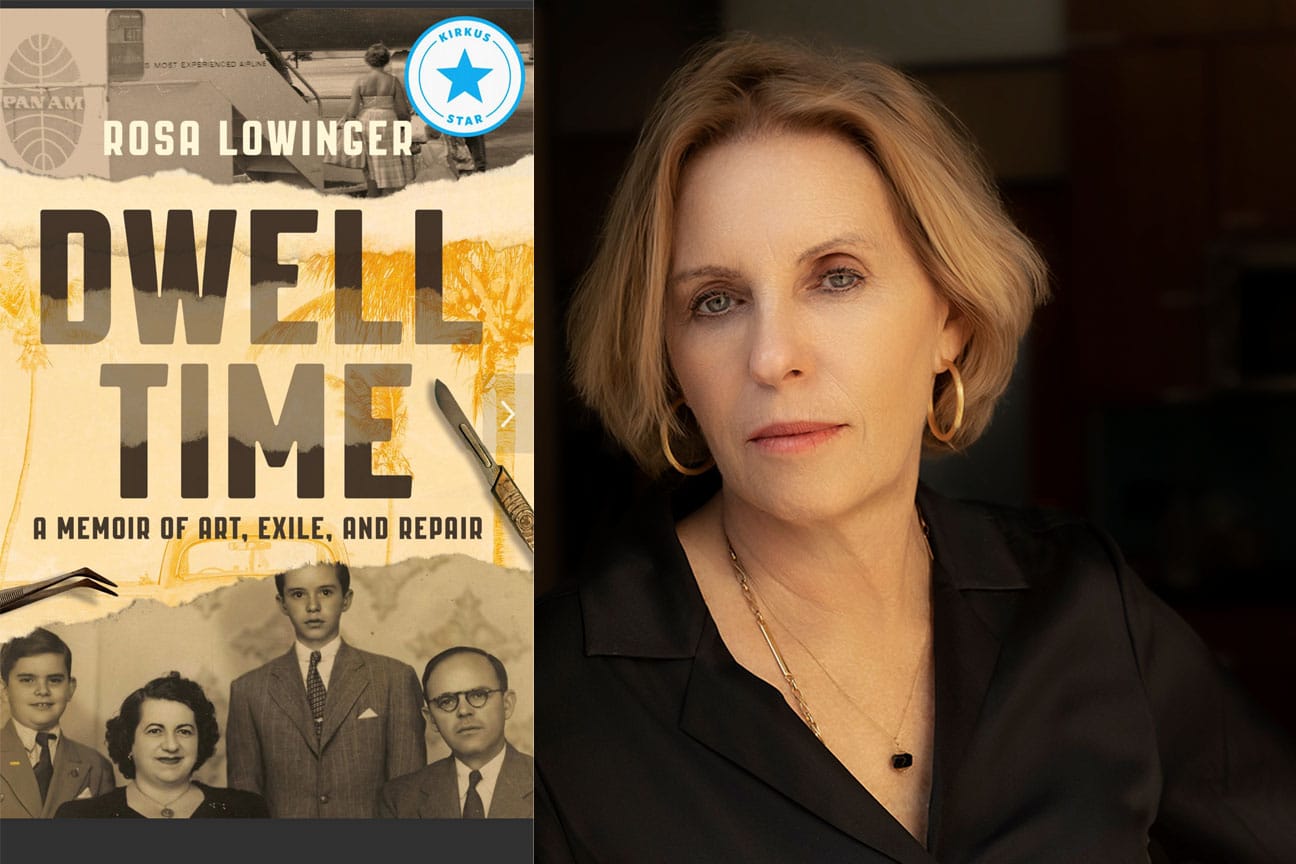

Cuban-born, U.S.-based author Rosa Lowinger is one of the few prominent Latinas in the field of art and architectural conservation.

In her memoir, “Dwell Time,” Lowinger draws upon the methods and materials of art conservation to tell her story. She entwines the details of conserving historic buildings and works of art with her family’s double exile as Jews from Eastern Europe in the 1920s and then Cuba in early 1961.

Lowinger, who came to Los Angeles at age 32, has lived in the mid-Wilshire area for nearly 35 years. It’s a neighborhood filled with houses and materials that hold the city’s history. Plus, she says, holds architectural similarities to her hometown of Havana and adopted town of Miami. All have Mediterranean architecture with decorative tile, mosaics, cast stone and unusual materials that hold their histories.

“During the writing I realized that I have been here almost as long as three generations of my family were in Cuba,” she said. “I began to see how even though I feel Cuban and a native of Miami, it is not surprising that this book came together here in LA, and that my greatest personal transformations took place here.”

The Journal spoke with Lowinger about this very personal and professional endeavor.

In what ways have your Jewish roots influenced your life and career?

As you will see in the book, my Jewish life influenced me from start to finish. My parents fully defined themselves as Jews within their country Cuba and once they came here they identified as Cuban Jews, straddling two worlds and being part of both. In one scene in the book, I recount how I went to Orthodox day school and was deeply moved by the way Shabbat closed the door on chaos every week. I am not Orthodox myself, but when I grew up in a chaotic household with lots of anger and strife, I saw that creating sacred space, where one put all of that aside, was the wisdom of Jewish practice.

