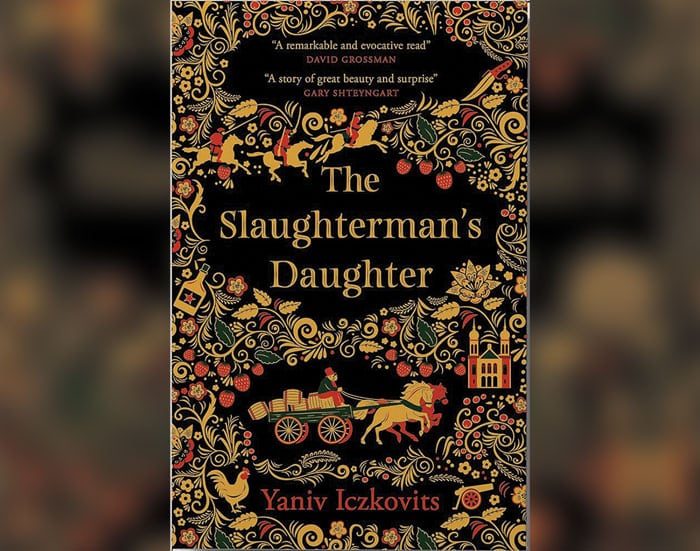

I sat down with Yaniv Iczkovits, author of “The Slaughterman’s Daughter,” an exuberant, picaresque tale of a daring 19th-century heroine, Fanny, and the colorful cast of characters she meets along her journey. I wanted to know if he set out to write a feminist story, who inspired him, and what role his philosophy Ph.D. plays in his fiction. Below, some answers. (This interview has been condensed and edited for space and clarity.)

Jewish Journal: The quest of the hero is traditionally a male genre, so what made you decide to give this quest to Fanny? Would you call it a feminist story?

Yaniv Iczkovits: When I decided to write this story, I knew that the protagonist needed to be a woman. Reading advertisements in newspapers [from 19th-century Russia], it was clear that no man would ever think even think of going on this journey. Because the Jewish tradition is very … it really plays into men’s favor. They could leave their families, and thousands of Jewish men did at that time, and they were not penalized in any way. So— a woman should do this journey.

Yaniv Iczkovits: When I decided to write this story, I knew that the protagonist needed to be a woman. Reading advertisements in newspapers [from 19th-century Russia], it was clear that no man would ever think even think of going on this journey. Because the Jewish tradition is very … it really plays into men’s favor. They could leave their families, and thousands of Jewish men did at that time, and they were not penalized in any way. So— a woman should do this journey.

Whether it’s a feminist…well, I think what Fanny is doing is very similar to what [her brother-in-law] Zvi-Meir did. He left his family, and he’s supposed to be the villain because he left them, and they’re very poor. But she is doing the same to her family, even though she’s doing it for a more righteous cause.

I’m not sure whether it’s feminist, but I do think that she is like: OK, I know that I’m going to somehow damage my children, but yeah, I’m going for it. Why not? If men can do it, why not me? [laughs] It’s almost wishful thinking or even a prayer that more women will take control of things because we all see what’s going on with men leading—politically, religiously, socially—so wo-men taking over, it’s basically one of the main solutions that I can offer humanity.

Fanny is different [from the male characters]. Whenever she acts with violence, it’s almost because she doesn’t have a choice. She has a sense of doubt, remorse, thinks maybe I’m wrong and maybe I shouldn’t have gone through this journey, whereas for the men, violence is almost the nature of things, the world has to be manipulated by violence and power.

JJ: Who are the writers that inspired you?

I feel like Israeli literature is very heavy. Humor is not one of its merits. It’s not plot driven but, usually, psychological. So, I was looking for something else. Yiddish writers were always my favourite.” –Yaniv Iczkovits

YI: I feel like Israeli literature is very heavy. Humor is not one of its merits. It’s not plot driven but, usually, psychological. So, I was looking for something else. Yiddish writers were always my favourite. Sholem Aleichem and Mendele Mocher Sforim and Bashevis Singer and Isaac Babel and Zalman Shneour…this is how I started to write the book. I was wondering what Sholem Aleichem read when he woke up in the morning, like what sort of newspapers did he read? Because I thought: OK, Sholem Aleichem, he lives in the shtetl, conditions of life are hard, and nevertheless his fiction is full of humor and sarcasm and irony. So, what were his sources of inspiration? This is how I came to Hamagid and Ha-melitz [the first Hebrew newspapers] and found advertisements of these desperate women.

