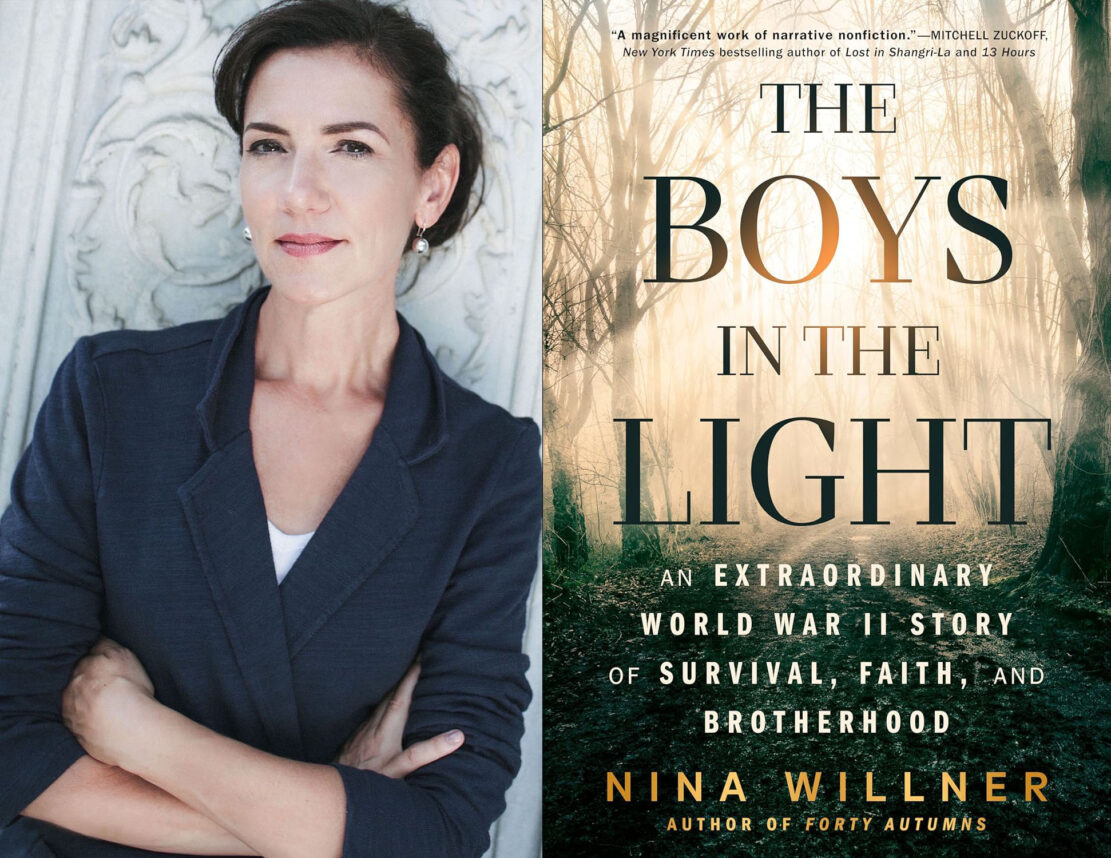

Weekly Parsha: One Verse, Five Voices

Edited by Salvador Litvak, Accidental Talmudist

The Lord further said to me, “I see that this is a stiff-necked people.” – Deuteronomy 9:13

David Sacks

Television writer and podcaster at torahonitunes.com

As the saying goes, if you don’t stand for something, you’ll fall for anything.

Are Jewish people stubborn? Yes. Is that a bad thing? Not necessarily.

And so, I present a tiny ode I’d like to call, “In praise of being stiff-necked.”

Being a stiff-necked people allows us to hold fast to HaShem, and to the Torah, and to the Land of Israel, and to our tzaddikim, and to our commitment to be a light unto the nations, and to the visionary belief that the world is evolving toward perfection, and that the heart will once again be united with the mind, and that light will conquer darkness, and that the whole world will recognize the Oneness of HaShem and finally know who the Jewish people really are, and that the Jewish people will finally know who we really are, so that we can rebuild the Holy Temple, and bring heaven down to earth, and bring an end to hatred, and hunger, and jealousy, so that all of us can take joy in one another’s joy, and realize that we are one big family that shares the same soul, and then we’ll see with our own eyes all the blessings that HaShem has stored up for us since the moment the world was created.

So, is it bad to be stubborn?

Not if it allows you to never give up on the goodness of God.

