Amir Levy/Getty Images; Bill Pugliano/Getty Images

Amir Levy/Getty Images; Bill Pugliano/Getty Images 4,682 years after the creation of the world, in the year 922 C.E., Jews assembled to celebrate the Seder night on two different days. Thus begins chapter six of a book I wrote a few years ago. With a story that symbolizes our ability to divide. That year – 922 – Jews who lived in Land of Israel started Passover on a Sunday, whereas in Babylonia the Jews gathered to mark the exodus from on Tuesday. When the Jews in Israel had already asked the four questions, the Jews in Babylonia were still burning the leavened foods they had found. When the Jews in Babylonia were still drinking the four glasses of wine, the Jews in Israel were in the middle of Chol Hamoed – the intermediate festival days. Two major Jewish communities – two different calendars.

This is an example of an acute crisis in Jewish relations because of legal interpretation. In the period during which the Land of Israel was under Muslim rule, from 638 C.E. to the end of the 11th century, Jews were allowed to return to their homeland. This is when the great drama of schism over the Jewish calendar occurred, a drama in which two eminent Jews played the leading roles. One was Saadia Gaon, who lived in Sura, Babylonia. The other was the less known Aharon Ben Meir, who lived in Tiberias in the Land of Israel. The sensational discovery of the Cairo Genizah in the 19th century revealed previously unknown details about the huge controversy between these two men, which divided Jew from Jew, date from date, and holiday from holiday.

I was reminded of this story as I prepared myself for celebrating Pesach of this year, with echoes of last week’s events still ringing in my ears. Not many people realize this, but we were very close to having another Pesach for the ages. Last Sunday night, when hundreds of thousands of Israelis took to the streets determined to send a message to the government that it must halt its legislative horses, a conversation about Seder night had already begun. Many protesters, dead serious, were planning to pass the first night of Passover having a Seder of disorder. In Hebrew – Seder means “order”. So – translated properly – they were planning something that sounds like “an order of disorder”, a “Seder shel E-Seder”.

Imagine that: Israelis on the road, to have their Seders with family, meeting other Israelis blocking the roads, preparing to have their one-in-a-lifetime Seder of protest and discontent.

Imagine that: Millions of Israelis on the road, to have their celebration with families all around the countries, meeting hundreds of thousands of other Israelis blocking the roads, preparing to have their one-in-a-lifetime Seder of protest and discontent. It could have been a night to remember. It could have been a nightmare. It would have been both.

The exact reason underlying the year 922 dispute is complicated, and somewhat esoteric. It concerns the procedure by which Jews calculate the lunar conjunction, which is the moment that determines the start of a new month, and the consequent fixing of the Jewish calendar and its festivals. But like many other differences of opinion between Jews, the critical question that Saadia Gaon and Ben Meir bickered about was not how to calculate the calendar, but rather who was authorized to decide which method would be employed to do so. It was a debate over authority. How strangely remote from our current reality, and yet, how relevant. Jews having a fight about the nuanced reading of legal proceedings. Jews have a fight about who has the authority to determine the proper reading of the law. It is the courts? Or maybe the politicians? Sometimes, an obscure debate becomes a matter of great strife. Sometimes, what seems like a crucial argument ends up being almost bizarre. Truly – you celebrated in two different dates because of this? Seriously – you considered celebrating on the main road because of that?

In many Diaspora Jewish communities, as I wrote in another book – #IsraeliJudaism – it is conventional to add politically charged texts and rituals to the Haggadah. For Seder night in 1969, which coincided with the one-year anniversary of the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. in the United States, American civil rights activists composed the “Freedom Haggadah.” But in Israel, as I reported when the book was written, a few years ago, the inclination to politicize the Haggadah is not as strong. Israeli families are fulfilling the vision of Theodor Herzl, whose novel Altneuland includes a fairly traditional Seder night in Tiberias at its core.

Is this changing? It’s too early to say. An attempt to convince Israelis to use an Israeli “Freedom Hagadah”, with texts by authors such as authors David Grossman and Etgar Keret and poet Nurit Zarchi, was made this year. I skimmed through the pages of this document until I got to the last page, where alongside the traditional “Next Year in Jerusalem” appears a modern text by novelist Haim Be’er. “Next year in our Jerusalem that will once again be… a city of justice, freedom and peace, a city of courts… strong fortresses for public integrity”.

Jerusalem?

Be’er is writing about the eternal Jerusalem, but I can still hear the echoes of contemporary protesters that were planning a Seder on the main road crossing Tel Aviv.

Something I wrote in Hebrew

This is one of the mistakes made by the government, when its members attacked the “anarchists” or “evaders”. They thought they were speaking to Old Israel, the one in which evading a summon for military reserve duty was considered a red line. But they were wrong: in today’s Israel, an Israel that has already crossed many red lines, the call to evade such summon was not controversial. This was not a fringe call by fringe people. For a large, powerful camp, it was the obvious policy. You want to know what else most of the protesters supported? Delay in paying taxes, alternative Independence Day ceremonies, disruption of Memorial Day ceremonies, transferring money abroad, blocking roads for long hours. In short, they supported the crossing of many red lines.

A week’s numbers

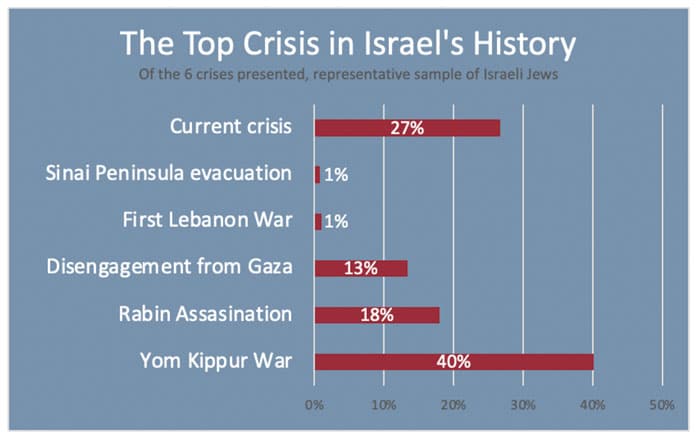

Is the crisis in Israel serious? Here’s what people feel:

A reader’s response:

Alvin Nassau asks: “Were Israelis outraged by Biden’s interference in Israel’s internal affairs?”

Answer: Yes – but some blamed Biden while others blamed Netanyahu.

Shmuel Rosner is senior political editor. For more analysis of Israeli and international politics, visit Rosner’s Domain at jewishjournal.com/rosnersdomain.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.