Rabbi Gershon Edelstein

חיים לוי Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license

Rabbi Gershon Edelstein

חיים לוי Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license “At 100, as good as Dead and gone completely out of the world”. This is a Mishna, from Pirkei Avot. Rabbi Gershon Edelstein, the leader of the Litvak ultra-Orthodox community who died May 30th, was little more than a hundred, and must have known the commentary of the Gaon on this Mishnah — a commentary indicating its source: Isaiah 35. In future days, says the prophet, “Someone who dies at 100 years Shall be reckoned a youth”. So, that’s the vision for the days of Messiah. Which may be interpreted as contradiction to the popular belief that the expected age is 120, as was the age of Moses when he died.

Be that as it may, Rabbi Edelstein passed. His funeral attracted hundreds of thousands. What is it that they mourn? Good question. If a 100-year-old person is already considered “dead and gone”, there is nothing to mourn. Still, there is grief. A great sage had died. A community leader had died. Only a year has passed since he became the prominent leader of the Lithuanian ultra-Orthodox, with the death of Rabbi Chaim Kanievsky. The Haredi community tend to enthrone elderly leaders, which ensures frequent turnover.

Length of tenure is important. Pope Benedict served for seven years, Pope Francis is completing a decade. Not by chance, their influence is not comparable to that of their predecessor, John Paul II. There are of course many differences of style and character and circumstances that made the Pope of the late 20th century so influential. But the duration of his term was also of consequence. Pope John Paul II served for more than a quarter of a century. The duration of a leader’s tenure allows him to set a long-term agenda and implement it. Rabbi Edelstein did not have time to lead beyond routine decisions. Neither did Kanievsky before him. Who was the last great rabbi with the ability to make a difference? Some will go back to the days of Rabbi Elazar Menachem Shach back in the ’80s. His influence was evident for about 30 years. Whether this was a positive or a negative influence is beside the point, and a question of ideological position. But there is no doubt that he set a path and made sure that the public progressed on it.

It is often said that Haredi society has been in a leadership crisis for quite a few years now. Rabbi Edelstein had many admirers, but he never had the authority of Rabbi Shalom Elyashiv, or Rav Shach. You can call it, as the Taslmud does, “yeridat hadorot,” the decline of greatness with the passing generations. Or maybe it is the time in which we live — a tough time for leadership, even among Haredim. Or maybe it’s a matter of luck — maybe the next leader will have better health, a longer life, and will serve the time required to anchor his leadership. Either way, leadership upheavals have consequences. What will we see in the Haredi community?

Two possibilities can be offered, one contradicting the other. In the absence of dominant leadership, a group may go through a process of erosion and disintegration. People or subgroups feel freer to follow their own advice. If such thing happens, the common claim about undercurrents that are gradually changing ultra-Orthodox society, bringing it closer to Israeliness, to modernity, could become reality. The argument is often made that these processes are already underway, and ought to be supported and encouraged with patience rather than urgency. Simply put: Maybe the shaky rabbinical leadership of the Haredi public serves the long-term social goals of the rest of the Israeli public.

Of course, there is also a second possibility. Maybe the lack of leadership actually hinders a possible process of integration and slows progress. Why? Because in the absence of a dominant leadership, everyone must take the most extreme positions, so as not to be suspected of striving against the sacred principles. If there’s not a dominant leader, there is no one who has enough authority, enough power, to decide that it is time to make a change.

We’ve seen such case in the past when Sephardic Rabbi Ovadia Yosef was dominant enough to make important, even revolutionary (in ultra-Orthodox terms) halachic decisions, and to implement them. When Rabbi Yosef said something was kosher, his community followed.

Leadership is hard. It is hard at age 50 or 60 or 70, it is close to being impossible for those who are named as leaders close to the age of 100, when they are almost “gone.”

The Lithuanian Haredim do not currently have a leader who has such authority. There is no Mikhail Gorbachev, who rose to power from within the party establishment and then became a reformer. There is no Menachem Begin, who led a political party for a generation, and could convince it to accept a peace agreement that included the evacuation of territories. The Litvak will name a new leader, but leadership is not just something one gets, it is also something one must take, activate, deepen. Leadership is hard. It is hard at age 50 or 60 or 70, it is close to being impossible for those who are named as leaders close to the age of 100, when they are almost “gone.”

Something I wrote in Hebrew

Here’s what I wrote concerning the growing feeling of Israelis that what we need is autonomy for subgroups that would save us the constant bickering over ideological differences:

The idea of “live and let live” is a tempting one. The idea of living together when all that connects us are the “rules of the game” is a tempting idea. But these are ideas that leave a big void in the heart of the Zionist-Israeli project. These are ideas that leave Israel poor and lacking when it comes to cohesion and a shared vision. And this should also be taken into account: A society like ours will have difficulty coming up with an effective response to common challenges and common enemies if it breaks up into groups and tribes, whose partnership loses a dimension of content and becomes a partnership that is mainly technical.

A week’s numbers

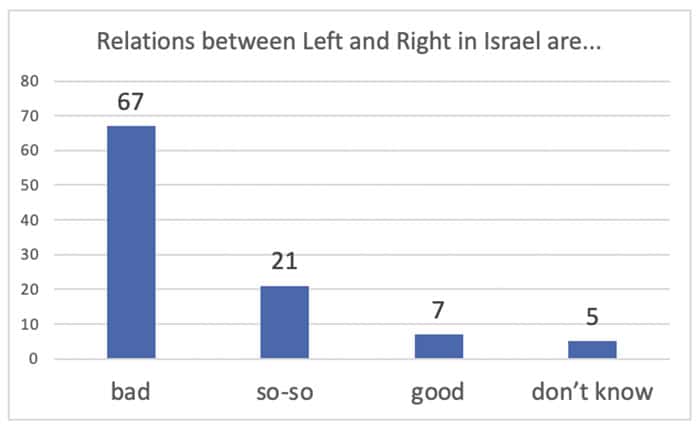

A new IDI survey asked Israelis about the main tensions in Israel and the way they’d characterize the relations between groups. Here’s one finding:

A reader’s response:

Bruno Bergman asks: “why is the crime rate among Arabs in Israel so high?” Answer: that’s complicated. A combination of neglect by the state and the police, and deficiency in political and social leadership in the community.

Shmuel Rosner is senior political editor. For more analysis of Israeli and international politics, visit Rosner’s Domain at jewishjournal.com/rosnersdomain.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.