I can’t imagine even Moses being prepared for that. His name was still Moses, but he wasn’t the former Moses anymore.

How does he tell himself his story while hightailing it out of Egypt, or for the next 40 years, for that matter? How often does he go over those two days, over and over again, asking himself: “Who was I that I could do that? What was I before I did that? Did I know that I was the kind of man who could do such a thing?” He did the crime and now he would have plenty of unstructured time to think about it.

(I wonder if when Moses heard, “Thou Shalt Not Kill,” he thought, “oops.”)

Look in your past. Most of our offenses are petty, but some are egregious. Did you know how petty you could be, or how destructive you could be, the day before the deed? How do you account for your offenses? We all know this: you can’t bury the wayward self for long. The matter is known. The wayward self shakes off the dirt, or sand, and reappears.

We all have roads before us, the roads of denial or the roads of transformation. Bury the wayward self, or meet it on the road and work things through.

Subsequent events tell us that Moses took the road of transformation.

All of this is recorded in the yet-to-be-written “Journal of Moses’ Recriminations and Rebirth.”

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.