Part 2: The Timeline of the Shooting

This multi-article series revisits the available evidence and reporting around the shooting death of Homicide Detective Sean Suiter on November 15, 2017, adding analysis and some new information to the conversation so far. This information is provided in advance of the findings of an independent panel, commissioned by the department, that has promised insights and recommendations.

This first article looks at the trajectory of Commissioner Kevin Davis in his handling of this case in media and similar cases in the past. Part 2 deconstructs the reported timeline of events, comparing it to police audio records. Part 3 considers the ballistics discoveries and evidence. Part 4 looks at the emergence of the suicide and other theories, as well as the role of the federal government. The Addendum looks at the video evidence, released with the findings from an Independent Review Board. The Conclusion enhances the audio and video further and arrives at a homicide conclusion.

“A very short amount of time”

Most of what the public has been told about Detective Sean Suiter’s death comes from Baltimore Police Department (BPD) Commissioner Kevin Davis’ seven press conferences during November and December; media reporting during those two months; and a follow-up Baltimore Sun article on March 22, 2018, written by Justin Fenton and Kevin Rector. Closely examined, these reports present some gaps and inconsistencies, especially when compared to police and fire audio from that day.

One conspicuous omission has been the timeline of events. BPD’s original media release only said that Suiter was shot “about 4:30pm.” BPD generates Computer-Aided Dispatch reports for every call, so they know the entire timeline. In fact, BPD removed Suiter-related calls from an open source database, limiting the public’s ability to plot out the timeline, as discussed below. The department claimed to want the help of local residents in finding the shooter but withheld what happened when.

Davis and his media spokesman, T.J. Smith, gave one repeated hint about the timeline: It all happened “very quickly,” in a “very short amount of time.” Looking closely, it appears to have been very tight indeed, almost improbably tight at times.

This article deconstructs the reported timeline without theorizing about his death. Timestamps are determined from concrete evidence (911 or dispatch calls) or deduced from the information provided. Some of the deduced timestamps depend on the events having happened as reported by BPD, as discussed.

First sighting of the suspect – about 4:15pm

Davis reported that Suiter was on Bennett Place in West Baltimore on the afternoon of November 15th with a “back-up partner,” following up on a 2016 triple homicide. The Baltimore Sun and activist group Baltimore Bloc identified this person as homicide detective David Bomenka, which BPD neither confirmed nor denied. Eventually, Davis acknowledged that Bomenka was not a part of Suiter’s 2016 case but was “investigating a murder in that area as well.”

On the night of Suiter’s shooting, Davis provided a description of the suspect that became the focus of a week-long manhunt – an “adult African-American male, wearing a black jacket with a white stripe on the black jacket.” Yet, about an hour after the shooting, a dispatcher issued a citywide look-out in reference to Suiter’s shooting for a black male with “white sleeves” and a “baseball cap” that had the unusual detail of being in the “knit style.”

The residents of Harlem Park suffered days of unconstitutional stops and searches based on Davis’ certainty that the person Bomenka identified was the killer. In later press conferences, the commissioner walked back his initial description, somewhat. He suggested it came from a tip, then admitted it came from the partner. But he never said that it might have been miscommunicated.

The twenty minute gap – about 4:15pm to 4:35pm

According to Davis, Bomenka described both officers seeing a stranger who was “engaged in suspicious behavior” in the vacant lot. About twenty minutes later, Suiter entered the lot and was shot. Bomenka did not see the stranger the second time. It follows that the suspicious man and the shooter were not necessarily the same person. Twenty minutes is a long time between police events, and the lot has another entrance.

As pointed out by @bmoreprojects, we’ve been given no information about what Suiter and Bomenka were doing during that twenty minute gap. They were investigating two murders, but nobody has come forward describing any interaction with them. That information would likely have been released, as it would have supported Davis’ story.

Fenton and Rector touched upon the twenty minute gap in their March follow-up story:

Police have said that 20 minutes before the shooting, Suiter and Bomenka saw a man who was acting suspiciously. That observation formed the basis for a vague suspect description — a black man wearing a black jacket with a white stripe — released by the department.

Suiter directed Bomenka to a position around the corner from the vacant lot. Sources say surveillance footage shows the two separate, with Suiter pacing back and forth near the entrance to the lot. The footage shows Suiter darting into the lot suddenly, gun in right hand and his radio in his left hand.

