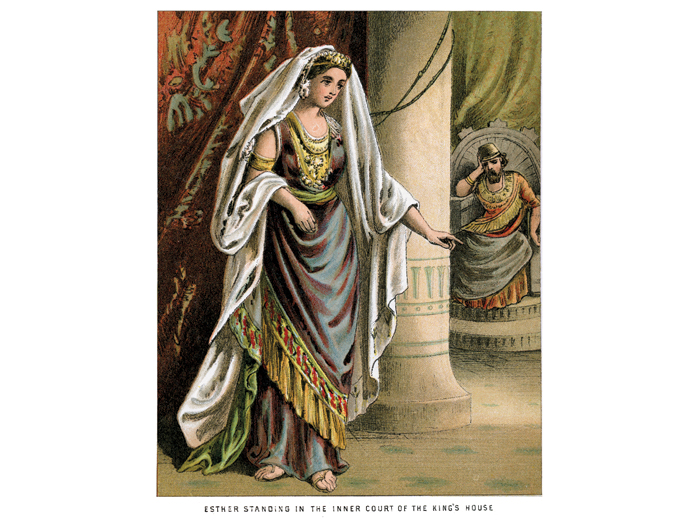

Vintage colour lithograph from 1882 of Esther standing in the Inner Court of the King’s House

duncan1890/Getty Images

Vintage colour lithograph from 1882 of Esther standing in the Inner Court of the King’s House

duncan1890/Getty Images It didn’t happen all at once. It took work to shed the names, accents and customs of our immigrant forebearers, but eventually, we did it. An unspoken bargain was struck: What we would lose in distinctiveness, we would gain in societal acceptance. In the abstract, we longed for a return to the land. “Next Year in Jerusalem,” we said at our seder tables. In practice, we were no longer homeless; the diaspora was our home now. We had made it.

The blessings were real. So, who could blame us for being shocked when the rug was pulled from beneath our feet? People were saying that we were different, that because of our fealty to our people and faith, we had become a threat to the social order. A sharp uptick in antisemitism. Our golden age was over, or maybe, some opined — it was never so golden after all.

Where do we turn for guidance for such a time as this?

Megillat Esther is a remarkably relevant guide as to what it means to be a Jew today. One of the most beautifully crafted of all biblical literary creations, Esther tells the tale of how a diaspora Jewish community navigated its status as a distinct minority in the majority culture of Persia’s capital Shushan.

Having deposed Queen Vashti, King Ahasuerus issues an edict to bring forth every young maiden for consideration to be the new royal consort. While the event is staged the world over as some sort of Miss Persia beauty pageant, it is not clear if this palace proclamation was received as an invitation for social advancement or a fear-inducing edict akin to Pharaoh’s decree against the male children in the book of Exodus. Opportunity and fear: a possibility to move up in which much would be given up.

Esther is introduced. Aside from her physical beauty, we know Esther is a Jew and an orphan, the ward of her foster father Mordechai. Mordechai is actually the first person in the Bible to be called a Jew, Yehudi — referring to one descended from the tribe and land of Yehudah or Judah. Citizens of their host country, but distinct as a people and connected to another land. One senses that Esther’s orphaned status was not just biological. Separated from her family of origin and land, she was Jew-ish, a Judean exile in King Ahasuerus’s court.

When Esther enters the king’s palace, Mordechai advises her to keep her identity secret – the name Esther from the Hebrew astir meaning “I will hide.” Twelve months of oil and myrrh; a makeover process worthy of the best – and worst – of reality TV.

Esther sheds any vestigial traces of her religious identity and assimilates into her non-Jewish environs. She becomes queen by marrying a non-Jewish king – the ultimate act of assimilation. Esther has gained much, but has also left much behind. One wonders how she felt when she looked in the mirror and saw a Persian queen staring back at her.

