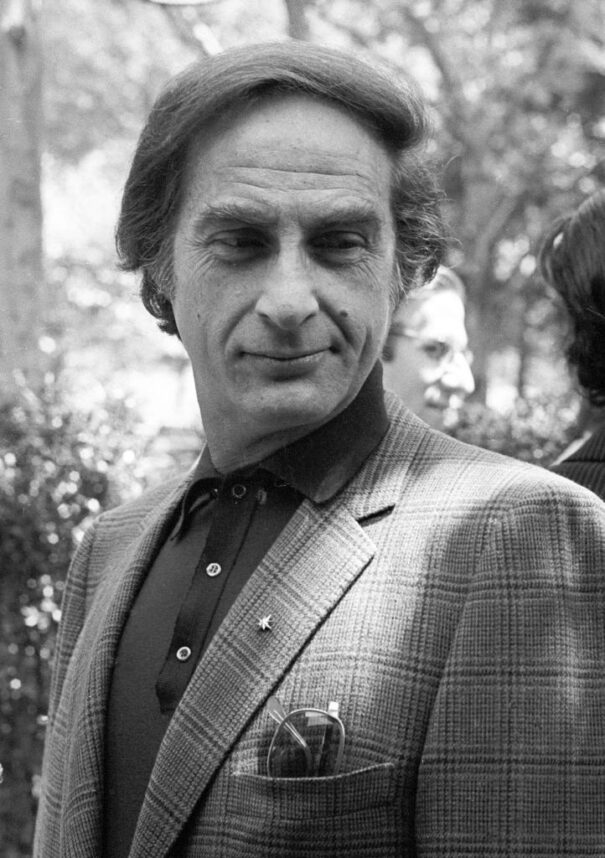

“For me,” said Pablo Picasso, “there are only two kinds of women: goddesses and doormats.”

Picasso was somewhat of an expert on women: He knew how to destroy them. Of the seven most important women in his life, two killed themselves and two went mad.

I thought of this quote when reading about how Linda Sarsour allegedly dealt with sexual assault accusations at the Arab American Association of New York, where she was executive director. According to The Daily Caller, in 2009 Asmi Fathelbab told Sarsour that she was being repeatedly sexually assaulted by volunteer Majid Seif.

“Sarsour is no champion of women,” said Fathelbab, 37. “She is an abuser of them.” Sarsour, she said, told her that “something like this didn’t happen to women who looked like me. … She told me I’d never work in New York City again for as long as she lived.”

Others have come forth to corroborate Fathelbab’s allegations. A New York political operative said that Sarsour was “militant against other women. … The only women [Sarsour] is for is herself.” Sarsour denies the allegations, portraying herself, as always, as the real victim.

None of this is shocking to anyone who has followed Sarsour’s hate-filled rhetoric, and while the allegations remain allegations, much of the mainstream media — notably The New York Times — are curiously silent about this #MeToo case after creating hysteria about every other one.

Nevertheless, I imagine the story also doesn’t come as a shock to most women, who have no doubt been treated like doormats by ambitious women like Sarsour at one time or another. It’s the abuse no one likes to talk about.

Of course, anyone who has ever been around young girls knows how cruel they can be to one another.

But everyone expects that most girls will, well, grow up.

That’s not always the case. Consider, for instance, women in the office who take out their unhappiness on other women. An editor at a book publisher that I used to work for would scream at me each morning from Paris, calling me the nastiest names. I used to joke that it was like the old “Saturday Night Live” routine: “Jane, you ignorant slut.” It didn’t really bother me because I knew I was doing good work, and I knew that she was in a difficult marriage. Neither of which, of course, made it OK.

I’ve had other instances of female abuse in the workplace, most of which have come when I knew the woman personally. This has led me to two conclusions about female abuse: One, many women do it because they can — because they see other women as soft targets. Two, many women do it because they feel threatened by other women’s success.

There is a popular meme on Facebook: You can tell who the strong women are—they are the ones who support the success of other women.

You can tell who the strong women are — they are the ones who support the success of other women.

I don’t expect other women to treat me a like a goddess (men, on the other hand, absolutely). But I do expect a level of respect that some women seem incapable of providing. The “sisterhood” model, as appealing as it sounds, breaks down when it assumes that all women think alike, which, of course we don’t.

But respect is most needed when we don’t think alike. I respect you even if we have different political views. I support your career, and if anyone — male or female — is bullying you, I will be the first to call it out.

As for the allegations against Sarsour, they are especially egregious because they involve both sexual assault and serious damage to a woman’s career. It will be interesting to see how this plays out. Women who support Sarsour’s politics are being put in a challenging position: Which do they care about most, the fact that Fathelbab allegedly was sexually harassed, and then bullied by Sarsour, or the fact that they can’t call out a “sister”?

Here’s hoping that Sarsour’s supporters don’t turn into female Picassos for all of the wrong reasons.

Karen Lehrman Bloch is a cultural critic and author.