This account conflates the two sightings of the suspect. It gives the impression that the officers separated and stayed there for twenty minutes, staking out this one man – as if they were working on a narcotics bust and not two murder investigations. If there is surveillance video, it should also be able to provide a more detailed account of what happened during these twenty minutes.

Suiter’s shooting – 4:35pm or 4:36pm

On November 22, Davis acknowledged that Suiter was shot with his own weapon. In fact, he said, Suiter recorded it happening:

There is a radio transmission, a very brief radio transmission made by Detective Suiter. It was about two or three seconds. It is unintelligible right now. We don’t know exactly what he said, but he was clearly in distress. The FBI is working with us to enhance audio of that radio transmission. And in the background… was the apparent sound of gunfire… Detective Suiter had his radio in his left hand. And we know when we found Detective Suiter – and again, we have have body worn video of the responding patrol officers… [that his] radio never left his left hand.

From the beginning, there were odd details around this call. (It wasn’t captured by the public scanner that roams the dial looking for activity, so the public has not heard it.) For one, Davis expected citizens to believe that, in a struggle for his life, Suiter chose not to use both hands. Also, if this call was supposed to be a cry for help, then Bomenka was around the corner with a firearm. Suiter could’ve called out to him. And gunfire is loud; the radio was in Suiter’s hand; shots would not be heard in the “background.”

By December 1, Davis seemed to somewhat walk back on the existence of this already uncertain call, in his characteristic way:

The radio transmission that is unintelligible — and the FBI made every effort to enhance it, and they can’t enhance it — it’s still, to me, a two-, three-second radio transmission made by Detective Suiter that is clearly made in distress.

“To me”… Davis continued to refer to this call in exactly this way, as something that was his personal belief.

As for the detail that Suiter’s radio “never left his hand” after he was shot, this may have been a medical miracle. Fenton and Rector described the trajectory of the bullet that killed Suiter: It “entered behind his right ear and traveled forward, exiting from his left temple.” According to Walter Reed trauma specialist Lyz Moore, if that trajectory is accurate, then Suiter “would have lost the ability to keep his hand clutched”:

If there is disruption of the corpus callosum – the bridge in the middle – then messages from right to left or left to right can’t go through. It in effect cuts the phone lines. The left brain can’t send or receive messages from the right hand and vice versa.

Two days after Davis first announced the existence of this recording, CBS21, a local Harrisburg, Pennsylvania station (near where Suiter lived) claimed to have obtained it.

“For the first time we’re hearing recordings of the last radio transmission from a Baltimore detective shot and killed last week,” anchorman Albert Gnoza announced. Their three-second audio sounds like someone breathing heavily, followed by someone else saying “hello,” followed by the first person saying something like “yah.” The station’s audio ends there.

On the scanner archive, the same recorded call lasts another second longer, but it doesn’t end with a gunshot sound. It ends with a dispatcher calling out, “954, what’s the location?” 954 is a call number for a member of the Southern District. Less than a minute after later, the dispatcher issues a signal 13, or “officer in distress,” call, for “Frederick and Pulaski for 954 in the Southern.”

So the heavy breathing call wasn’t Suiter, unless everything we know about his death is completely wrong (a possibility). It’s understandable why someone might have thought so. It was related to a signal 13, just minutes before another signal 13 was issued for Suiter. The existence of the earlier signal 13 is certainly curious; it was cancelled one minute later. (In fact, at the same time, fire dispatch put out a call for all fire units to go to the same street at the same time; that call was cancelled immediately too.)

The existence of the CBS21 story is maybe more curious. I reached out to Gnoza. I asked if someone had sent them the audio or if their own investigators had dug it up. He responded with refreshing candor: “I’m assuming it was sent. We normally don’t dig too much. Lol.” So, someone leaked this audio to the station, but a truncated version of it that removed any reference to it being part of another call. (One lesson of the Freddie Gray case was that the false leaks get sent out of town.)

In a November 28 interview, Smith admitted that this call was not Suiter. The question remains of whether Davis ever thought it was. He had jumped the gun on evidence before.

Bomenka’s 911 call – 4:36pm

Davis announced the discovery of surveillance video on November 22nd, which seems to have come from a corner store. It caught Bomenka making a phone call: “Upon the sound of gunfire Detective Suiter’s partner sought cover across the street and he immediately called 911,” Davis said. “We know this because it is captured on private surveillance video that we have recovered.”

