There is nothing quite like walking through a jetway to or from an El Al plane at Ben Gurion International Airport and seeing poster after poster lining the passage touting the work of the International Fellowship of Christians and Jews — nearly every banner featuring larger-than-life photos of Rabbi Yechiel Eckstein.

My daughters and I have joked for years that those posters surprised us during each visit to Israel any of us took. I knew Eckstein for more than 25 years — since the early days of the Fellowship, when he lived in Chicago; we often would meet when he visited New York. Although I shared his critics’ reservations about accepting millions of dollars from evangelical Christians whose motivation was, Eckstein insisted, to follow the passage in Genesis in which God tells Abraham, “I will bless those who bless you,” thinking Christians did so because of their eschatological and geopolitical beliefs, I was very fond of him.

Since he founded the Fellowship in 1983, Eckstein and his organization raised more than $1.6 billion, according to a statement the group issued Feb. 6, after he died of apparent cardiac arrest at age 67 in his home in Jerusalem.

Eckstein was as excited as a schoolboy while he planned to make aliyah, which he did in 1999. I remember meeting with him in the offices of JTA, where I worked then, and being charmed and touched by his heartfelt enthusiasm. For Eckstein, who was an ordained Orthodox rabbi, it was the fulfillment of a lifelong dream.

I watched his organization grow from startup to behemoth, as his (perhaps justified) sense of importance grew proportionately. But somehow, it always seemed to me, his unbridled enthusiasm for his work made him a charming guy with a down-to-earth quality that he

never lost.

His daughter Yael, who is the Fellowship’s global executive vice president, is expected to continue his work.

Eckstein pioneered soliciting donations from Christians for the benefit of Jews by broadcasting late-night television commercials that still seem ubiquitous if you watch TV in the wee hours, and often aired on Christian radio stations. In marketing the Fellowship, Jews are portrayed as poor and needy. Eckstein asked for his Christian viewers’ donations to support Holocaust survivors and those living in the former Soviet Union. The Jews portrayed aren’t brawny sabras, Israel Defense Forces veterans or startup geniuses creating tech to sell to the world’s major app or software companies. Jews in his marketing campaigns are babushka-wrapped, wizened, old people freezing in the former Soviet Union. You can see his TV ad here: ifcj.org/tv.html.

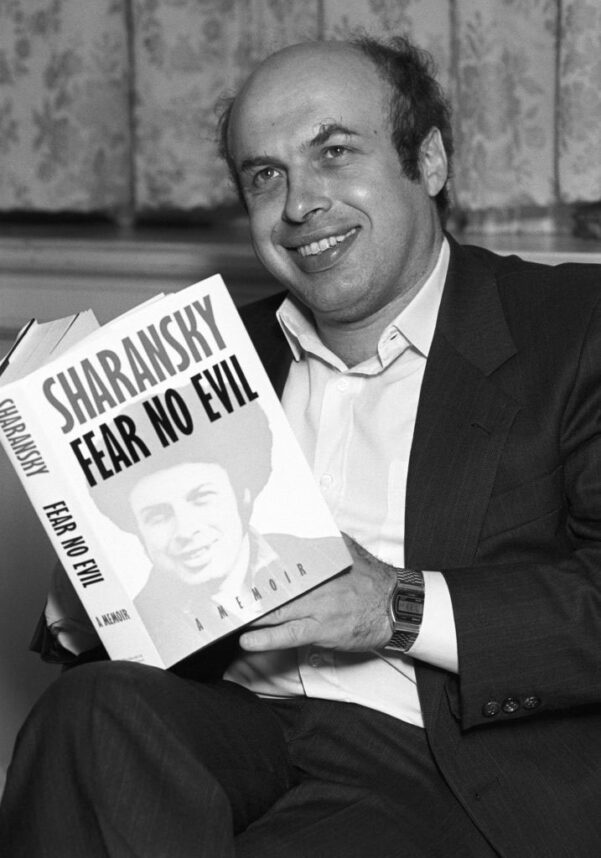

He was the face of Jewry to much of the American evangelical Christian community — the only Jewish figure some would ever “meet,” through his television ads and appearances on the Christian Broadcasting Network. And he cut an appealing figure, with a blend of boyish looks and sincerity. The Fellowship’s website (ifcj.org) includes a variety of educational material geared toward Christians, about Jewish holidays, the Holocaust and angels.

Eckstein had the unique ability to bridge the Jewish and evangelical worlds, because he spoke the language of both. He moved easily from talking about a sense of being called to bless others, to using that combination of Hebrew and English slang specific to Anglo immigrants to Israel while expressing frustration with Jerusalem’s municipality, for instance.

At one point, Eckstein was funding the aliyah of more immigrants than the Jewish Agency was, and he wanted recognition that the Israeli establishment was loath to give. So he broke away and started his own aliyah program, filling planes with new immigrants.

When my daughter Aliza and I visited Eckstein just over a year ago at the Fellowship’s headquarters in Jerusalem, he was eager to tell me about the many programs his work was funding around Israel as well as in the former Soviet Union — ranging from soup kitchens to day activity programs for impoverished senior citizens and the disabled just across the street from his office. He would regularly visit to give hands-on help at that center, he said.

For all my unease with Eckstein’s closeness to people like Rev. Pat Robertson and Rev. John Hagee, whose views on things such as abortion and the civil rights of minority groups, as well as Israel’s hoped-for peace process, are diametrically opposed to mine and those of most American Jews, I couldn’t help but be impressed with the work he was doing, funding programs for the needy that Israel’s government didn’t.

Within minutes of meeting my daughter, Eckstein had given us two autographed copies of his biography and offered Aliza, who was in Jerusalem for a gap year between high school and college, an interesting-sounding internship. That was Eckstein — both his ego and his generosity could be on display in the same moment.

Eckstein was larger than life. He had tremendous and enthusiastic energy for his work and a sincere belief that he was repairing the world. And although I felt uneasy about the motivation and influence of some of the people he considered his closest allies in the work, one thing was clear to me: He was unwavering in his faith.

He will be missed.

Debra Nussbaum Cohen writes from New York for Haaretz and is a contributing editor at The Forward.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.