There seems to be a geographical determinant in literature. The New York novel concerns the individual (searching for himself), his associate/antagonist in the quest, the City itself.

The hero in the Chicago novel is searching for a living. His and her task is less effete. The city here is neither friend nor foe, but neutral — it is an environment whose savagery may and must be overcome, whose lawlessness is not that of the impersonal/established, but of the Frontier. It is a mechanism getting, spending, inventing and destroying, and neither the city nor its heroes have time for “self.”

(“The Great Gatsby” is an effete work, schoolchildren are taught to consider it as such, and write about the symbolism of the light at the end of the pier. Dreiser’s “The Financier” is a trilogy about Street Traction.)

New York was settled in the 17th century, Chicago in 1835. And it seems Los Angeles has never been settled at all.

New York’s lifeblood has always been trade, between established locations: with Europe, and the Eastern Seaboard.

Chicago, which Mencken called the first non-European city in America, grew as the Factor/Merchant to the West — the magnificently situated interchange between the Great Lakes and the Mississippi River, and the Frontier. Who had the time there, or the inclination, to consider “self”? Only the effete, writing for the Little Magazines and so forgettably aping the New York (and, thus, the European) mode.

Now see Los Angeles, a coastal wasteland between the barren desert and the salt sea.

Its literature begins with Dana’s “Two Years Before the Mast” (1840), a sailor’s account of California coasting, shipping and trading, and the vicissitudes of that lifeless coast. The literature recommences with the novels of the 1920s and the infecundities of the motion picture business.

What is the nature of the land, as Moses asked his spies going to Canaan: Is it good or bad, fruitful or barren? The nature of Los Angeles is this: It is a desert.

Its first wealth came from petroleum, that good desert crop. It is most famous as the Mother of Movies, which are enjoyed in the dark.