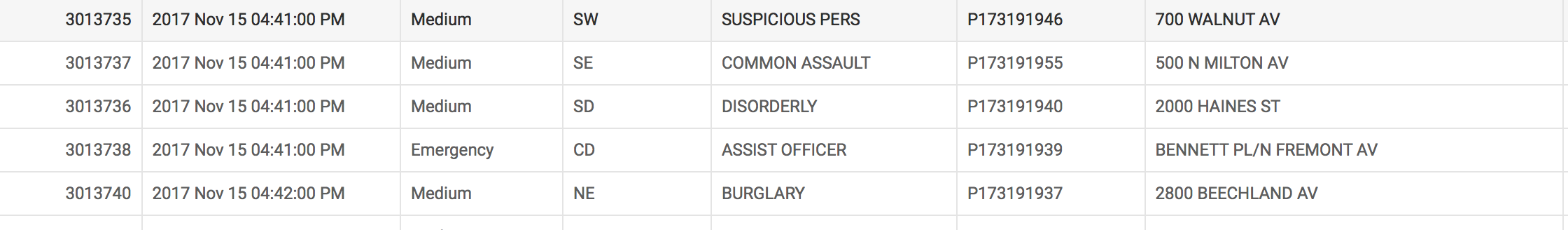

Davis said that Bomenka used his cell phone to call 911 because he did not have his radio on him that day. This 911 call did not originally appear in the Open Source database of emergency calls, raising suspicion among some on Twitter:

At some point in the last two months, this call was returned to the database. At 4:36pm, there is an “Assist Officer” call for Bennett and Fremont:

As these two images show, many other calls around Suiter’s killing were removed in November 2017 and have since been restored. The database now shows another “Assist Officer” 911 call at 4:41pm for the same location.

Meanwhile, Davis’ revelation that investigators found security camera footage rang some suspicious bells for me. Back in April 2015, Davis announced that the Freddie Gray task force had discovered a third stop on security camera footage from a corner store. It reportedly showed the van driver pulling over to check on Gray, then getting back in the van and continuing to drive. The video played a big role in the medical examiner’s findings and the charges against the driver.

When the footage of the third stop was finally played in court, it had no time and date on it, and it didn’t definitively show Goodson. It was entered into evidence as a video of someone filming a video being played on a screen. So, it would be helpful to verify the authenticity of the security video in the Suiter case.

Signal 13, Officer in Distress – 4:38pm

At 4:38pm (sometimes misreported), the dispatcher issued a signal 13, which called all available officers to the scene. Her description of Bomenka’s 911 call stands out:

Be advised in reference to the signal 13. It says, call reported that his partner got shot. No description of the suspect. No further. Be advised. It came in with a name. It said “off-duty.”

The dispatcher may have misheard or mistyped. Otherwise, Bomenka announced himself as “off-duty.” He didn’t provide his identity. Davis had said that Bomenka was on duty, investigating a case. Maybe he was off-duty. He didn’t have his radio. Or maybe someone else called in the shooting, who didn’t want to be identified. If it was Bomenka, he also didn’t provide any information about the shooting. Officers typically communicate a lot of information during a high-priority police event, and this event was of the highest priority.

University of Maryland call – about 4:39pm

Almost two minutes after the dispatcher announced the signal 13, she announced that Bomenka was headed to University of Maryland (UM) Shock Trauma, about a mile away: “Central city dispatch to the University of Maryland… At trauma, be advised, I’m going to have an officer enroute to the location… We’re gonna need to start shutting down some streets for the medic.”

This is where the timeline gets extremely fast. Smith said that officers arrived wearing body cameras “within two minutes” of the signal 13 and filmed Suiter on the ground. But Bomenka was already planning to leave within two minutes of the signal. Within three to four minutes, they were in a car accident. Davis and Smith benefited from some of these times being incorrectly reported by media, including an earlier signal 13.

First responders – 4:38pm-4:40pm (unclear)

Perhaps the haziest aspect of the timeline involves the first responders to the scene, by which I mean officers who arrived before Bomenka left with Suiter. On November 17th, Smith said, “Officers arrived on scene pretty much immediately. And based on where they were, they felt that they were in a better position to take Detective Suiter to the hospital quickly to Shock Trauma.” Davis praised their “split second” decision to not wait for a medic.

Usually, Davis and Smith spoke about multiple first responders, with multiple body cameras that filmed Suiter on the ground. But on occasion, they made it seem like there was only one. “The officer called 911 and dispatch immediately summoned other police officers and medics to the location,” Smith summarized. “The first arriving police officer got there. They loaded Detective Suiter into the car.”

