Part 1: The Commissioner and his Story

This multi-article series revisits the available evidence and reporting around the shooting death of Homicide Detective Sean Suiter on November 15, 2017, adding analysis and some new information to the conversation so far. This information is provided in advance of the findings of an independent panel, commissioned by the department, that has promised insights and recommendations.

This first article looks at the trajectory of Commissioner Kevin Davis in his handling of this case in media and similar cases in the past. Part 2 deconstructs the reported timeline of events, comparing it to police audio records. Part 3 considers the ballistics discoveries and evidence. Part 4 looks at the emergence of the suicide and other theories, as well as the role of the federal government. The Addendum looks at the video evidence, released with the findings from an Independent Review Board. The Conclusion enhances the audio and video further and arrives at a homicide conclusion.

“Increasingly uncomfortable”

It had been one week since Baltimore Homicide Detective Sean Suiter was shot to death in the head in a vacant lot in West Baltimore while on duty. Commissioner Kevin Davis stood before his regular audience of local reporters, continuing to push a narrative that was slipping rapidly away from his control: Suiter was shot by a “suspicious” stranger, he said, identified initially as a “black male,” in a “spontaneous” interaction. The Baltimore Police Department (BPD) had locked down six blocks in the Harlem Park neighborhood for five days while searching the area for the killer, with no strong suspects emerging.

This was the fifth press conference the commissioner would hold within one week on Suiter. Historically, Davis focused a lot of energy on media engagement. He gave frequent statements to the press. He developed relationships with key reporters, making eye contact and repeating their name when answering questions.

Suiter’s death would challenge Davis’ media savviness. In one week, the case had taken more narrative twists than an episode of Law and Order. The detective was determined to have been shot by his own weapon, but the autopsy concluded that his death was a homicide. Suiter’s gun had been taken away from him by the shooter and used to kill him, Davis said, and the detective made a “brief radio transmission” of his last seconds. Also, Suiter’s body had been driven away from the crime scene towards the nearby hospital and gotten into an accident.

Then, there was the mother-of-all-twists, one week after Suiter’s shooting:

“I am now aware of Detective Suiter’s pending federal grand jury testimony surrounding an incident that occurred several years ago with BPD officers who were federally indicted.” Davis said. “The very next day after Suiter was murdered, he was scheduled to appear before a federal grand jury “in a “GTTF” case.”

“GTTF” was the Gun Trace Task Force, an elite squad that was functioning as a criminal enterprise, stealing from and brutalizing civilians while receiving acclaim for its drug and gun seizures. Suiter’s imminent testimony suggested that there may be more to the story of his death. A “black male” possibly being blamed for the actions of dirty cops touched a familiar raw nerve in Baltimore.

Davis dropped this bomb on the evening the before Thanksgiving, probably hoping it would diffuse over the long holiday. WBAL’s David Collins asked the relevant question: “Doesn’t it seem awfully coincidental that he was going to testify?” Davis responded, “It certainly makes for great theater,” but denied evidence of any link.

Then, on November 30th, the federal government unsealed the indictment in the case for which Suiter was set to testify. The next day, Davis shared a letter he wrote to the FBI, asking them to take over the Suiter investigation. He wrote that he was “increasingly uncomfortable” that his homicide detectives might be missing information.

“Yesterday’s indictment revelation was an example of finding out information that I just didn’t know before,” he told reporters. In a rare public statement later that night, U.S. Attorney Stephen Schilling called Davis “mistaken.” In fact, the feds had told him about the indictment the day after Suiter was shot. In other words, Davis could’ve just told his detectives about it.

By this point, Davis’ story had officially unravelled from any logical core. His demeanor grew less confident too. His answers grew longer and more rambling, as if by continuing to talk he could convince a skeptical audience.

“Very, very, quickly”

There is one reading of Davis’ behavior over the seven increasingly “uncomfortable” press conferences on Suiter’s death in which he made some early mistakes and spent the next two months covering his own tracks by doubling down on his theories.