There is something in the Yiddish that was lost in Hebrew, not only the humor. It’s a Weltanschauung, a way of seeing the world. You can laugh at the world, make jokes, complain, but in the Yiddish culture, you don’t have the power to change it, so you need to accept it. Accept things as they are and do your best to not be in despair when things go wrong. We always have the dilemma of doing something to change, like a tikkun — you know the book in Hebrew is called Tikkun [repair, as in Tikkun olam, repairing the world]?

The problem that I think the Yiddish writers had is that when they depicted characters that were not Jewish, they were stereotypical. You see it in Berdyczewski and Sholem Aleichem, and also in Russian writers like Dostoevsky and Tolstoy, when they had Jewish characters, which verge on antisemitic. When I wrote (the character) Novak, I read Gogol, Dostoevsky, Turgenev…it was important for me to try to build Novak like a real Russian character, not a stereotypical stupid goy.

The main challenge was language. It all started with: How would I write it? In what language would I write this book? At the end of the day, the solution is a mixture. When we have the shtetl scenes, they’re more influenced by Sholem Aleichem and Bashevis Singer. In the Crimean war, I tried to be more like “War and Peace”; for the taverns, it’s Gogol.

JJ: Can you tell me about your research process?

YI: It was about finding the right resources. There are a lot of books about the shtetl, but not many books about daily life, so a huge inspiration was Eva Hoffman’s book “Shtetl.” When I wrote about the Crimean War, I wanted books about how soldiers felt sitting in the trenches. What did they eat? I found diaries that led me to other diaries that led me to other diaries. I don’t think I read one book about the Crimean War to learn the political or military aspects.

I was very troubled about the geography, as well. I was writing about swamps and rivers and trees and animals, so I went to Belarus before the book was published. To my surprise, when we landed in Motal, it looked very much the same as the shtetl of the 19th century. Laundry in the river, restrooms in the backyard …many things hadn’t changed. It was good that I went there, and I fact-checked the distances, but the most important part was seeing those shtetls without Jews. You can feel something missing. The absence is present.

JJ: Is that because you know?

YI: I don’t think so. There’s something there, and I’m not talking about the abandoned synagogues or people telling you “This was a Jewish house.” Something in the atmosphere makes you feel the absence.

JJ: I saw that you were in another life you were a philosopher. What kind of philosophy did you study? Is it embedded in your fiction?

YI: I studied philosophy of language and wrote a book about Wittgenstein. When I started writing fiction, the bon ton was: if you have something to say then write philosophy or an essay, but fiction is showing and not telling, it’s about an emotional process. If you want to say something about the world or ideas, then it needs to be reflected in the characters, plot etc. I accepted this in my first and second books, but then I was thinking that the novels I like to read most are not like that. I cannot escape from my philosophical urge to say things, like Umberto Eco, or José Saramago, writers I adore. Also, I know that the bon ton is to be minimalist, but I can’t help it, it’s one of my pleasures to go into the story and substories and have more characters.

Indeed! And one of my pleasures to read! At the end of our conversation, Iczkovits told me what he’s working on now: a novel about three friends from Transylvania who, in search of a missing sweetheart, return to their origins, retracing, in reverse, their deportation;, and a television adaptation of Isaac Bashevis Singer’s “The Slave” (presenting a “lost world,” much like “The Slaughterman’s Daughter”). I can’t wait for both.

Yaniv Iczkovitz will be the Scholar in Residence at Temple Beth Am on Feb. 16-18. For more information, visit: https://www.tbala.org/learning/scholar-in-residence-weekend/

Karen E. H. Skinazi, Ph.D, is Associate Professor of Literature and Culture and the director of Liberal Arts at the University of Bristol (UK) and the author of Women of Valor: Orthodox Jewish Troll Fighters, Crime Writers, and Rock Stars in Contemporary Literature and Culture.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.