After a night of tossing and turning, I finally gave up on sleeping at 11 a.m. Sunday morning. I rolled over, checked my phone and logged into social media.

Everyone will have his or her “where were you on the bleakest morning in recent Los Angeles memory?” moment. Mine began the way many of my mornings do: with the grim expectancy that something awful awaited me.

Still, when I received a text message from my good friend — a fellow Clippers fan — that read: “Holy [expletive] Kobe,” it didn’t occur to me that he might be dead. Kobe Bryant had long ago ceased being mortal; ceased being a celebrity basketball player or even a washed-up dad. The concept of his death was as easy to grasp as outer space. And yet it was out there.

I’m a breaking news reporter for The New York Times, so before I could process any of these thoughts, I threw together some things — my laptop, a granola bar, a banana, an orange, leftover pasta, a loaf of bread — and raced to the helicopter crash site in Calabasas. I had sports talk radio on to catch any updates, and the host was audibly fighting back tears. Oh, and my tefillin. I brought my tefillin, too.

Kobe and Shaquille O’Neal were why I fell in love with basketball, but it was Kobe’s moves — his fadeaways, his reverse layups — that I rehearsed in the backyard. His work ethic was the stuff of legend. There are countless stories about players eager to impress Kobe showing up to practice at 6 in the morning, only to find Kobe in a full sweat. He only had one speed: full tilt, and didn’t have much energy for Sunday drivers. His exacting, unforgiving nature often alienated his teammates. His selfishness on the court made him eminently hateable to fans. He didn’t mind.

There was something about his devotion to the game that resembled the kind of fervent commitment we aspire to in our own faith — a constant, relentless, undeniable devotion to the values and commandments we hold close.

I was still rooting for the Lakers, still very much idolizing Kobe, when I came home from a babysitting gig in 2003 and saw my mom with a stoic look on her face. She told me that Kobe had been accused of rape. I broke down crying. How was it possible that someone larger than life, an iconic perfectionist, my hero, could do something like that?

He was never truly held accountable for what happened in Colorado. Not in the courts, the press or among NBA fans, who adored him to the day he died. But I eventually came to recognize his behavior as a slow redemption of mistakes he made when he was younger. He was a full-throated supporter of women’s basketball: as a WNBA fan who frequently promoted its stars as his peers, as a dad teaching the game to his daughter, and as a coach of her youth team. He applied his Mamba mentality to making good on the giant mistake of his public life.

Is Kobe’s death a loss to the Los Angeles Jewish community? Absolutely. He was the only subject Jews in this town agreed on. I will add, that people who have voiced their dismay with Bryant’s past have often been brutally harassed by his fans. That includes members of our community, and it is up to our leaders to condemn those actions. Even the basketball fans who hated Kobe at least respected that he was only ever being Kobe, and never anyone else. There was something about his devotion to the game that resembled the kind of fervent commitment we aspire to in our own faith — a constant, relentless, undeniable devotion to the values and commandments we hold close.

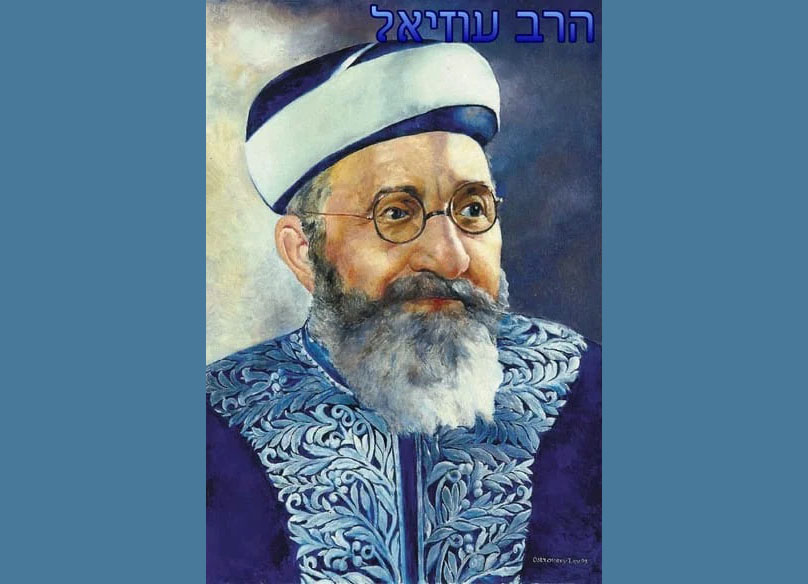

I brought my tefillin to Calabasas because several months ago, I decided to start laying tefillin every day. Because I work from home and more or less make my own schedule, it was a practical goal.

I brought my tefillin to Calabasas because several months ago, I decided to start laying tefillin every day. Because I work from home and more or less make my own schedule, it was a practical goal. I didn’t tell anyone I was doing it, and I didn’t know the various schedule flukes and breaking news stories that would make it hard from time to time.

Below the scene of the helicopter crash, where hundreds of people had gathered to pay their respects, one person told me that Kobe was “an example of what every single person is capable of if you don’t let fear get in the way.” I remembered my tefillin. When the day’s reporting was done, there was about an hour until sunset. Not wanting to pull over on the freeway, I weaved through traffic all the way home. I got there with enough time to wrap tefillin and say Ashrei, too. I certainly needed it.

Louis Keene is a writer who lives and hoops in Los Angeles. He tweets at @thislouis.