One example of this appeared on November 30th, in an unusual story in the Baltimore Sun. It was about a man who allegedly took a gun from a cop and shot the cop in the hand. It included especially graphic body camera footage. Davis was the only source quoted by the reporter, Kevin Rector:

“These things happen very, very quickly. It’s a matter of seconds. It’s a violent struggle. And thank God we’re not talking about planning another police funeral.” This article came out just as the pressure in the Suiter case was peaking. Davis’ language here was startlingly like the language he had used to describe Suiter’s killing:

“We have physical evidence of a struggle,” he had said of Suiter, “Obviously it occurred very, very quickly, in a matter of seconds.”

Another layer here is that the body camera footage does not clearly show an officer being shot in the hand by the suspect. The footage shows a cop poking his gun around the suspect’s waistband, alarmingly close to his hands. They then wrestle to the ground, obstructing the camera’s view, and a gun goes off, but it’s not clear how or by whom. The man is then tasered. The officer cries out that his hand is “broken,” not shot.

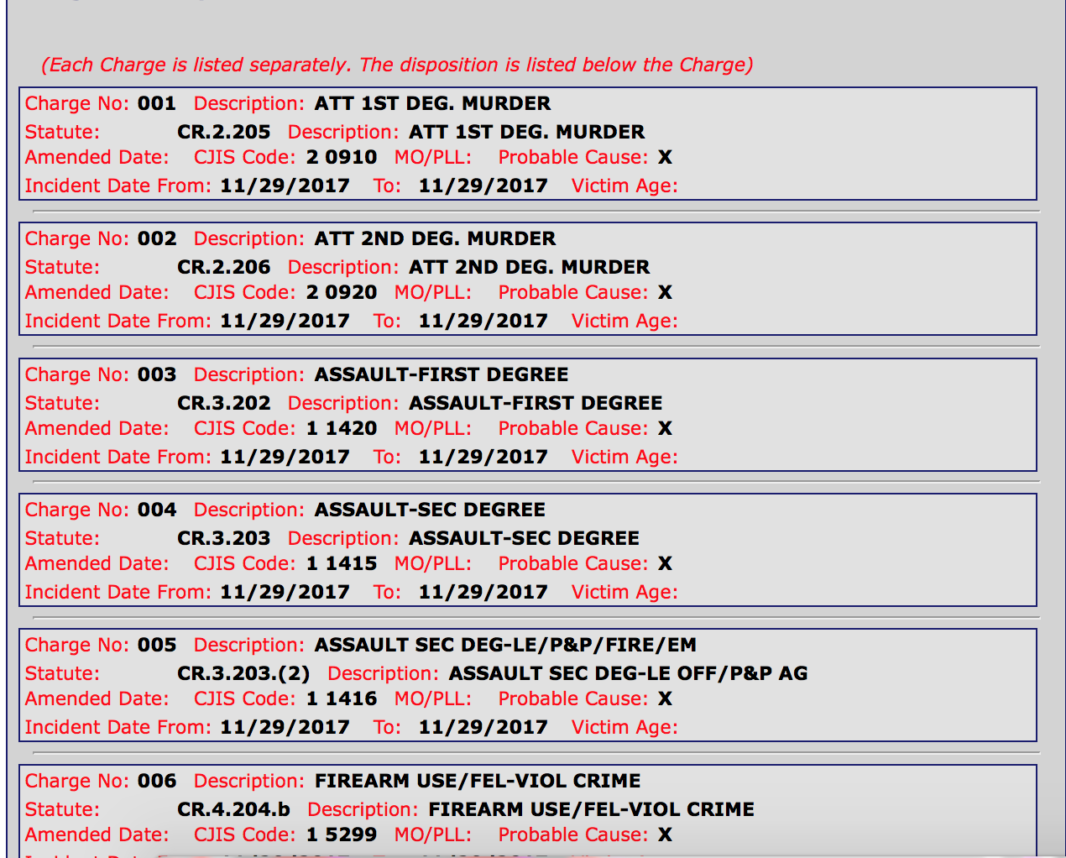

This man was arrested on a long list of charges, up to attempted murder. The charges were reduced to first-degree assault and possession when the case was transferred to Circuit Court. I reached out to BPD and Rector for comment on this story; they did not respond. The man’s attorney, Jerry Tarud, would only say, “That is not what I see on the video,” in regards to Davis’ statement.

