When Anthony Kantor was orphaned on Russia’s streets a century ago, narrowly escaping the pogroms that killed his family, he couldn’t have imagined that he would one day make his living trading diamonds and other precious stones in downtown Los Angeles.

Nor did the late Kantor, a founding member of Hollywood Temple Beth El and an underwriter of Bais Yaakov High School for Girls, dream of the impact his success in the diamond industry would have for Jews in Los Angeles.

Kantor’s daughter, Irene, son-in-law, Conrad Furlong, and grandson, Aaron Henry Furlong, expanded the business begun by the Russian street child, who closed deals with a handshake and a mazel und brucha (luck and blessing), the traditional closing of a deal in the diamond trade. For the past 35 years, the Furlongs have designed and manufactured high-end jewelry in their Hill Street office tower, located in the heart of Los Angeles’ Diamond District. They are one of many third- and fourth-generation Jewish families who have had a profound impact on the enigmatic and tightly knit jewelry industry.

"Back in my grandfather’s time, the diamond business was almost entirely Jewish," Aaron Furlong said, as he graded small stones. "Mazel was your word, and if you went against it, you were ostracized from the business."

Today, estimates put the number of Jews in the diamond trade at roughly 50 percent. Immigrants from countries like Armenia, Lebanon, Turkey and India have poured into Los Angeles’ diamond center, much like the wave of Eastern European Jews did after World War II.

"Despite the changes," Furlong said, "this industry is still mostly family run. There’s a long-standing code of ethics, and reputation is the only thing that separates the different firms."

The mazel code that Furlong cited — mazal u’bracha in Hebrew, mabruk in Arabic — has guided generations of Jewish diamond families. Accounts date it back to Maimonides, the medieval philosopher who purportedly asked his brother, a precious stones trader, to conclude all of his business dealings with a mazal u’bracha.

Furlong’s father, Conrad, was raised Episcopalian, but converted to Judaism five years before hanging out a shingle in the storeroom of Kantor’s building. Initially spurred on by his marriage to Kantor’s daughter, Irene, his conversion ultimately found a spiritual pitch within his daily life.

Today, Conrad Furlong, one of Los Angeles’ premiere diamond setters, dons his pale blue smock each morning to work at a bench just a few feet from his son. The two employ tools as small and precise as those used in the dental field.

Diamond setters — Jewish or otherwise — only teach the business to their sons and sons-in-law. Conrad Furlong was an exception.

Furlong was able to learn the trade by virtue of Kantor’s industry friendships. During his apprenticeship, he was only allowed to look over a setter’s shoulder and could not say or touch anything. To develop his skills, Furlong built a workbench in his apartment and with fake stones and silver mountings, reproduced everything he saw — from memory.

"When my son was born, I went into business for myself," Conrad Furlong said. "Later, I took my six best employees and moved to Hill Street to do only high line [setting, building and designing high-quality jewelry]." His wife still takes care of the bookkeeping.

Aaron Furlong, who also creates jewelry under the name Aaron Henry Designs, received his graduate gemologist degree at the Gemological Institute of America in Los Angeles. He fabricates intricate gold and platinum mountings with torch and solder.

His love for colored stones — emeralds, sapphires and rubies — has earned him design and manufacturing awards from the American Gem Trade Association, De Beers and other industry organizations.

"I first began separating burrs [tiny texture grinders] in my grandfather’s store when I was 7," Furlong recalled. "That was when the industry was only about five or six buildings on Broadway, not the two dozen on and around Hill Street it is today. The diamond dealers would join together after work to drink whiskey," he said. "They’d walk around with parcels of stones worth hundreds of thousands of dollars and do deals in the elevators."

The grandson, who was raised Conservative, takes pride in the Jewish legacy his industry has fostered and in the reputation his family has achieved.

"Things like ‘blood diamonds’ [stones Angolan rebels sold to the diamond trade to finance their terror campaigns] and the harsh checks De Beers imposed on miners years ago to prevent smuggling have made the industry police itself," Furlong explained. "We do background checks on all our suppliers" he said. "And I’ve visited one of our dealer’s cutting centers in India to affirm the working conditions with my own eyes."

To ensure their stones are "clean" or legitimate, the Furlongs belong to the American Gem Society and the Jewelers Vigilance Committee, groups devoted to upholding industry ethics. "Anyone running afoul of watchdogs like the Diamond Council will have a hard time surviving in this business," the grandson stressed.

A diamond’s journey from mine to showroom is a convoluted one. Global conglomerates own the mines and offer site-holders, of which there are about 80 to 120 worldwide, the ability to purchase raw stones, called "roughs."