A patrol officer is sometimes mentioned, but nobody else. A civilian witness described to WJZ seeing one responder with Bomenka, though the interview is rather short. (BPD interviewed many witnesses and did not share any of their accounts with the public.)

These first responders – their statements and body cameras – have been very influential to the public’s understanding of Suiter’s death and theories of his death. Their actions are incredibly fast and, like Bomenka, they do not have much presence on the radio. I couldn’t make out their call numbers. At the least, we should be told how many officers responded initially and at what times. Again, there is supposed to be security camera footage. It shouldn’t be a mystery.

Second wave of responders – arrived by 4:42pm

By 4:42pm, several officers are heard on the radio at Bennett Place. A supervisor tried to get control of a confusing situation:

I’m not sure what house we’re looking at but apparently there’s an armed person inside of, uh, Bennett Place… We don’t know if it’s from a house or in the alley… We have officers in bad locations. Let’s everybody take cover somewhere. Okay? Get away from them windows… Because we don’t know where the shots came from. Everybody get covered until we figure this out please.

This supervisor became increasingly frustrated. By 4:50pm, he still did not know anything:

We still have a possible armed perp here… Officer was not able to speak on where it came from. We don’t know if it was on foot, in the rear alley, or from one of the houses near the window. We’re not sure. No 10-36.

At one point, some officers noted that Suiter’s “radio and weapon” were left behind. One officer located them “back there where he got hit.” Bomenka could have left the gun and radio behind to preserve the crime scene. In that case, someone probably stayed behind to guard it, maybe the officer who knew where Suiter “got hit.”

In other words, either Bomenka left the gun unattended or someone on the scene at this point had interacted with him. Yet, nobody could say if the shots came from the ground or a window. Later, Bomenka told investigators that the shooter must have fled from the back of the alley.

Accident – about 4:41pm to 4:42pm

The patrol car carrying Suiter got into an accident about a mile south of Bennett Place with a UM police car that was trying to help clear a path for him. “I don’t know which way they’re coming,” the dispatcher announced just before. The accident also involved a black car, an SUV, and some pedestrians. It’s unclear exactly when the accident happens. An ambulance identifies itself at that intersection at 4:41pm; by 4:43pm, choppers were being called to the scene.

Bomenka’s vehicle made a left turn from Martin Luther King, Jr Blvd onto West Baltimore St., where it must have run into the front of the black car. Someone on the radio described trauma to the “left outside door” of the patrol car, as shown by a news report at the time.

Overall, Bomenka’s radio silence led to safety issues at both locations. He didn’t have his radio on him, but at least one patrol officer arrived with a radio and the car that transported Suiter to the hospital. Officers also have direct phone numbers for dispatchers. Someone was able to call in that he was headed to the hospital, just not in which direction. It’s never been made clear if someone was in the car with Bomenka and Suiter. It’s another conspicuous hole in the story.

All of these issues were reviewed by Seth Stoughton, law professor at the University of South Carolina, former police officer, and policing expert. He learned that Bomenka didn’t have his radio on him; didn’t provide any information on the ground or the radio; may not have provided his identity; took Suiter from the scene, leaving the gun; and got into an accident. The story gave Stoughton pause: “I can understand extreme panic leading to a series of isolated missteps,” he said. “But Murphy’s law aside, it’s not the case that everything can go wrong would go wrong. I would expect something to go right.”

UPDATES (September 2018):

In August, an Independent Review Board released a report following a months-long investigation into Suiter’s case. BPD released audio and video evidence at the same time. Interestingly, both leave out much of the information above gathered from dispatch calls. There are no details provided about the 911 call, the UM call, or the multi-car accident. The video from the convenience store is not included.

However, the report and evidence do provide some clarification on some of the details above. For one, Suiter’s gun and radio cannot be seen clearly on video in his hands, heading into the lot. Anonymous police sources fed this misleading information to the Baltimore Sun.

Another surprising revelation is that Bomenka did not join Suiter on the trip to the hospital. Rather, he stayed behind on the scene and, as indicated by dispatch, was not able to provide any information at all. Later, he offered a comprehensive narrative to investigators.

Finally, audio was released of Suiter’s reported last call. It does sound like possible “distress” followed by one rather loud gunshot, though not in the “background” as Davis described.The audio from the earlier Signal 13 that was sent to a local Pennsylvania TV station remains a mystery.

Amelia McDonell-Parry contributed to this story.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.