Photo by Eryn Brydon

Photo by Eryn Brydon Eliad Moreh-Rosenberg clicked to the first photograph of her presentation, and on a large screen at the Skirball Cultural Center displayed a picture of her nondescript workplace at Yad Vashem’s art museum.

“In general, when I say that I work in the art museum at Yad Vashem, people reply, ‘Is there an art museum? I didn’t know,’” Moreh-Rosenberg said.

Murmurs of agreement quietly rippled through the audience of nearly 100 people who had braved a rainstorm to hear Moreh-Rosenberg speak at the Skirball on Jan 31. Since 2014, she has been curator and director of the Holocaust remembrance center’s art division, which houses the world’s largest collection of Holocaust-related art, with more than 12,000 items.

“I think most people don’t know about this — that during this time of complete horror there were sparks of light,” she said. “These Jewish artists fought and struggled in order to create art. Thanks to these artworks, we’re able to learn about life during the time of the Holocaust.”

Moreh-Rosenberg’s presentation at the Skirball, titled, “Art From the Holocaust: Faith and Defiance,” was sponsored by the American Society for Yad Vashem. Founded in 1981 by a small group of Holocaust survivors, ASYV is the American arm of Yad Vashem, Israel’s official Holocaust remembrance site in Jerusalem that draws about one million visitors a year. Moreh-Rosenberg’s talk was part of a weeklong trip to Los Angeles. She also delivered presentations at the Los Angeles Museum of the Holocaust and at several local synagogues and schools.

During her presentation, Moreh-Rosenberg explained that many European Jewish artists risked their lives to scrounge for materials, such as burnt branches to produce charcoal pieces. Many artworks that depicted the reality of life inside the ghettos and labor camps were antithetical to the messaging of the Nazi propaganda machine. Without them, she said, the world would only have had one side of the story.

