Yair Lapid

Amir Levy/Getty Images

Yair Lapid

Amir Levy/Getty Images Yair Lapid, a former Prime Minister and the head of the Israeli opposition, has a new slogan: “the 75 alliance,” also called “the new Israeli alliance.” Lapid keeps repeating this phrase, so it is clear that this is a deliberate, conscious move. It is also an important, interesting, move. Lapid makes a simple basic claim: There is a large Israeli group that can agree on Israel’s main vision, and hence form a majority that could govern the country with less friction and more harmony. Who belongs to this alliance? To answer this question, we need to consider a slight and important rhetorical change Lapid has made.

Two weeks ago, Lapid explained: “In the 75th year of the state, 75% of the citizens of Israel agree on 75% of the issues … 75% are nationalist-liberals.”

Two weeks ago, Lapid explained: “In the 75th year of the state, 75% of the citizens of Israel agree on 75% of the issues… 75% are nationalist-liberals.”

But last week he spoke about “a new Israeli alliance … I call it the 75 alliance”.

The difference is subtle, and yet important. In the original presentation, Lapid was speaking about 75%. In the representation about 75 … what? It seems that now Lapid is speaking not about percentages but rather about seats in the Knesset. 75 seats in a 120 seat Knesset means 63%, not 75.

It’s a big difference. Because while a 75% alliance is not realistic, a 63% alliance is a little less far-fetched. It won’t be easy to get the consent of 63% of the public on all issues, but there are important things that could get such a majority. Here are some examples. Most of the public, approaching Lapid’s 63%, does not think that there will be a peace agreement with the Palestinians in the next decade. A large majority agrees that the rights of the Arab minority deserve protection. A large majority agrees that the law should not be taken into one’s own hands.

So, is there an alliance of 75? It is still far from certain, but it is a possibility that deserves to be examined. Lapid is careful to call it “liberal-nationalist.” So it is mostly Jewish, and not too rightwing. Still, identifying a group of more than 60% who will agree on most issues, and above all, who will agree sufficiently to prevent severe friction, is not a simple matter. Here’s a little exercise in numbers that explains why.

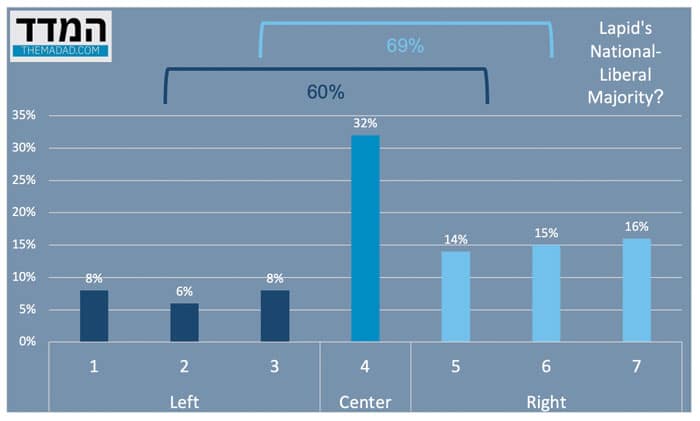

Israel’s Democracy Institute asks Israelis to rate their political positions on a scale of 1-to-7. Those who place themselves at 1 are at the far left of the political map. Those who place themselves at 7 are on the far right. We examined what Lapid’s alliance might look like by looking at this scale. Remember: the magic number is 63%.

In the graph on the right you can see there are two main options: The first, to drop the rightmost group (who answered 7) and the two leftmost groups (who answered 1 or 2). The second, to drop one on the left, and two on the right. In the first case, a larger group is obtained (almost 70%), in the second case, something a little smaller than Lapid’s prediction is obtained (a little over 60%).

Now let’s take one question and examine it on this scale. Should the state fund schools of ultra-Orthodox education that do not teach the core curriculum, such as mathematics and English? This is a convenient question, because it is completely clear how Lapid himself would answer the question. He would reply “do not need to fund.” So, we must assume that the national-liberal alliance he expects consists of those Israelis who would answer this question similarly to him. What happens when we look at this question on the 1-to-7 scale? Lapid’s options shrink to just one option. He must omit two groups on the right, and can omit just one on the left to keep a 60% group.

Of course, the real math that’s needed to identify Lapid’s realignment is much more complex. It must involve a platform that consists of many significant questions and examines whether it is possible to identify a sufficiently significant proportion of Israelis who give similar answers to all of them. This is a test that we cannot do in this limited space. What we can do is to express a hope that Lapid has done his homework, that he knows what he is talking about — that there is, indeed, such a group.

If there is, this could be interesting and encouraging. It has a potential to reshuffle the political map and get Israel out of a long jam. But if it’s not there, we better not to be distracted by illusions that the chances of realizing them are low. Lapid came to convince us that what we see — an Israel that is polarized — is not real. It is natural to hope that he is right. It is essential to remember that the burden of proof is on him.

Something I wrote in Hebrew

On Israel’s “book week” I wrote about a relatively new and quite visible trend: religious women reading romantic-erotic literature:

How do such books impact religious girls and women? … The peace-disturbing possibility is based on the assumption that religious women who are exposed to manifest eroticism may seek out manifest eroticism; it is based on the assumption that religious women who are exposed to sexually charged texts may be tempted into a life that does not resemble the religious ideal. But there is also another possibility. That this is not a subversive literature but rather liberating literature. For religious women who live in a tight, binding, social framework, erotic-romantic literature can be a pressure valve. Reading about one kind of life can balance the need to live another kind of life.

A week’s numbers

A new majority of national-liberal Israelis? Lapid has a fine theory, but whether it’s valid is still an open question.

A reader’s response:

Yael Azulai asks: “Are you not concerned about the coming deal with Iran?” Answer: I am. Both about having an agreement and about not having an agreement. Iran keeps moving forward while the rest of the world seems to get used to the idea of it becoming a nuclear state.

Shmuel Rosner is senior political editor. For more analysis of Israeli and international politics, visit Rosner’s Domain at jewishjournal.com/rosnersdomain.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.