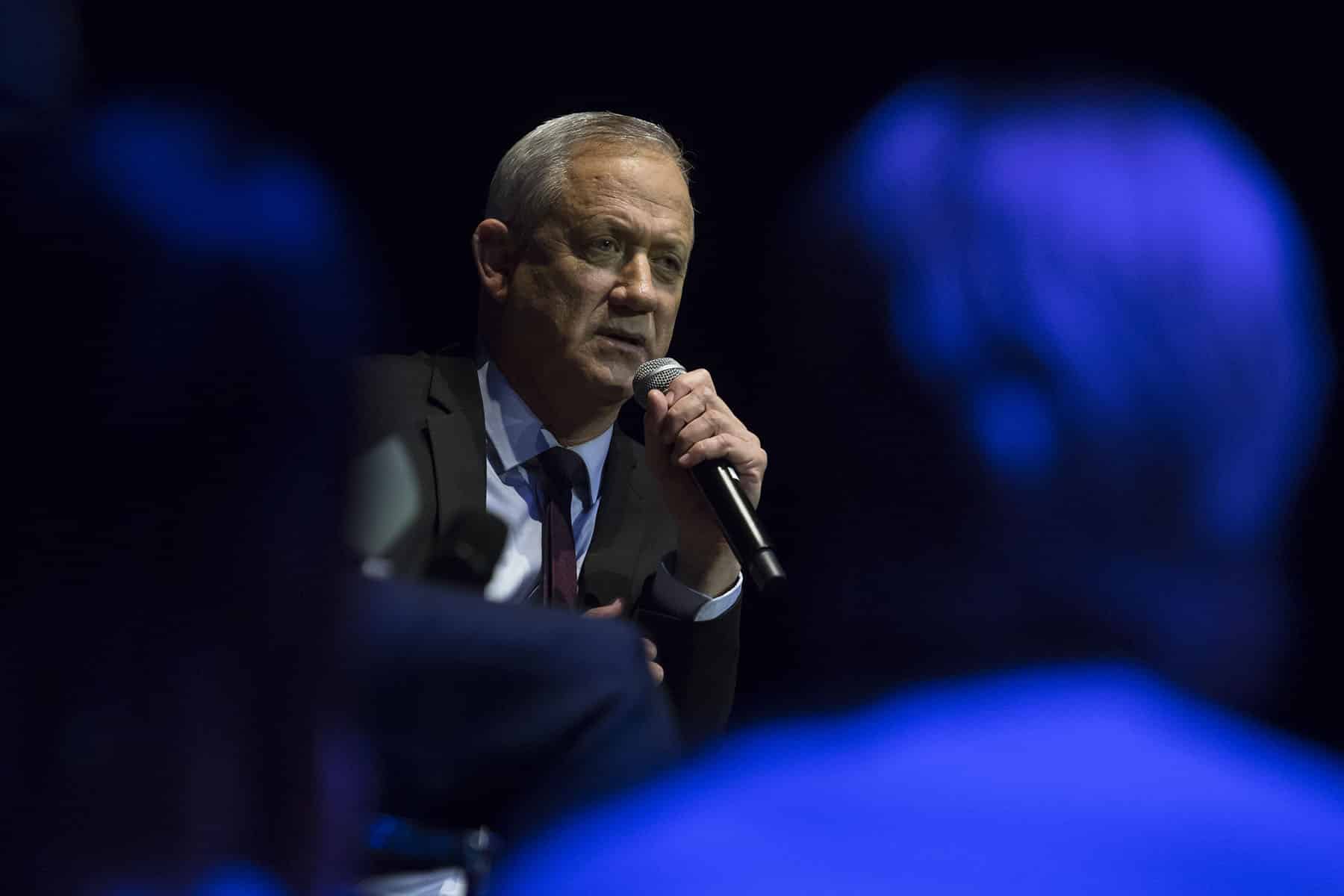

Many of the Israelis who have voted for Blue and White and Labor, are furious at what they perceive as the betrayal and vote-stealing by Benny Ganz and Amir Peretz. However, instead of crying over spilt milk, they should rather take a fresh look at the Israeli society and search for new allies with whom they could secure a better future for Israel.