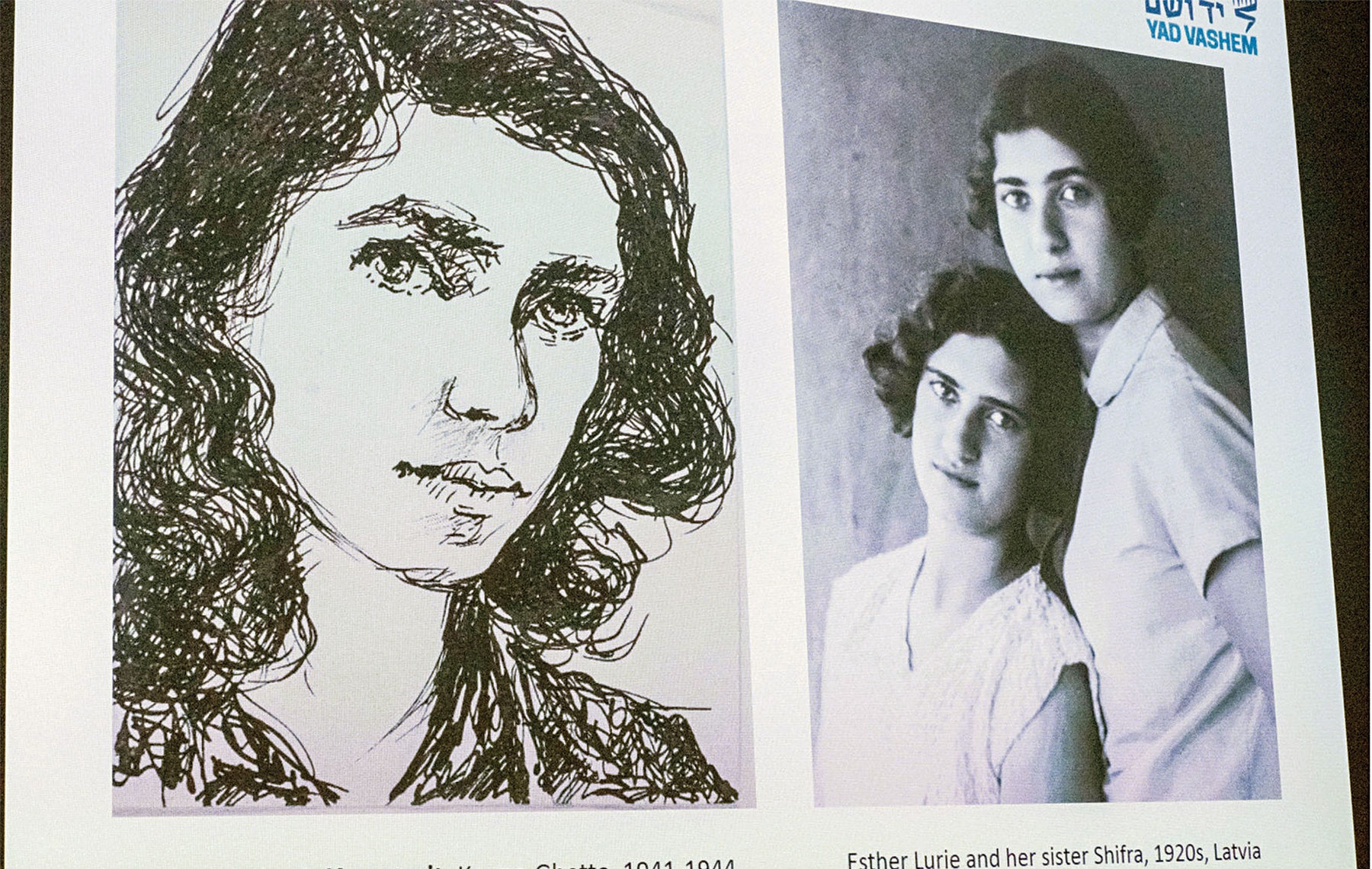

Nearly a quarter of the items in the museum’s collection are portraits.

“And that’s no coincidence,” she said. “Today, we’re able to look at faces. We’re able to, in a way, restore identities. The artist looked at these people who were treated as animals, reduced to numbers by the Nazis. Then, all of a sudden, when the artists looked at them as human beings, and restored them their individual features, they, the subjects, felt like human beings. In this way, the artists were fighting against the dehumanization and were also fighting against the process of annihilation. Because they left these traces, they showed the power of spiritual resistance through art.”

Moreh-Rosenberg highlighted a collection of Holocaust-era artists — some who survived and some who didn’t. Some were trained artists, while others used art simply as a means of personal expression. Among the works she highlighted were those of Petr Ginz, a Czechoslovakian boy who was gassed in Auschwitz in 1944 at the age of 16.

“By bringing the messages of Yad Vashem to the American community, we can help to reinforce the notion that we must stay extraordinarily vigilant in monitoring acts of anti-Semitism.

— Bill Bernstein

A great admirer of the French novelist Jules Verne, Ginz wrote short stories, published a newspaper with other young boys and drew incessantly. “He used his imagination to think about another reality,” Moreh-Rosenberg said. “He loved science fiction. He was a very gifted child.”

Ginz’s drawing, “Moon Landscape,” which depicts a view of the Earth from a jagged lunar surface, garnered acclaim after the war. Ilan Ramon, the first and only Israeli astronaut deployed by NASA, carried a copy of Ginz’s drawing — the original is housed at Yad Vashem — on the fatal mission of the Space Shuttle Columbia in 2003.

At the end of her presentation, Moreh-Rosenberg showed a YouTube video shot by U.S. Astronaut Andrew Feustel, who commemorated Israel’s Holocaust Martyrs’ and Heroes’ Remembrance Day in April 2018 with a video message sent from the International Space Station. Feustel flew to space last March with another copy of Ginz’s “Moon Landscape.”

“May the memories of Petr Ginz, Ilan Ramon and the 6 million lost in the Holocaust always remain in our thoughts,” Feustel said.

“That was particularly moving,” audience member Susan Shapiro, 77, said afterwards. “I didn’t realize that [Ramon] had that picture with him when he went on that Columbia mission.”

Julia Coburn, 17, a high school senior and burgeoning photographer, came to the event with her mother and grandmother. Coburn has taken photo portraits of more than 30 Holocaust survivors for projects at the Los Angeles Museum of the Holocaust. She marveled at the talent of the teenage Ginz.

“I was thinking about how much promise he showed,” Julie said. “And all his work was done at such a young age, at my age.” She paused. “We don’t know how talented he really could’ve been.”

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.