Site-holders transport the roughs to cutting centers. Manufacturers like the Furlongs buy parcels of cut stones directly from site holders and sell the finished pieces they’ve created from them to wholesalers and retailers. Because the mines for colored stones are less controlled and scattered throughout the globe, supplies come directly from the mines or the cutters.

"If there is a cornerstone of Judaism in this business," Furlong said, "it’s the diamond cutters and brokers. They come from Tel Aviv, New York and South Africa and meet at the Diamond Club down the hall. That group speaks with a unified voice for L.A.’s Diamond District."

Irene Furlong, now in her mid-50s, hasn’t known any other life but gems and diamonds. Her childhood was spent in her father’s showroom, "shooting marbles" with his inventory of pearls.

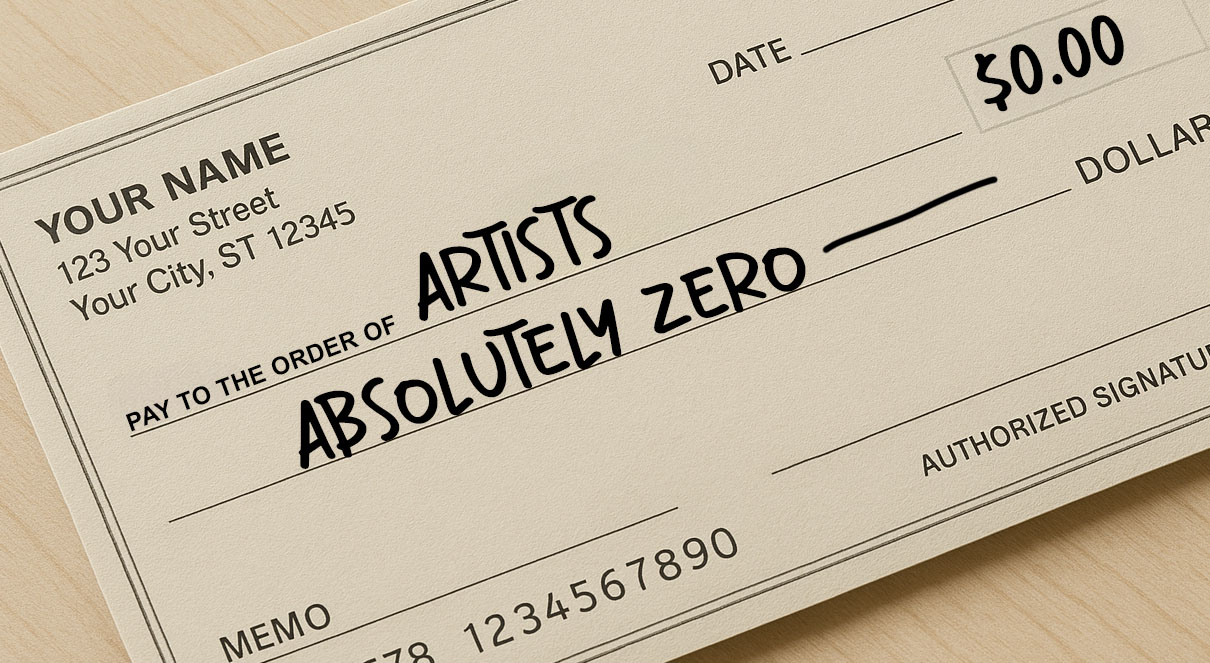

"Everything is done with memos [written receipts for loose stones] these days, and we’ve lost many of the old traditions," she said wistfully.

"I remember one client we had who had a three-band Pavee ring and was stung by a bee," she recalled. "The paramedics couldn’t cut the ring off through the diamonds, so they called Conrad, who takes the jobs no one else can do. He went to the ER and removed each stone from its setting. The whole time, the client’s husband was yelling: ‘Be careful. Don’t damage the diamonds!’"

In a luxury industry that generated more than $42 billion in jewelry and watch sales in the U.S. last year and $54 billion in worldwide diamond sales alone, the Furlongs, like many other diamond industry families, are reluctant to draw too much attention. In Los Angeles’ Diamond District, uniformed and undercover police patrols keep a close watch on area.

"The Jewish immigrants who built this business came from very harsh backgrounds, and were attracted to the beauty of precious stones and gems," Aaron Furlong said.

"They were multifaceted people," he said, smiling at the pun. "As it was in my grandfather’s time, 50 years ago, this business is a blend of instinct, engineering and art."

"It doesn’t matter if it’s diamonds or colored stones," he continued. "The challenge is to build a luxury piece that’s timeless and beautiful. And to conduct your business in an honorable way" — with a mazel und brucha, as Kantor would say.

David Geffner can be contacted

at liturkfilm@earthlink.net

.