When I went to Brandeis, I majored in Medieval art and I wanted to study Jewish illuminated manuscripts for a living. It didn’t happen, but I am a big believer in the value of being part of a community, especially a Jewish one, if that’s what works for you. I love working on Jewish objects. I was part of the Skirball move a few decades ago and I got to work on every single piece in that collection. I also worked on the Wilshire Boulevard Temple conservation as the conservator addressing many of the metals. It’s powerful stuff to work on sacred objects, and the Jewish ones are just closer to my heart.

What do you want people to know about Cuban Jews?

Oh, a lot! First, few of us call ourselves Jubans or Jewbans. That’s an outsider term for us and I find it sort of annoyingly cutsie. I know some Cuban-Jews have adopted the term, but in my experience, it comes from the outside, not from within. That said, I’d ask Ruth Behar, who is the reigning scholar on all things Cuban-Jewish.

Second, our community is varied and deeply Cuban. The most intense strain of Cuban-Jewishness is in Miami, because there, among so many Cubans, our assimilation into Jewish life as a whole has been more limited. Also, people who stopped off in Cuba for a few years on their way to the US are not Cuban Jews. I’d say we are people who spent generations in Cuba and thought of it the same way Eastern European Jews who came to the US think of themselves as American. We are Cuban, and our grandparents never expected to leave our country.

We share a great deal with our non-Jewish fellow Cubans. For example, loving black beans and rice, plantains, even pork. And many of us secretly practice santeria, the Afro Cuban spiritual tradition that comes from Yoruba Ifá and is the primary spiritual practice in Cuba. I know many Cuban Jews who would not dream of having a Christmas tree but carry Santeria amulets (what we call resguardos) in our purses. One of these is my hyper Jewish-identifying mother, as you will note in full technicolor in my memoir.

In LA, I’ve always seen many similarities between the Persian Jews and the Cuban Jews. We were firmly entrenched communities that were suddenly uprooted from our homes and can’t go back. The Persians were more established (for centuries actually) but both communities have a particular way with food, parties, bar mitzvahs, weddings and shorthand expressions.

How does it feel to have something so personal, transformative and educational out in the world?

It’s a bit raw and tender, but it’s also exhilarating. It also seems to dovetail with something in the Jewish zeitgeist right now, at least the progressive strain of it that is so powerful in Los Angeles.

We are looking for paths towards Tikkun Olam. Our best rabbis and thinkers (in particular I’m thinking of my own rabbis at Ikar Los Angeles) are digging deep into those hard questions and coming up with important action items and spiritual work to do to mend the tears in our commonality and human fabric, as well as to right the wrongs of the past.

As for the conservation part, I am especially eager to see the work that we’ve done in Los Angeles featured in a book. Our local conservation community—at LACMA, the Getty, the Autry, and various private practices— does extraordinary work. We are national leaders when it comes to managing triage after fires and earthquakes and our local projects are exceptional. I feature my work on the Watts Towers, Bullocks Wilshire, the Gilbert Silver collection at LACMA and the mausoleum at the Huntington in the book. I want my colleagues to be at my events, to join in the conversation, so that our work is really seen.

People think of conservators as lurking in the shadows or that architects can do what we do; but we are the ones who understand the behavior of materials. We’re the ones who can commune with an artist’s process or the fabric of a building in its totality.

What is the connection between physical and emotional restoration?

There are many of course, some related to the mind-body health connection which I strongly believe in. But that is not my subject here.

In my book I mine the idea that repair is a product of understanding damage. As conservators we approach all of our treatments with a deep dive of trying to understand what we work on. How it was made, what was it used for, and most importantly, how did it get damaged?

Conservators all have a feeling of tenderness towards our “patients.” Even when they’re fussy and give us trouble (the Watts Towers is a notable example of a structure that needs constant attention), we form an alliance with the things we work on that is born of understanding their weaknesses. If we can get there with human beings, then the world’s problems would be solved. If we could truly look into the face and heart of another and see where they broke down, we’d have a world filled with compassion.

Easier said than done, I know, and I’m no Pollyanna. I think about my own mother, who was terrifying and brutal to me as a child, but who acted out of fear because of what had happened to her, and how her own psychological makeup was thwarted by abandonment and poverty. In conservation we take all of those histories into account.

What is the best way for people to move forward in challenging times?

If you are lucky enough to have a good spiritual guide, seek their guidance. But most importantly, find community: a community of compassion, a community of writers, restorers, beekeepers, hikers, painters, crocheters. People who will see you in your wholeness and hold space for your heart. We are social animals and we can’t cut off from each other.

On October 18th at 7pm, Rosa Lowinger will be in conversation with Carolina Miranda, art and design columnist for the “LA Times,” at the Mark Taper Auditorium at the Central Library. Learn more about Lowinger at RosaLowinger.com

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.