The evocative title of “At the Narrow Waist of the World: A Memoir” by Marlena Maduro Baraf (She Writes Press) is a reference to a familiar geographical feature: the Isthmus of Panama. That is where Baraf grew up in the 1950s, and she evokes the time and place.

Baraf has an eye for telling details and an ear for the nuances of language as it falls on the ear. The book opens with her musings on the differences in meaning between English and Spanish that are beyond the powers of the translator. “Tone of voice, a phrase, a snapshot in my mind — this is how my memories began,” she explains. “Judía, with the harsh jota sound, meaning ‘Jew,’ arrived chained to ancient epithets, loathing, and fears, though my Sephardic Jewish family was generally treated with delicacy in a country of easygoing people who lived in a steaming heat that was almost impossible to escape.”

The stories Baraf tells are intimate and intense. For example, her mother suffered from mental illness and was subjected to shock therapy — “the sugar kind,” her uncle revealed, an apparent reference to insulin rather than electrical shock. “For me and Patricia and our baby brother Carlitos,” Baraf writes, referring to the three siblings in the family, “mami was ours, inescapably our mamá.” Baraf goes on to describe the points of connection between a mother and her children in language that soars far beyond cliché. “She was a piece of us, like a nose or budding breasts. When she pressed the fleshy part of her thumb against her teeth — again and again — we were her thumb. ‘Stop, mami!’ we begged.”

Baraf depicts her childhood as alternately rhapsodic and horrific. Her papi buys handmade kites, fashioned of colored paper and bamboo from the boys who sell them door-to-door, and he teaches his children how to “feed the kite air” to send it aloft and keep it there. Yet he uses the same whip — a “handsome wand … finished in lustrous dark-brown leather with long, loose, leather straps at one end” — to discipline both his horse and his son when they displease him.

Now and then, the author widens the lens to capture the origins and destiny of the community to which she belongs. Baraf’s ancestors were expelled from Spain in 1492, moving first to Holland, England, then to the Virgin Islands, finally settling in Panama in the middle of the 18th century. Even so, history and politics remain in the background, and she succeeds in showing us what life was like in glimpses of daily life. “Though we were Jewish, we had a Christmas tree at the front window,” she writes. “But we didn’t have a crèche like my friends did.” Baraf shares a photograph of the “baby-naming dress” both she and her father wore in imitation of the garb their Catholic neighbors used in the christening of their infants.

Baraf depicts her childhood as alternately rhapsodic and horrific… Now and then, the author widens the lens to capture the origins and destiny of the community to which she belongs.

Almost inevitably, America beckoned. Mami was thought to resemble Loretta Young, whose television show beamed into Panama from the U.S.-controlled Canal Zone, which the author recalls as “a little bit of heaven.” A local seamstress sewed dresses from patterns from Vogue or McCall’s, “bodice and skirt quarters printed on thin yellow paper with skipping lines and dots for the pins when making pinzas under the bust (if you had a bust).” Some relatives already had reached the United States, and Baraf’s mother was sent to Massachusetts for psychiatric care because her brother lived nearby. Baraf joined her sister at a boarding school in Pennsylvania. “There was no gold on the streets,” she recalls, but the opportunity to make angels in the snow was magical.

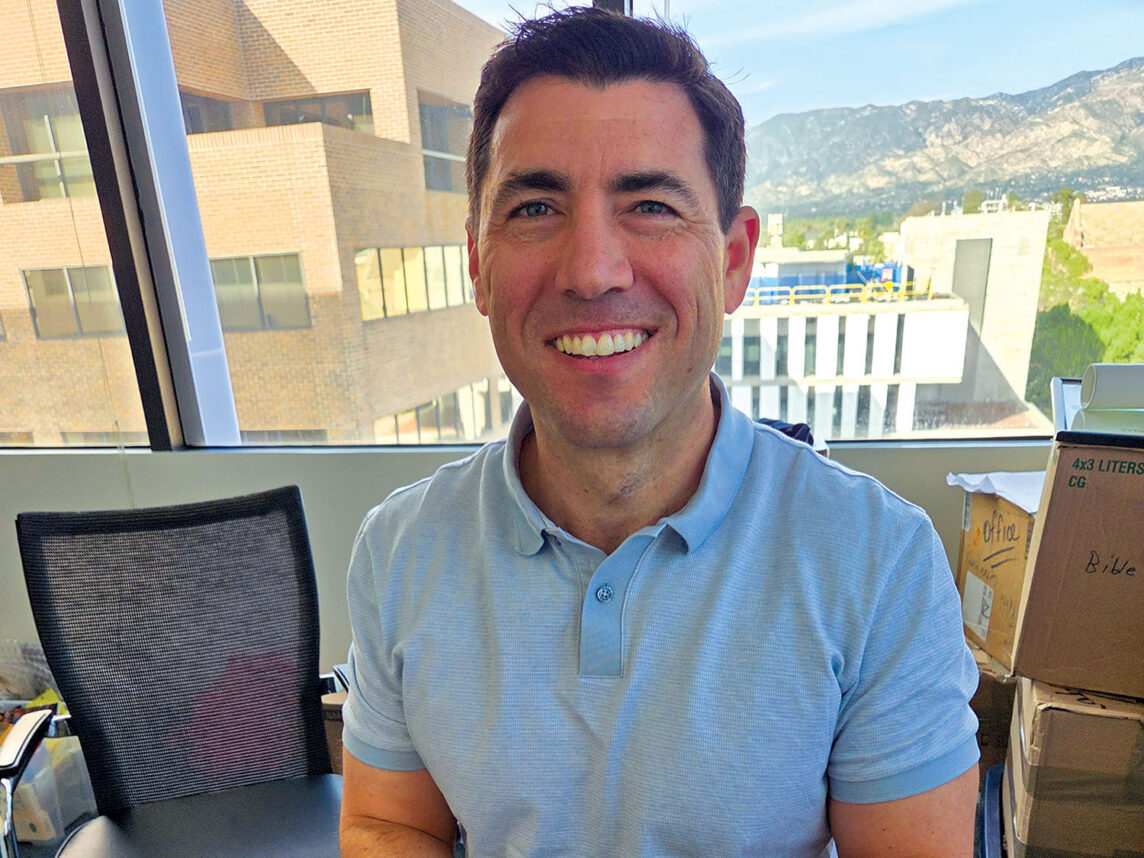

Baraf started her college studies at Occidental College in Eagle Rock, and she pursued a career as a book editor in New York. She returned to Panama to marry her American husband, and she shows him a memorial tablet at Kol Shearith Israel synagogue. Readers see a photograph of the same plaque, and a lump came to my throat as I recognized the last names of her extended family, so many of whom have been introduced to us in her recollections. The author, too, ponders how she is connected to the men, women and children who have entered and passed out of her life.

“I have narrow wrists and pointed shoulders and a long neck,” she muses. “My eyes are brown. Sometimes, they are blue. I have white skin, an inclination to art, to music and emotion.” Her mother, so tortured by mental illness, is “one of the digits, a part of the hand.” But Baraf is compelled to distinguish herself from her mother: “The finger does what it can. It is not like the other fingers, and this makes me take special care. I am family.”

By the end of “At the Narrow Waist of the World,” we have come to know, admire and even cherish its author in a way few memoirists manage to achieve. The point is made in the author’s account of a childhood episode in which her mother imagined the maids in the family home were trying to poison her food. “Etonces pruébalo,” her mother says. “Then taste it!” Baraf writes: “Good little girl that I am, I taste the bitter truth.” And so do her readers.

Jonathan Kirsch, author and publishing attorney, is the book editor of the Jewish Journal.