If the first two chapters of Megillat Esther signal the comforts of Persian Jewish life, it is in the third chapter that the bottom falls out. Haman is promoted in the king’s court and Mordechai refuses to bow down. Haman’s wrath waxes hot. In Haman’s mind, Mordechai’s actions are a reflection on all Jews. Haman brings the matter to the King’s attention:

“There is a certain people, scattered and dispersed among all the other peoples in all the provinces of your realm, whose laws are different from those of any other people and who do not obey the king’s laws … If it please Your Majesty, let an edict be drawn for their destruction.” (Esther 3:8–9)

Ahasuerus, operating either out of willed ignorance or political expediency, gives the green light for them to be destroyed. As news of the edict spreads through the Kingdom, the city of Shushan is “dumbfounded.” They do not seem to bear the same Jew-hatred as Haman, but it would take a rare form of courage to object to him, a fact which Haman was probably counting on. Haman understood that his hatred combined with the king’s enabling and a nation of bystanders was all he needed to carry out his plans.

The decisive turning point arrives in chapter four. Mordechai relays the ominous news of Haman’s edict to Esther, imploring her to appeal to the king and plead on behalf of her people:

“Do not imagine that you, of all Jews, will escape with your life by being in the king’s palace. On the contrary, if you keep silent in this crisis, relief and deliverance will come to the Jews from another quarter, while you and your father’s house will perish. And who knows, perhaps you have attained to a royal position for just such a time as this.” (4:13–14)

Invoking the pull of peoplehood, Mordechai links Esther’s fate both to that of her imperiled contemporaries and ancestral roots. Her true identity will eventually come out, and not even her royal status will offer protection. Both she, and her father’s house, will be wiped out.

Esther knows that Mordechai knows that they both know, that but for the chance events of the prior chapters she would not be sitting on the royal throne. Who knows if it was not “for just such a time as this” that Esther arrived at her position? Now is the time for moral courage.

And for the first time in her life, Esther becomes the protagonist of her eponymous tale. She instructs Mordechai to assemble all the Jews to fast. In breach of protocol, and at great personal risk, she seeks an audience with the king. She may perish, but she will no longer keep her identity nistar, hidden. Esther has come out from the shadows as a Jew, a woman, and a queen, leaning into all three aspects of her being. A heroine for her time, a heroine for our time.

Esther’s persona stands as an enduring parable for Jewish identity. We see our story in the inchoate nature of her early Jewish self and the “bargain” she makes in entering secular society. Post Oct. 7, the scroll’s description of the precarious nature of diaspora existence with its haters, enablers and bystanders hits close to home. We feel for Esther as she squirms in her indecision. “Is this really my fight? I could lose so much – even my life?” Esther’s struggle is very much ours.

Esther risks it all for her people: power, prestige, and social acceptance. Esther didn’t choose her moment, it chose her — but when that moment arrived, she threw her lot in with her people.

And it is Esther to whom we turn for direction on what it means to be a Jew today. Esther risks it all for her people: power, prestige, and social acceptance. Esther didn’t choose her moment, it chose her — but when that moment arrived, she threw her lot in with her people. She leverages her station in life and is unapologetic about her roots and the right of her people to stand tall as citizens and Jews.

Most of all, Esther refuses to let her Judaism be defined by the hatred of others. Kiy’mu v’kiblu ha-yehudim, “the Jews affirmed and accepted,” the text notes in a later chapter (9:27), a verse understood by the rabbis to signal a joyful and volitional acceptance of Jewish identity. Esther the person and Esther the book are important not merely because of what they teach about fighting Jew-hatred. They are important because they teach that Jew-haters do not get to define the Jewishness of Jews – Jews do.

Ours is an Esther moment. We too have made bargains with modernity; we too have assimilated into our host culture only to discover that we are not quite as at home as we thought we were. Who knows if it was not for just such a time as this that we arrived at our station? Some things are better not left to chance. As did Esther, may we stand connected to our people, vigilant on behalf of their well-being and, most of all, living proud, joyful, and honorable Jewish lives.

Elliot Cosgrove is the rabbi of Park Avenue Synagogue, Manhattan.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.