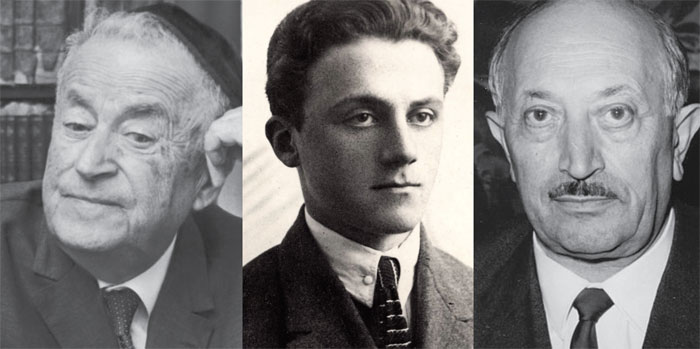

From left to right: S.Y. Agnon Pictorial Parade/Hulton Archive/Getty Images / Emanuel Ringelblum / Simon Wiesenthal

Keystone/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

From left to right: S.Y. Agnon Pictorial Parade/Hulton Archive/Getty Images / Emanuel Ringelblum / Simon Wiesenthal

Keystone/Hulton Archive/Getty Images “This is the chronicle of the city of Buczacz,” wrote S.Y. Agnon in his introduction to “A City in Its Fullness,” a book of stories about his birthplace and childhood hometown. “I have written this in my pain and anguish, so that our descendants should know that our city was full of Torah, wisdom, love, piety, life, grace, kindness and charity, from the time of its founding until the arrival of the reviled degenerate with his impure and deranged accomplices who wrought destruction upon it.”

As the world gazes upon the ugly images of war in Ukraine, the colorful maps on the television screens do not show one small town in Western Ukraine, along the Strypa River. Buczacz – which was once the home to an illustrious Jewish community until they were massacred by the Nazis in 1943 – is the birthplace of three towering Jewish personalities from the 20th century:

S.Y. Agnon (born 1888), the writer who was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1966; Emanuel Ringelblum (born 1900), the historian and archivist of the “Oyneg Shabes” archives from the Warsaw Ghetto; and Simon Wiesenthal (born 1908), the Nazi hunter who dedicated his life to bringing fugitive Nazi war criminals to justice.

One small Ukranian town, three Jewish boys, three roads diverged, three destinies.

The eldest of the three, Agnon was the literary architect of memory. Originally named Shmuel Yosef Halevi Czaczkes, he emigrated to Palestine in 1908, where he published his first story and took his pen name “S.Y. Agnon.” He left Buczacz at the age of twenty, but it never left him.

From his earliest writings all the way to his “chronicle of the city of Buczacz,” Agnon wrote with the shadow of Buczacz hovering over him. His post-Holocaust stories about Buczacz were written as a chronicle of memories from his study in Jerusalem, filled with longing and nostalgia for the Buczacz that was no more. When asked about the book of Buczacz he was working on, Agnon responded “I am building a city.”

But before waxing nostalgic on Buczacz in the 1950’s and 1960’s, Agnon visited his birthplace one more time in 1930. That seven-day visit inspired his famous novel “A Guest for the Night,” where his portrayal of Buczacz was one of darkness and doomsday. He renames the city Szibucz (which means “confusion” in Hebrew – a literary play on Buczacz) and the story opens on Yom Kippur and ends on Tisha b’Av. From the fast day of introspection to the fast day of destruction, a total of eleven months elapses, the same amount of time a mourner recites Kaddish for a deceased parent. “A Guest for the Night” seemed to eerily foresee the Holocaust, and its publication date – September 1939 – coincided with the Nazi invasion of Poland.

Emanuel Ringelblum – Agnon’s younger cousin – was the chronicler of catastrophe. In one of his Buczacz stories – “The Partners” – Agnon makes mention of “a relative of ours” from his mother’s side, a brilliant boy named Monyo. “This was Menahem Emanuel, who was Emanuel Ringelblum, murdered by the filthy, accursed agents of the wretched abomination, in the Warsaw Ghetto.”

The story of Ringelblum’s famous “Oyneg Shabes” archives from the Warsaw Ghetto was brilliantly chronicled by historian Samuel D. Kassow in “Who Will Write our History” (a film by the same name was produced by Nancy Spielberg). Like his cousin from Buczacz, Ringelblum understood the enduring power of the pen, but his “study” lacked the safety and comfort of Agnon’s in Jerusalem. Under the squalid conditions in the Warsaw ghetto, Ringelblum mobilized writers, artists, poets, rabbis and intellectuals, encouraging them to write and tell the stories of what was happening to the Jews in the ghetto. The result of Ringelblum’s secret literary society under Nazi persecution was the largest cache of documents – some 35,000 pages – of eyewitness Holocaust testimonies.

Ringelblum’s heroic act of cultural resistance rivaled the more famous physical resistance of the Warsaw Ghetto. In the words of Samuel Kassow, “theirs was a battle for memory, and their weapons were pen and paper.” Ringelblum was murdered by the Nazis, but like his cousin Agnon, this “boy from Buczacz” made sure that the Germans would not have the last word.

The pen, indeed, outlasted the sword.

The youngest of the three, Simon Wiesenthal was the hunter of justice. Born in Buczacz the same year Agnon left the city (1908), Wiesenthal became the post-Holocaust voice of bringing Nazis to trial. A survivor of several concentration camps, Wiesenthal took it upon himself to track down Nazi war criminals around the world. Growing up, I had never heard of Agnon or Ringelblum, but I read Wiesenthal’s “The Murderers Amongst Us” and was inspired by his quest for justice against evil. When I was privileged to meet him in high school, I felt like I was in the presence of a larger than life righteous human being. He was one of my heroes, and still is.

Also a writer, Wiesenthal wrote “The Sunflower: On the Possibilities and Limits of Forgiveness.” Probing the moral dilemma of “what would you do if a dying Nazi soldier asks for your forgiveness” while you are imprisoned in a concentration camp, the same man who spent his post-WWII life hunting Nazis gave us a reflective piece of literature that is now a classic in Holocaust and religion studies.

Three brilliant Jewish boys, three roads diverged, three destinies, but one common legacy: to creatively preserve the memories, stories, values and ideals of the Jewish people.

One small Ukranian town, three brilliant Jewish boys, three roads diverged, three destinies, but one common legacy: to creatively preserve the memories, stories, values and ideals of the Jewish people.

Buczacz – small in size, giant in genius.

Rabbi Daniel Bouskila is the Director of the Sephardic Educational Center and the rabbi of the Westwood Village Synagogue. His monthly column on Agnon appears on the first Thursday of the month.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.