The title is provocative, deliberately so, mistakenly so. The book is alarming, properly so, sadly so.

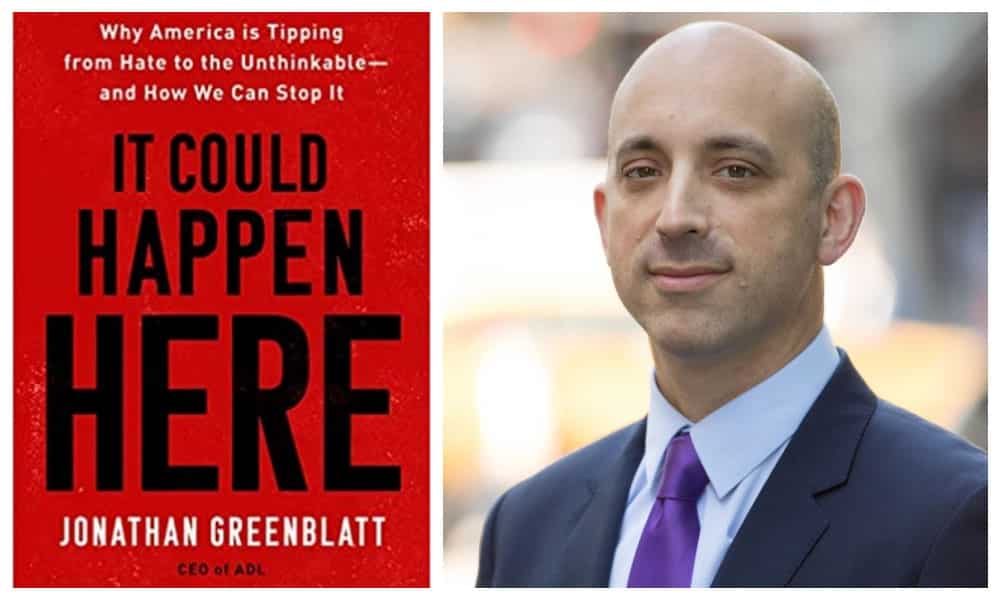

When the CEO of the Anti-Defamation League [ADL], one of the oldest, most distinguished, and most responsible of the Jewish defense agencies, warns us on his book cover that “America is Tipping From Hate to the Unthinkable” and that “It Could Happen Here,” attention must be paid.

“It” is every Jew’s nightmare. No Jew requires an explanation. “It” is the Holocaust. “It” evokes the Holocaust by bullets, the killing fields of German occupied Soviet Union where Jews were slaughtered, often within the vicinity of their homes. The killers were either special mobile killing units, the Wehrmacht [the German army], Axis armies, local gendarmerie, native antisemites, or even neighbors who sought to murder and then inherit their property and their possessions.

“It” evokes trains waiting in towns and cities to deport their Jews to death camps where assembly line factories of death were created to murder the Jews and recycle their possessions and even their bodies into the Nazi war economy.

However bad conditions are in the United States at this trying moment—and I don’t want to minimize for a moment the hatred I witness in our society, the fragility of our democracy, the polarization of our politics, the violence of mass shootings and the venom of our discourse—the United States is not Nazi Germany, not by a long shot.

But that should not be a source of consolation to any American.

Jonathan Greenblatt is a man to be taken seriously, and so it is unfortunate that in his zeal to draw the attention of his readers and to warn them of what he sees, what he experiences day in and day out in his important, dare one say, indispensable role, he goes to a somewhat irresponsible extreme. Jews, not only Jews, but Americans of all stripes, should be alarmed, but they should not be Holocaust-level panicked.

He surely knows it: Elsewhere in the book he writes: “No expert we spoke with argued that genocide, a hate fueled civil war, or some other breakdown of American society was imminent or even likely.” I concur—still, conditions are deeply disturbing.

So permit me to divide this review into two parts, one to consider what Greenblatt says with such authority and such clarity and the other to assure readers that we are not living at a moment of an impending Holocaust, which should not be confused with the notion that we are not living in a terrible, dangerous hateful time where the turmoil of our society should upset, disturb, alarm, or challenge any thinking person.

A word of history may be in order. What else can the reader expect of this reviewer?

Antisemitism differs with regard to its source—religious, political, social, economic, or racial.

Antisemitism differs with regard to its goal. Religious antisemites seek conversion of the Jews and the end of Judaism. Political antisemites want to reduce the political influence of Jews or, at its most extreme, to expel the Jews and to deny them the rights of citizenship, the right to live among us. Social antisemites want to marginalize the Jews, sideline them from contact with non-Jews in what used to be called the “five o’clock shadow”—no informal relations after hours, no Jews in our clubs, our bars, our golf courses, our neighborhoods and certainly not in our homes. Nazism represented racial antisemitism, defining Jews biologically—not by the identity they affirmed, the religion they practiced, the traditions they held sacred, but by blood. Their goal was at first elimination, and later what was called in “Nazi speak” extermination, which we may call annihilation.

Antisemitism differs in the intensity of the hatred of the Jews. There was a seamlessness to Nazi antisemitism as a national priority from the first of Hitler’s rants in 1919 to his last will and testament. What has made Jews less vulnerable historically in the United States is that the Jews were never on the top of the list of people to be hated, never the first target for venom. They still are not. Let me not compile the list of those who are hated before the Jews. Suffice it to say, it is best not to be the first or second target.

