Alexi J. Rosenfeld/Getty Images

Alexi J. Rosenfeld/Getty Images October 7, whose long-term consequences will become clear in the years to come, opened up an opportunity for Israeli society: a window through which it is possible to return to a state of greater cohesion. You probably remember the first weeks of the war. The quick mobilization, the urge to volunteer, the recognition that Israel must change, the abandonment of the divisive discourse. In his new book The Eighth Day, Israeli philosopher Micah Goodman returns to those days, and tries to derive from what happened a few lessons for a better future. As part of the research for the book, a survey was conducted. Its purpose was to try to find what Goodman calls the “zone of agreement.”

Goodman deals extensively with the zone of agreement. And he clarifies as follows: “One must distinguish between zone of agreement and agreement. Agreement is a situation where two or more people have the same opinion; In a zone of agreement there are people who do not necessarily have the same opinion, but their difference of opinion is small enough for them to be able to close it through conversation, listening and compromise.”

In the survey we tried different means to locate this “zone” and define its boundaries. One of them was to look at the motivation of people to have unity in Israel. Who wants unity? That’s an easy question: everyone wants unity. Costless unity is like “world peace.” Is there anyone who does not want world peace? Everyone wants it — on their own terms. The problem with world peace is not a problem with the principle, it is a problem with the details. Russia wants world peace without an independent Ukraine; Ukraine wants world peace without Russian patronage. This is one of many reasons why world peace is a noble but unattainable aspiration.

It’s easy to like unity in principle, it’s harder to like it when it’s weighed against a price.

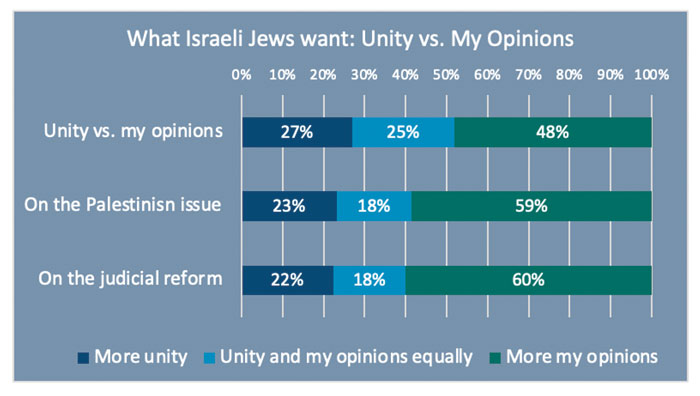

Like world peace, so is Israeli unity. It’s easy to like it in principle, it’s harder to like it when it’s weighed against a price. And here is a way to identify this difficulty. In the survey we did not ask about unity as a general matter, but about unity in the face of its possible cost. What is the possible cost of unity? To have unity, each one of us has to give up something. To compromise. Unity will require compromises on charged issues, such as the policy regarding the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, or the powers of the Israeli justice system.

So we presented a scale and asked as follows: “The upper part of the scale symbolizes your positions. The lower part of the scale symbolizes the unity of the society. Please try to place the marker on the place that, in your eyes, is the right balance between your desire for the policy to be the way you want it, and your desire for unity in Israeli society.

This is the real choice: not whether we want unity, but whether we are willing to give up a little for the sake of unity. Well then, what do Jewish Israelis want? It turns out that the public has a slight preference for their positions over unity. But there are two groups that lean towards unity, and are ready to compromise their positions: those who define themselves as “moderate right” and those who define themselves as “center.” Ask: What is the size of these groups out of the entire Jewish society in Israel? The answer: Nearly half defined themselves this way in our survey. Sixty-four percent of those self-defined as “moderate right” placed their marker on the unity/me scale towards unity. Sixty-two percent of those self-defined as “center” placed themselves on the unity/me scale in the direction of unity.

But it doesn’t end here. Because after we asked generally about unity vs. my opinions, we continued to ask about two specific issues. We asked about the issue that split Israel before October 7, and the one that may split it in after October 7.

We asked: What is the right balance between the need for unity and your opinion on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. We asked: What is the right balance between the need for unity and your opinion on matters related to Israel’s judicial system?

Two things happened when we moved from the general dilemma to the focused dilemmas. First, for all the respondents, the tendency to prioritize unity decreased. Second – it was possible to identify the difference between the “moderate right,” for whom it is more difficult to give up on their opinions on the Palestinian issue, and the “center,” for whom it is more difficult to compromise on the legal reform issue. In fact: only the “center” bends towards unity in the Palestinian context, and only the “moderate right” bends towards unity in the context of the judicial system.

You want to draw a pessimistic conclusion from this data? It is certainly possible: Israelis want unity only in theory, not in real life. Or – you can read Micah Goodman, and look at the data, and understand that unity and cohesion will not emerge by itself. It is a challenge that needs to be worked on. And Israel has no other choice.

Something I wrote in Hebrew

Regular readers of this column know that Prof. Camil Fuchs, a well known and distinguished Israeli statistician and pollster, was my friend and my partner. We wrote a book together, we started a research initiative together. Prof. Fuchs died last week at 78. Here’s a paragraph I wrote about him:

I once asked him what he thought the pollster’s role was in a democratic society. He looked at me, as if bewildered at the very question. Then he said: to provide information. We are providers of information. And it should be reliable. If the information is useful to someone in making decisions, what to support, who to vote for, how to think about policy – we have fulfilled our role. But it must be reliable, he repeated. Fuchs was straight as a ruler. Sometimes straight to the point of boredom. I once wrote: “Last Thursday we asked 100 Meretz voters who they support.” Fuchs sent a comment: “There were only 99 respondents.”

Can’t we round up? No, we can’t!

A week’s numbers

Read the column above to understand how this was done and what it means:

A reader’s response:

Amy Dobrinsky wrote: “I don’t think Israelis understand how badly their country is portrayed these days.” My response: Some do, and they are worried about it. We’d have to wait and see if this is a passing wave of negativity, or a new image that is going to stick.

Shmuel Rosner is senior political editor. For more analysis of Israeli and international politics, visit Rosner’s Domain at jewishjournal.com/rosnersdomain.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.