One of my favorite memories of Shabbat meals at my parents’ home is the lentil soup. Hot, dark-red soup with marrow bones at the bottom of the bowl was a

sumptuous treat on those cold and wintry Friday nights.

Since then, I’ve discovered that lentils are not only delicious, they’re nutritious. Go to any Web site on healthy foods, and you’ll learn:

- Lentils are high in fiber, folate and magnesium, and all three contribute to the prevention of heart disease;

- Lentils help stabilize blood sugar levels, so they’re especially healthy for people who have hypoglycemia or diabetes;

- Finally, lentils can increase your energy by replenishing your iron stores. Lentils’ red color is due to their richness in iron — a vital ingredient for hemoglobin contained in our red blood cells that transports oxygen to all the body’s cells.

Could this be one of the reasons why Jacob fed Esau lentil soup? After all, Esau had just come in from the field, exhausted after a long day of hunting. A hearty bowl of lentil soup would have been just what the doctor ordered to replenish his depleted body.

And yet, the Zohar tells us quite the opposite. The ancient text states that Jacob deliberately prepared lentils to feed his evil brother in order to weaken him, because red foods have a tendency to weaken one’s blood.

Was the Zohar simply spouting bad medicine?

I don’t think so. I believe the Zohar knew that lentils are a food that interacts with the eater’s bloodstream. Jacob knew that on a metaphysical level, by his contributing to Esau’s blood, Esau would not have the same bloodlust against his brother, Jacob. The best way to disarm your enemy is to contribute to his arsenal. The enemy now feels enriched by your gift and is thereby conflicted about using your own weapons against you.

This was Jacob’s strategy: Let me strengthen my brother, especially his blood. This way, part of me will be within him, and his strength will be compromised should he ever attempt to rise up against me.

Our sages offer another reason Jacob was preparing lentils. His grandfather, Abraham, had just passed away, and Jacob was preparing the traditional mourner’s meal. As we know, a mourner is supposed to eat a round food upon returning from the cemetery. In Europe, and later in America, that food has traditionally been round, hard-boiled eggs. But in earlier times, that round food was the lentil.

Why does a mourner eat a round food? The circle represents the circle of life, and it is supposed to remind the mourner that life is cyclical: The tragedy of death that has stricken me today will strike my neighbor tomorrow. Death is the one phenomenon that equalizes us all and spares no one. Such is the way of this world.

Perhaps, this was also Jacob’s subliminal message to Esau in presenting him with those same lentils. Life is cyclical, brother, so that “what goes around, comes around.” Bloodshed begets bloodshed. Be forewarned that should you ever be tempted to rise up against me, your violence will only come back in the future to haunt you.

Especially since the elections, we have seen Jew rise up against Jew with anger, malice and hatred. Yes, the issues are vitally important to both sides, and the passions run extremely deep. Let us remember, however, the lesson of the lentils.

Firstly, the best way to disarm our opponent is to “kill him with kindness,” that is, to offer a gift of ourselves that will be absorbed deeply into the bloodstream. The more we can imbibe of each other’s ideologies, at least to understand the other’s mindset and where they’re coming from, the more we’ll be able to commence dialoguing rationally and civilly.

Finally, remember that bloodshed begets bloodshed. No matter the righteousness of the cause, there is no act of violence or demonization against our brother that can be excused. It will eventually boomerang, and no one will be the richer for it; our people simply cannot afford it.

May we live to see the day when, despite our disagreements, despite the disparity of our views, we can live together in peace and harmony.

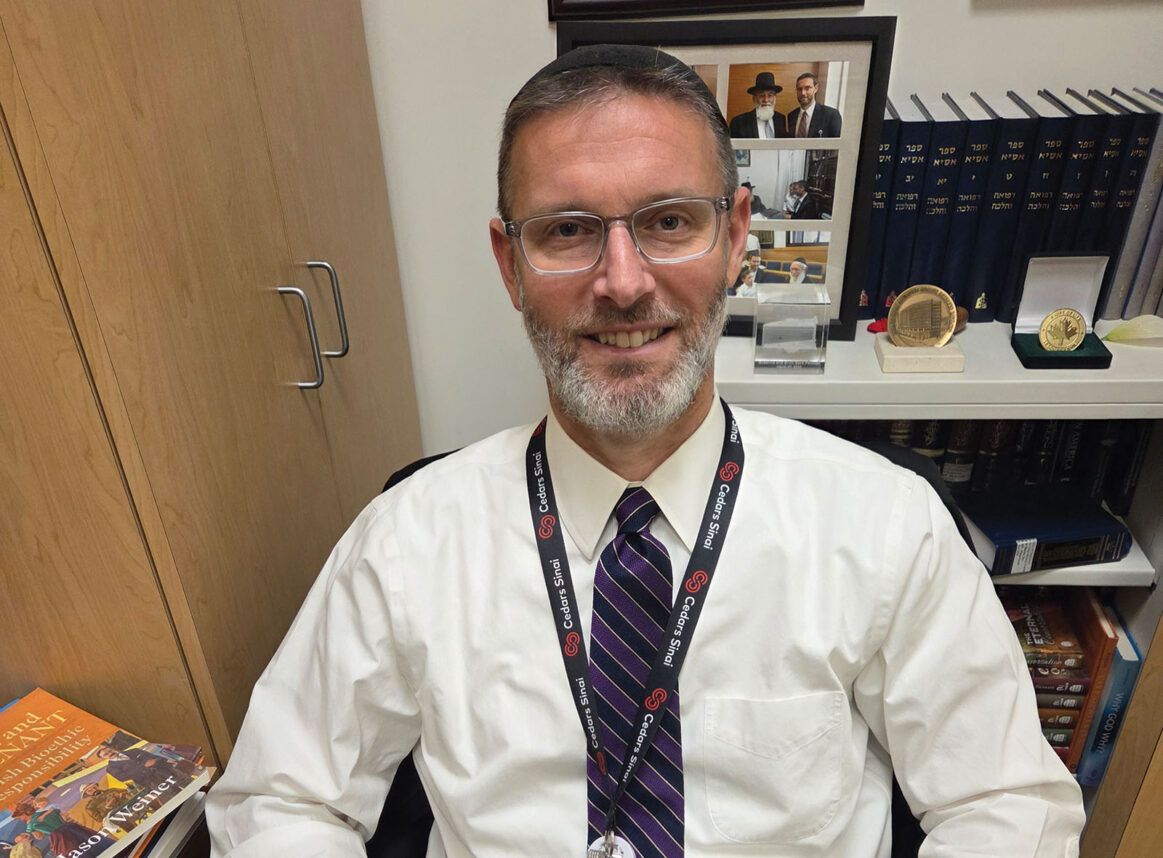

Rabbi N. Daniel Korobkin is rabbi of Kehillat Yavneh in Hancock Park and director of community and synagogue services for the Orthodox Union West Coast Region.