“Fourth bar mitzvah. This must be easy for you,” my friend Maureen says.

“I’m a loon,” I answer.

“But you’ve already done this three times.”

“Doesn’t matter.”

It doesn’t matter, because I still have to make sure that Danny learns his eight aliyot and his haftarah, writes his d’var Torah, d’var haftarah and personal prayer and fulfills our synagogue’s mitzvah requirements for a Gold Kippah.

It doesn’t matter, because I still have to compile a guest list, pick out invitations, type an address list and deal with delinquent R.S.V.P.s. I still have to find a party venue, decide on decorations, sort through 13 years of photographs for the video montage and order kippot. And I still have to needlepoint a tallit bag and atara (collar) for the tallit.

It doesn’t matter, because each child is different, and each bar mitzvah strikes a different point in our family’s trajectory.

“Every bar mitzvah is the same, and there is none like any other,” Morley Feinstein, our senior rabbi at Los Angeles’ University Synagogue, says.

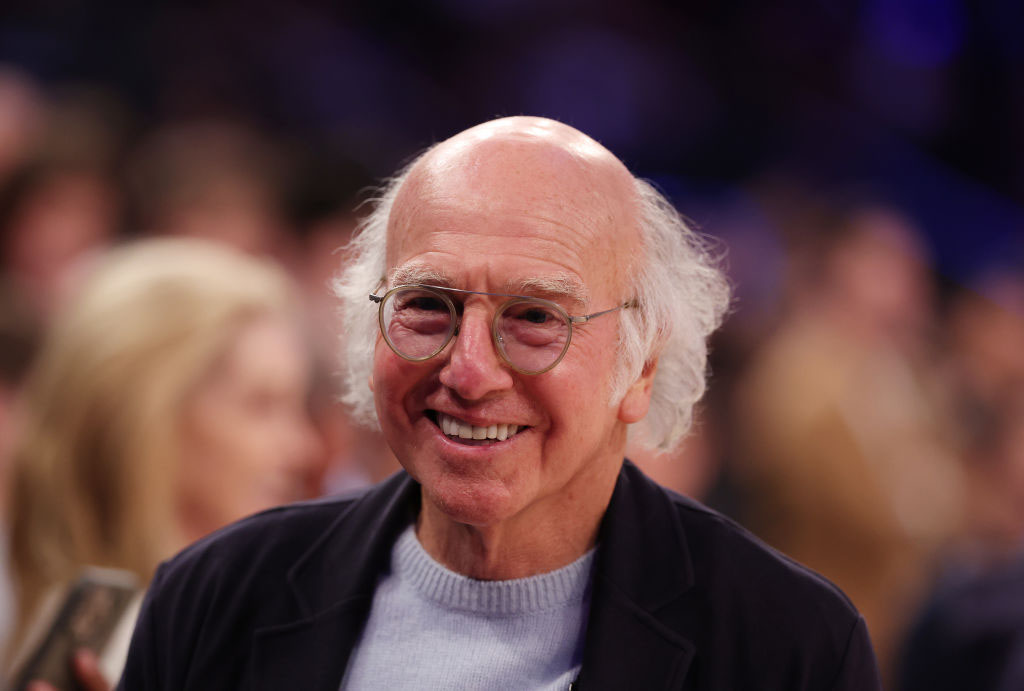

Seven years ago, with our first bar mitzvah, Larry and I were dealing with a 5-, 7-, 9- and 13-year-old. The biggest challenge was getting the four boys in and out of outfits for the Friday night dinner and service, the Saturday morning bar mitzvah and the evening celebration. And keeping track of 12 pairs of black socks in three different sizes.

Seven years ago, with Danny in kindergarten and Zack just 13, we were bemoaning the loss of our last preschooler and apprehensive about entering the turbulent world of teenagers.

Seven years ago, my father was alive.

Now, Danny can legitimately see a PG-13 movie, and Larry and I qualify for AARP membership. There are no more children, only teens and a post-teen.

“It’s bittersweet,” Larry says.

“No, it bites,” I reply.

And so, refusing to acknowledge this familial tectonic shift, I concentrate on how many tricolor light sticks to order and how to create place cards that resemble bookmarks. I concentrate on buying new towels for the bathroom and new plants for the living room. And I concentrate on finishing the atara.

“I don’t want this bar mitzvah to happen,” I tell Rabbi Feinstein, blinking back tears.

But beyond my distractions and denial, I can see that this rite of passage, which was created in the Middle Ages, has a life and insistence of its own. That this is the natural and ineluctable progression from Danny’s bris, where Larry and I promised to bring him up to a life of Torah and good deeds and, eventually, marriage. And a time when Larry and I will hand down the Torah to our grandchildren.

And beyond my distractions and denial, I can sense something transcendent happening as Danny prepares for his bar mitzvah, which, seemingly contradictorily, celebrates both change and continuity, and which connects Danny to both his ancestors and his descendants.

“What is unique about Judaism is that we mark the beginning of adulthood with acts of learning and acts of loving kindness, rather than some physical activity,” our cantor, Jay Frailich, says.

Indeed, rather than banishing our adolescent to some isolated wilderness, tempting as that sounds, we surround him with family and friends to mark this rite of passage publicly. And with months of preparation, with time to contemplate, question and, in my case, complain, we mark this rite of passage consciously. Danny is not slipping unaware into adolescence, nor Larry and I into immutable middle age.

And so, I begin to think about what I want to say to Danny on the bimah. This child who was born with an innate sense of right and wrong; who can hold his own with three older brothers, actually commanding their respect; who sticks up for other people.

This child who reads sections of three newspapers daily; who loves to debate and watch the Dodgers; who hates George Bush.

This child who became an adamant vegetarian at age 8; who wants to be a litigator, economist or therapist; who loves poker and “Uncle John’s Bathroom Reader”; who is a world-class worrier.

This child who constantly says, “If I weren’t here, you and dad would have a hole in your heart, and you wouldn’t know why.”

But he is here. And he is becoming a bar mitzvah.

Beyond my tears, I am grateful that Judaism gives us the ritualistic framework to stop and take stock of life’s significant transitions.

Beyond my tears, I am grateful for this son who has filled an unknown hole in my heart. And for this family that nourishes and sustains me, and that now can keep track of all their own socks.

Jane Ulman is a freelance writer who lives in Encino with her husband. She has four sons.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.