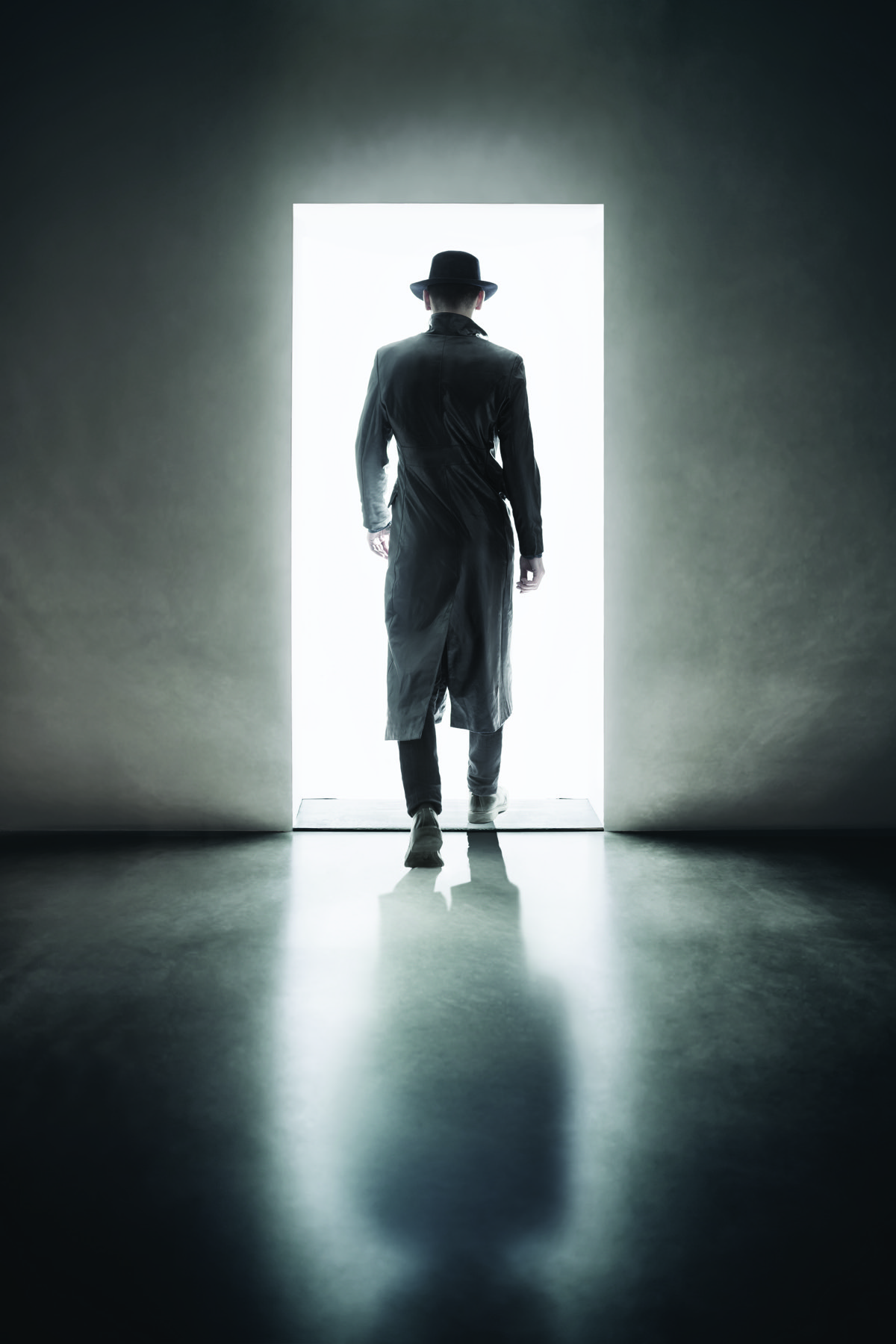

As is everything in The Desert: The daylight, for the desert creatures, scorpions, lizards, or movie producers, is to be endured. Life truly begins when the sun sets.

The true literature of Los Angeles is a record of commerce with and in the dark. It is the detective novel and, particularly, the Noir. The literature of Los Angeles is pulp fiction.

The denizens of this desert-at-night are concerned neither with finding the “self,” nor with making a living in a difficult world; they want to kill their spouse for the insurance.

The L.A. Noir is not a struggle between Good and Evil, it is one in which Good has not even been entered.

The nominal heroes of these pulps are — however interestingly written — flags of convenience. What do the Continental Op or Philip Marlowe actually want? To find a killer, of course; but why? They may have personality but, finally, it derives flavor rather than substance.

Consider the Bible as Literature.

There are these miscreants living on the frontier. There is no one who is on the up and up. We have liars, thieves, adulterers, murderers, the near-infanticidists, the incestuous, the cheaters and the cheated; things which cannot possibly get worse get worse continually; and the whole damn place comes under the influence of the Oppressor (the Cattle Baron, the Outlaw King, the Black Hat — here called Pharaoh).

A hero arises. He is asked to Clean Up the Town (see “The Magnificent Seven,” “The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance,” “Blazing Saddles”). This is the staple of the Frontier Myth: the reluctant hero.

But with the Exodus from Egypt, the desert narrative changes from the Frontier Novel to the Noir.

Now the desert story is not sheepherders against cattlemen, the Sown against the Wild (the Bible story prior to Moses), now we enjoy the tale of a unitary, though corrupt, entity (L.A., or in this case, the Jews), and its pressed-into-service Sheriff.

Philip Marlowe wants to keep his feet up on the desk and drink. Moses wants to herd sheep. The P.I. is drawn into the hunt by the beautiful or pathetic dame, Moses by God, and they both go among charges trying to instill a bit of order. These arbiters of the Desert Loathsomeness are, finally, a writer’s convenience. Remove the P.I. and we have the truer version of Los Angeles, the Noir tout entiére of the pulps (Horace McCoy, not Raymond Chandler). There is a good historical precedent for these novels of desert perfidy, and their reluctant Sheriff: It is the Bible.

Both sets of desert dwellers lie to them, plot against them, and try to get away with murder.

Episode by episode, in the Noir and in the Chumash, a bit of truth is revealed, and the particular upheaval is quelled. It will break out again in the next novel and in the next parashah. At the end of each sequence the hero, essentially a catalyst, returns to his desk or his tent sadder but no wiser than before: It’s the Jews, or it’s Chinatown, and there you have it.

What is Moses’s objective? The same as that of Philip Marlowe or Sam Spade: to do the dirty job he was assigned as honorably as possible. What is his reward? That’s his reward.

The P.I. goes back to get drunk, and Moses (like every movie cop who’s trying to do some good) gets fired for subordination.

For there is no good in the desert. The sun goes down and all the crawling things emerge and try to eat each other.

The novel’s nature, it seems, is determined by the nature of the writer’s geographic situation. Proust is trying to recapture memory in the taste of a cookie. The influence of Civilization (consider it effete or magnificent) lessens on its Westward way until, fetched up in Los Angeles, we find again the saga of savages caught between the desert and the salt sea, their blinded confusion by day, and their dark deeds at night — the stories of the Bible come again. © 2018 by D. Mamet

David Mamet is an award-winning author and playwright.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.