So, at best, Davis was exploiting this unrelated case to make his point – that cops do get their guns taken away from them and are shot “in seconds.” The “at worst” on this case is very dark, if we consider the legacy of some BPD officers staging videos to frame suspects.

Rapid Misinformation

Commissioner Davis didn’t always have such a hard time controlling media narratives as he did with the Suiter case. In 2015, as Deputy Commissioner, he oversaw a two-week “task force” investigation into the death of Freddie Gray. Files released in 2017 show that members of the task force contributed to misleading leaks around Gray’s case. In the week leading up to the May 1st filing of charges against the officers by State’s Attorney Marilyn Mosby, media reported all of the following as possible causes of Gray’s death: He was killed from banging his own head against the van wall, from hitting his head against a bolt in the van, from a pre-existing back condition, from a drug overdose, and more. None of these theories were introduced by the officers’ defense teams in court. They could all be disproven by the facts available.

Many of these stories were shared by credible outlets, like the Washington Post, and went viral. They were reported as substantiated by anonymous police investigators and documents. The bolt story, for instance, emerged from private meetings between investigators and the Medical Examiner, during which she stated that the bolt in the van did not cause Gray’s fatal injury. But only insiders would have known about the bolt at all.

There was little to no media pushback against any of these stories in 2015 or the whole campaign of rapid misinformation, besides one small correction in the Post. Reporters did not press police commanders to affirm or deny the stories, creating a bizarre disconnect between official and anonymously leaked accounts.

Was Davis personally involved in any of these leaks? That bolt story, for one, was first leaked to a local Washington, D.C. television news reporter. It would’ve seemed strange – unprecedented, even – for a Baltimore story to break in another local outlet, except that Kevin Davis had given statements to that reporter for years as Deputy Chief in Prince George’s County. (The fake leaks were often sent out of town.)

While all of this was happening behind the scenes, in 2015, Davis was filmed for a HBO documentary listening thoughtfully to the community around the uprising.

He was portrayed in a four-part Baltimore Sun series on the Freddie Gray task force as a strong, ethical leader. That series included highly produced videos of the investigators at work. One video showed an investigator breaking into the locker of the van driver, Caesar Goodson, with a warrant and shaking his head in judgement at the contents. There was nothing discovered of any concern in Goodson’s locker; some investigators sought to focus the guilt around the driver.

All of this was just the tip of a very messy iceberg when it came to media manipulation around Freddie Gray’s death, as I have reported elsewhere. If it sounds overly confusing, that was the point. Some of these patterns repeated in the Suiter case.

The Freddie Gray case cost then-Commissioner Anthony Batts his job. It won Davis a promotion. The new Commissioner positioned himself as a corrective to the problems Batts had introduced, and the local media responded in a mostly positive light. Over the next two years, Davis personally survived scandals that might have brought down a less media-savvy police leader, from the GTTF indictments to some of his officers being caught re-staging evidence discovery on body cameras.

Given this history, it is no wonder that Davis may have felt like he could pull off controlling the narrative around Detective Suiter’s death, one that involved another complicated mystery. It had worked for him in the past. The big difference was that, this time, there were many officers within the department that opposed Davis’ agenda, for differing reasons. One of their best and brightest was killed this time, a husband and father of five. And this time, the local media also pushed back, but largely in one direction – towards the theory that Suiter ended his own life.

“Making strides”

Davis was finally fired in mid-January of this year. Mayor Catherine Pugh claimed that she was “impatient” with rising crime numbers but those crime numbers were nearing their third year, during which time she had remained loyal to him. Ironically, Davis’ firing directly paralleled that of Batts. Both leaders bungled high-profile death investigations; both received severance payouts.

Before his firing, Davis wrote an op-ed about his last year in Baltimore policing, entitled “BPD Making Strides.” His article made every verbose effort to highlight his positive achievements. In reality, 2017 was framed by the GTTF indictments in March and Suiter’s death in November, with record-breaking homicides. The Baltimore Sun published his op-ed, but on a Saturday morning, just before New Year’s Eve. In another ironic twist, the media finally gave Davis his own pre-holiday dump.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.