Judy Weintraub

Chaplaincy candidate, Academy for Jewish Religion, California

Our people are referred to as stiffed-necked not once but several times in the Torah. If we harbor any delusions that we are chosen because of certain superior qualities, this verse stands in contradiction. We often get trapped in our own constrictions. We can’t see beyond our preconceived notions that, because ideas are in our heads, they must be right. Defensively, we are unwilling to turn our heads to see with clarity what is around us. Or we can’t because we simply lack the tools. Either way, that type of resistance can be a detriment that prevents us from getting outside of ourselves.

Perhaps we can look to a favorite passage of mine in Psalms for guidance. “From my narrow place I called you; you answered me from your Expansive Place.” (Psalm 118:5). That expansive place is the majesty of HaShem that is there for each of us to access.

We can loosen the stiffness that keeps our focus narrow, in both a concrete and abstract way. It is available and attainable through the beauty of Shabbat and the treasure that is Torah. In this way, we can reach beyond the constraints of our limitations. May our hearts and minds be open to moving beyond those stiff, narrow places.

Rabbi Aryeh Markman

Executive director of Aish LA

When God said the Jews are “a stiff-necked people,” He was referring to the adult male Jews who had just committed the sin of consenting to the golden calf. The medieval commentator Ramban said the calf was not an idol but rather an attempted intermediary between God and Man to replace Moses. Moses had not returned from Mount Sinai at his appointed time. The men panicked, the women held strong. Why?

Throughout Jewish history, women have played a vital role in creating and molding our nation, beginning with the matriarchs. God agreed to Sarah’s advice to send Yishmael away, lest he be a bad influence on Isaac. Haman’s downfall was caused by Esther.

This strength is a direct result of a woman’s emotional nature. God created women with a higher degree of feeling, thus enabling them to achieve greater spirituality than men. Indeed, scientific studies have proven that the emotional part of a woman’s brain is more highly developed than a man’s.

One of the manifestations of this womanly trait is that an emotional feeling will not concede to false logic. In the case of the golden calf, the men reasoned that where an entire nation of people was left alone in the desert, it was permissible to make an idol to serve as their leader. The women, on the other hand, steadfastly remained loyal to God’s and Moses’ teaching and refused to consent to any logical argument leading to anything that even resembled an idol. They were right.

Rabbanit Alissa Thomas-Newborn

B’nai David-Judea Congregation

When we built the golden calf, God gave us the epithet “a stiff-necked people.” But what exactly does this mean? Rashi explains: “They turned the hardness of the backs of their necks to those who rebuked them, and they would not listen” (comment on Exodus 32:9). A terrible side of us came out — our willingness to tune out God’s advice, rebuke and criticize rather than be vulnerable and have faith. We literally turned our backs to God.

Rather than patiently and faithfully waiting to receive His Torah — which instructs us about how to live, including an obligation to rebuke — we preferred an inanimate idol that would be morally silent. Most of us can relate to this desire to close our ears to feedback and rebuke, whether from family members, colleagues or God. It’s certainly in our spiritual Jewish DNA. But our epithet as a “stiff-necked people” needs not to be descriptive as much as it can be cautionary.

With the golden calf, God was heartbroken that we weren’t willing to listen to Him and be vulnerable and humble. But we can do better today. We will soon begin the month of Elul, the time of year when we accept rebuke — from God and each other — with open ears and hearts. And so, as we face our sins, mistakes and what we need to work on, may what is “stiff-necked” within each of us become humble and malleable. For this is how we grow.

Ilana Wilner

Shalhevet High School

“A stiff-necked people” is commonly translated to mean a stubborn nation. This phrase appears in our Torah portion twice in Chapter 9. The first when Moshe recounts the story of the Sin of the Spies, and the other after Moshe retells the story of the golden calf. The phrase connotes more than stubbornness, but also inability to repent.

Of all the sins throughout Scripture, why in these specific stories does God refer to us as “stiff-necked” and a stubborn nation? In both accounts, God had decided to destroy the Jewish people and start anew, but Moshe convinced Him to forgive the Jewish people. By choosing to forgive and save the Jewish people, God showed the attribute of kindness through flexibility. God is calling us “stiff-necked” to criticize us for not emulating those traits, for not being amenable and doing teshuvah.

So much of Judaism is routine and exact: the height of a sukkah, the amount of matzo one has to eat and at what time Shabbat ends. Yet, here God is teaching us not to focus on the “exact” but to find kindness in being flexible, just as God has shown when He forgave the Jewish people for their terrible sins. We live in a world of eilu v’eilu — these and these are the words God — and it is possible for more than one person to be right. God is reminding us here to make room for others even if we disagree or are different, just as he made room to forgive.