In his memorable speech at the Herzliya Conference in 2015, President Reuven Rivlin divided the Israeli society into four “tribes”: Seculars, Orthodox, Ultraorthodox and Arabs, calling for the creation of a new “Israelihood” which will be inclusive of all four. IDC Herzliya, the host of the conference, stood up to the occasion, and established “The Center for Shared Israelihood.”

However, a survey held soon after poured cold water on the enthusiastic founders. “The majorities in the four tribes,” lamented the new director of the Center Prof. Alex Mintz, “don’t believe that it is possible to create an Israeli society, Jewish and democratic, which will contain them all.”

Except that David Ben Gurion would have never founded Israel if any time he bumped into harsh reality he would give up. In that spirit, believers in a progressive, Jewish and democratic Israel, should seek potential allies to this vision, and join them through uneasy compromises, without giving up the ultimate goal.

The Orthodox would have been the natural allies, had they not been obsessed half a century ago with settling in Judea and Samaria, which is indeed the cradle of the Jewish People but today is densely populated by Palestinians. More settlements, and now annexation, might doom Israel either to lose its Jewish character or to become an apartheid state. The Ultraorthodox are not partners either, because most of them prefer to remain in their close-knit communities. We are left, then, with the Israeli Arabs.

No doubt that an agreement between secular Israeli Jews and Israeli Arabs about a shared Israelihood is a formidable challenge. In their book Limited Partnership: Jews and Arabs, Prof. Tamar Herman and her colleagues from the Israel Democracy Institute found that the majority of Israeli Jews (68%) believe that one can’t feel part of the Palestinian People and yet be a loyal Israeli citizen. On the other hand, most of the Arab interviewees (67%) said that Israel shouldn’t be defined as the nation-state of the Jewish People.

David Ben Gurion would have never founded Israel if any time he bumped into harsh reality he would give up. In that spirit, believers in a progressive, Jewish and democratic Israel, should seek potential allies to this vision, and join them through uneasy compromises, without giving up the ultimate goal.

A dead-end, you may say, but going back to the survey of the Center for Shared Israelihood, we surprisingly discover the full half of the glass: In stark opposition of what the Orthodox and the Ultraorthodox say, 49% of the Israeli Arabs and 47% of the Israeli seculars believe that living together is possible. Another survey, taken by the Jewish People Policy Institute, showed that this year there was a sharp increase in the number of Arabs who define their main identity as “Israeli”, rather than “Arab” or “Palestinian”. And finally, another look at the data of Limited Partnership reveals that an overwhelming majority (89.5% of the Jews and 95% of Arabs) who have met at work define the relationships as good and very good. Needless to say that the Covid-19 crisis has surely contributed to this trend, with so many Arab doctors and nurses fighting on the frontline of the plague.

From this starting point, we can proceed towards full equality, by amending the recently legislated Nation Law, by introducing an equality article in the spirit of the Declaration of Independence. In the meantime, on the hard, national issues, we will have to agree to disagree.

Embarking on this path, which would augment the prospect of Israel to remain a progressive, Jewish and democratic state, Arabs and secular Jews will have to make painful compromises, change worldviews, get rid of old habits and elect different leaders.

If such a move happens, secular Jews and Israeli Arabs can lean on their next generation. According to the Central Bureau of Statistics, in 2024 the schools in Israel will include 879 thousand secular pupils, 437 thousand Arabs, 279 thousand Orthodox and 384 thousand Ultraorthodox. Seculars and Arabs, then – the two groups more believing in coexistence than others – have impressive human reservoir. Imagine the potential of these numbers when the children get from their parents and teachers messages of mutual respect, equality and democracy.

Embarking on this path, which would augment the prospect of Israel to remain a progressive, Jewish and democratic state, Arabs and secular Jews will have to make painful compromises, change worldviews, get rid of old habits and elect different leaders. In doing so, they should embrace the only aphorism I remember from a course in Arabic I took ages ago: Bidak einab v’la tkatel alnator, you want to eat grapes or fight with the guard?