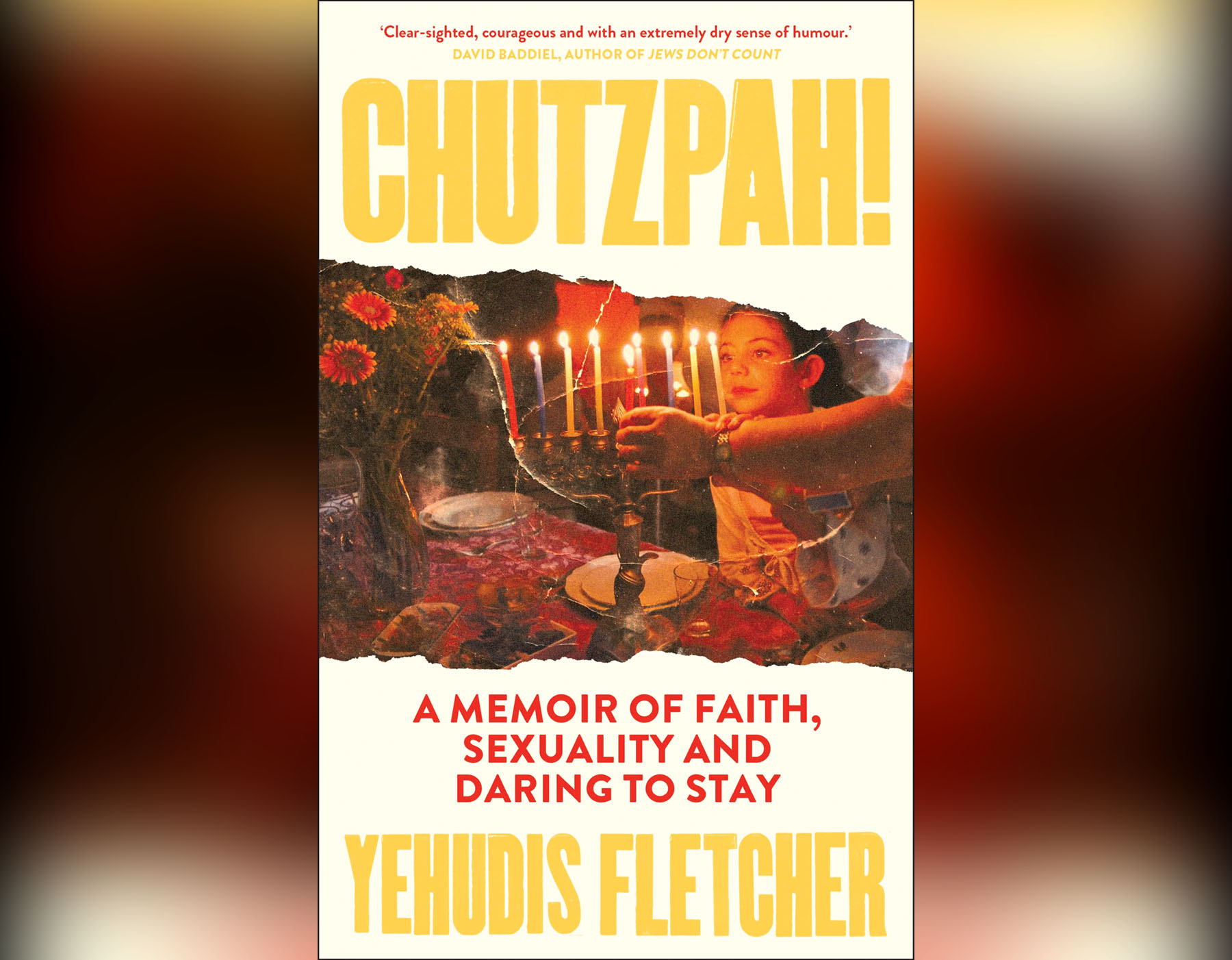

I was recently invited to give a talk, drawn from my book “Women of Valor,” about “off-the-derech” memoirs—stories of people, primarily women, who left their Orthodox Jewish communities and wrote about their experiences. I focused on the element of sexuality that comes to the fore in these memoirs. After the talk, two attendees approached me. She wore a turban, he a kippah. We debated the merits of the film adaptation of Naomi Alderman’s “Disobedience” and discussed Buttmitzvah, a queer Jewish club party held in London once a year (bless their hearts, they invited this middle-aged mom to join them next time around!). Mostly, they wanted to tell me how excited they were about a book I had mentioned in passing, one that was, in many ways, not so different from the off-the-derech memoirs I had been showcasing, but with a crucial difference. It was about a woman, a Haredi lesbian, who didn’t leave; she stayed. At the time, the memoir had not yet hit bookstores, but these two young, queer, Orthodox attendees couldn’t wait to read it.

