Keith Lance/Getty Images

Keith Lance/Getty Images On the street where I live in Tel Aviv there is a yeshiva. Young guys in black hats walk around, visit the playground, drag suitcases on wheels, delight us with great singing on holidays. As far as I can see, there is no tension between the neighbors, yeshiva youngsters and mostly secular residents. And yet, whenever I pass by it in the last few months, I look to the sides to see if protesters have already come, if the yeshiva has already been targeted.

There is no reason to protest against the yeshiva, or to harass its students — except one: The growing desire of many Israelis for separation. This is evident in a battle that is taking place against another yeshiva in Tel Aviv, Ma’ale Eliyahu. City Hall decided to reexamine the approval given to the yeshiva to erect a larger building. Protesters against the yeshiva makes themselves visible. There is a campaign for and against, in which the main arguments can be summarized as follows:

On the one hand, Tel Aviv is open to everyone, and it’s a pluralistic city, so why not let a yeshiva operate and flourish without interruption?

On the other hand, Tel Aviv is mostly secular and liberal, and religious-Orthodox leaders, who would not accept secular/liberal institutions in their own residential areas, should not expect too much hospitality in Tel Aviv.

This is a debate similar in nature to another, very familiar debate: Whether and to what extent democracy should allow the expression of extreme ideas that undermine democracy itself. In the US, where unrestricted freedom of speech is the norm, racists or anarchists are tolerated. In Israel, as in many other democracies, the norm is different. Israel is a democracy that has chosen to prevent, at least in theory, the flourishing of ideas that undermine democracy. It follows the concept of defensive democracy. True — a defensive democracy limits the freedom of expression, which is the lifeblood of democracy. But sometimes (proponents of defensive democracy say) one has to balance different values to reach a stable equilibrium. Freedom of expression can be prevented if or when it threatens democracy itself (and hence, in the long run, threatens free expression itself).

Back to Tel Aviv: supporters of the yeshiva make the argument of freedom; opponents of the yeshiva make the argument of defensiveness. Both claims are colored by the politics of the last few months, the politics of separation. The yeshiva was established decades ago, and no one seemed to care, but now its presence is becoming an issue. The yeshiva is a victim of a tense situation.

Who’s right and who’s wrong? This is not an easy question. On the one hand, it is easy to sympathize with yeshiva students who did not sin. On the other hand, it is impossible to expect that Tel Aviv will happily host an institution whose founders’ intention is to alter the city’s character and spirit. Then again, how can we call the city pluralistic if it does not allow a peaceful Torah study? Then again, why can’t seculars behave like the Orthodox and strive to have a cohesive public sphere?

The argument made by yeshiva proponents is problematic: They want Tel Aviv to be open to everyone, while their neighborhoods, and even their cities, will not be open to everyone.

In the Orthodox community, influencers and leaders rose up to defend the Yeshiva. But ask yourself: Would they accept a pride parade in Haredi El’ad? Would they allow the establishment of a school for atheism in Beitar Elit? Would they allow anti-religious activists establish a community in Ofra? The answers are no, no and no. They would not agree. Thus, the argument made by yeshiva proponents is problematic: They want Tel Aviv to be open to everyone, while their neighborhoods, and even their cities, will not be open to everyone.

And in Tel Aviv, which was indeed always open to everyone, new winds are blowing. To sum them up: there is a growing feeling that perhaps it is time for the liberal sector to become, well, a true well-defined and well-defended sector. Maybe Tel Aviv should also be ultra-Orthodox in its own way. To be a city that is a little less ideologically diverse, a little more oriented to the needs of those who identify with the basic values of the majority of its residents. And of course, it is complex when it comes to a large, central city, which is not homogenous at the moment. But the strategic goal is important.

Consciously or unconsciously, this is what is reflected in the battle over the yeshiva in Tel Aviv. The aspiration for a trend of fences and separation. In recent polls, a large majority of Israeli seculars say they do not want to live with ultra-Orthodox groups in the same neighborhood. In all, about 60% of Israeli Jews believe that separate neighborhoods for secular, religious and ultra-orthodox are preferable to mixed neighborhoods.

There’s a short distance from neighborhoods to cities. And if the space is separated, maybe there’s no reason for a conservative yeshiva, whose stated goal is “strengthening spirituality and values in the city”, to have a place in the heart of Tel Aviv.

Something I wrote in Hebrew

Here’s what I wrote as I criticized and also tried to explain why an Israeli TV anchor didn’t said that Haredim are “blood suckers” (because of their budgetary demands):

Israeli Jews have lost their sensitivity to antisemitism. They shout “antisemitism” when it suits them, when someone criticizes them or Israel, rightly or wrongly, but they no longer have a real sensitivity to this phenomenon. Life in a majority Jewish state has worn out their senses. The Zionist rhetoric has worn out their senses. This should also be said: At the heart of the Zionist idea nestles a rejection of the old Jew, and there is also the internalization of negative feelings and negative stereotypes concerning him … almost naturally, it is attached to the Jews whose appearance is the most diasporic — that is, the ultra-Orthodox.

A week’s numbers

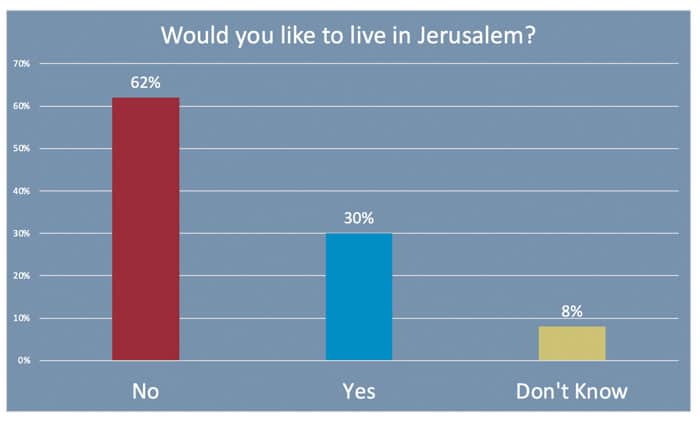

Jerusalem is important, it is also poor, conservative, and complicated. Not all Israelis see these features as a plus.

A reader’s response:

Deborah Levy asks: I just heard that Israel has a two-year budget rather than annual budget, is that normal?

Answer: Normal for Israel. It is a trick aimed at stabilizing the political system (passing a budget is a political obstacle for all governments).

Shmuel Rosner is senior political editor. For more analysis of Israeli and international politics, visit Rosner’s Domain at jewishjournal.com/rosnersdomain.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.