The memoir is called “Chutzpah,” and the author is Yehudis Fletcher. I had known fragments of Fletcher’s life story before cracking open her memoir. She has been a speaker and an advocate. Years ago, I heard her give a talk at a Limmud festival, and later, I interviewed her about her organization, Nahamu, that she founded with Eve Sacks, the daughter-in-law of the former chief rabbi, to challenge extremism. But the various pieces came together in a memoir that covers much of her life, with a focus on two issues that proved to be challenges to the Haredi family and community in which she was raised, a community in which sexual matters are often silenced: that she was sexually abused, and that she is a lesbian.

Fletcher grew up in Glasgow, a city with a small Jewish and smaller Haredi community. Her father was a rabbi there. When her parents decided to uproot and move to Israel, she struggled to fit in. Alone, she was sent to a school in Manchester, where she boarded with a Haredi scholar named Todros Grynhaus and his family. At the age of 15, Fletcher was abused by Grynhaus. She was not his only victim. Years later, thanks to her testimony, he was imprisoned.

To say that Fletcher’s family was less than supportive when they became aware of the abuse she suffered, and later when she spoke to the police and in court, seems an understatement. Her family worried about her reputation (who would want her for a wife?). Her mother participated in the victim-blaming, asking why she hadn’t locked her door. Of course, a memoir is only one person’s version of history; perhaps her family members saw or remember it all differently. But a general lack of support for someone who fails to look the same, think the same, and act the same, and especially for one who speaks out, is a theme in the book. When Fletcher, after two failed marriages to men, came out as a lesbian, rejoicing in her first chosen romantic relationship, her family seemed to prefer estrangement to acceptance.

Fletcher’s desperate desire for her family’s love is hard to read. But over the course of the narrative she slowly transforms from a needy woman repeatedly struck down for not keeping to her place to a woman who comes to own her sexuality. She takes to the internet to find out about the world around her. She enrolls in a university program to educate herself. She fights to keep her children in Jewish schools. We see how she develops a voice and makes herself known. The reason the people who came to my talk were excited for her memoir is because she has, repeatedly, put herself out there. This memoir will continue that work, and, like many writers of off-the-derech narratives, Fletcher writes for those beyond her community, translating Jewish terms and explaining rituals. “The timing of the sabbath—shabbos, to us—is determined by dusk,” she says, for example, first proffering the “you” version, then the “us.”

Yet this is not an off-the-derech tale. “None of this has ever been about leaving Judaism behind,” she writes. When Fletcher says “G-d wasn’t a belief system, He was the rhythm to our home, our lives,” she is not only talking about her childhood. She still feels this way. Compare that to Shulem Deen, who poignantly wrote: “Losing your faith is not like realizing that you got an arithmetic problem wrong. It is more like discovering your entire mathematical system is flawed, that every calculation you’ve ever made was incorrect.” No matter that Fletcher discovers that she won’t suffer divine retribution for not ritually washing before a meal, or wearing pants, or singing, or driving (something women in her community are banned from doing). Over and over, Fletcher tells us: “My belief in G-d’s existence was never in question.” She adds, “In fact, it was because of my belief in Him that I worked so hard to find the truth behind all the rules that stood between us.” She concludes that many of the rules in Haredi culture are man-made, not dictated by God at all.

“G-d wasn’t a belief system, He was the rhythm to our home, our lives.”

Maureen Kender, a Jewish educator, once said, “I’m not threatening to leave. I’m threatening to stay.” It’s a philosophy that Rabbi Miriam Lorie, the UK’s first woman in an Orthodox rabbinic leadership role assumed as her own, and it’s one that Fletcher does, too. By staying, she might make those who are dedicated to their (man-made) rules angry; but for others, crucially, she is a role model.

Karen Skinazi, Ph.D. is Associate Professor of Literature and Culture and the director of Liberal Arts at the University of Bristol (UK) and the author of “Women of Valor: Orthodox Jewish Troll Fighters, Crime Writers, and Rock Stars in Contemporary Literature and Culture.”