And antisemitism varies according to the stability of society. It is an axiom; the more stable a society, the more secure its Jewish population. And the United States in 2022 is not a stable society. There is an ongoing health crisis, an economic crisis, a crisis of democracy, truth, polarization, the legitimacy of institutions including religious, government, universities, schools, and courts, a demographic crisis. The list can go and on.

Antisemitism varies according to the stability of society. It is an axiom; the more stable a society, the more secure its Jewish population. And the United States in 2022 is not a stable society.

Greenblatt understands that the internet is a megaphone, and the social networks mean that haters and hatred cannot be quarantined. There is a significant support system for haters whose views are reenforced by what they read, with whom they text, with those whose posts they share.

Greenblatt’s book is balanced. Although he served in the Obama administration, and therefore one can reasonably assume that he is a Democrat, he is willing to call out the anti-Zionist progressives or Farrakhan supporting leftists without hesitation or apologies. He is willing to attack cancel culture, especially when directed against Zionists on American campuses, willing to call out the Squad. His advice is sanguine: Let those of the left critique leftist antisemitism and those on the right hold their own accountable.

As CEO of an organization whose membership and supporters are diverse, he does not shy away from his critique of the Trump administration and of the former President himself for unleashing hatred and for cuddling antisemites and white supremacists even as they were supportive of Israel.

The strongest part of the book—alluded to in the book’s subtitle (“and how we can stop it”)—is Greenblatt’s prescriptions for action, coalition building and calling out hatred. He is unabashedly determined to protect the safety of Jews, but not Jews alone for he understands that “America could not be safe for Jews unless it is safe for all people.”

The strongest part of the book is Greenblatt’s prescriptions for action, coalition building and calling out hatred.

He understands antisemitism in the context of societal hatreds and as a global phenomenon. Social change and instability, political unrest, mass unemployment the influx of refugees, the pandemic and wars intensify hatreds and fuel antisemitism. These conditions are made worse by a demagogue who riles up passions, speaks untruths and arouses extremists.

Greenblatt also understands the roots of the chant “Jews will not replace us!” in the fear that a dominant ethnic group has when it loses its majority or dominant status. In the post-World War II world and most especially after the Civil Rights struggle of the 1960s, the United States became a more open, more pluralistic society. Jews were more welcome, glass ceilings were broken, and women and Black people were included. Jews in fact thrived, and so white Christian male dominance was challenged.

Ironically, businesses have adjusted well to the new reality; so too has the U.S. military. Both understand that to achieve their goal, a diverse force must work in harmony toward that common goal. They must pull together and not tear the organization or country apart.

Occasionally Greenblatt overstates his case. He describes one incident as “a mob waving pro-Palestinian flags attacked a group of Jewish men as they ate dinner in a Los Angeles restaurant.” Still, he is far more measured than the prominent Israeli columnist Caroline Glick, who described an event during the Black Lives Matter protests as a “pogrom” in Los Angeles and then castigated the community for its underreaction, as if she were the great Hebrew poet Chaim Nachman Bialik City of Slaughter responding to the Kishinev pogrom.

There is a curious, unfortunate omission as Greenblatt distinguishes between legitimate criticism of Israel and antisemitism but does not sufficiently explain how. When IHRA and the Jerusalem Declaration have different and divergent definitions of antisemitism, Greenblatt should have weighed in more deeply on the matter.

He is willing to tell us good news. ADL has conducted a longitudinal study of antisemitism in the United States for generations. In 1964 the percentage of Americans holding antisemitic views was 29%; in 2020, the percentage was but 11%. Yet in 1964 antisemites were reluctant to express their antisemitism, and even more so to act on it. Self-restraint was common: “You may think it but don’t say it.” Today expressions of hatred can be a badge of honor, a mark of authenticity. Yet he notes a tenfold increase in reported antisemitic events within the past five years alone, some of which—but surely not all—he clearly attributes to better reporting.

Religious antisemitism is on the decrease. Christianity has been overtly repentant, more dramatically if quietly so. And there is some evidence that American Muslims have begun to understand that civility in interreligious life is a mark of good citizenship and allows for minority religions to flourish, something Jews learned generations ago.

Greenblatt understands that how a community responds to acts of hatred is important. It can isolate the hater and allow the forces of civility and decency to triumph. Such was surely the case in Pittsburgh after the Tree of Life murders when every facet of society joined together, from government to religious leaders, from sports teams to civic leaders, in acts of solidarity. The aftermath made Pittsburgh stronger and increased intercommunal solidarity.

Greenblatt has been courageous in the battles to get social media to accept responsibilities for the venom that is perpetuated on their sites and reports on his battles with Facebook, his encounters with Mark Zuckerberg and with Fox News, among others. He is candid as to the reasons that ADL and other anti-hate groups have been less successful. There has been no economic punishment for hosting hate speech. The profits are huge.

Greenblatt believes that all of us are responsible for fighting hate in everyday life. He has a skill for condensing into memorable phrases what must be done: Speak up, share facts, show strength. We must mobilize government and religion, create a sense of safety, learn more, complicate thinking, take action.

As Greenblatt clearly demonstrates in this book and as is manifestly apparent in our daily news reports, there is much work to be done and ADL will be there to do it. One comes away from the book with a sense that its leader is responsible and responsive, committed and caring. He understands the problem. That is a good start.

Michael Berenbaum is a Distinguished Professor of Jewish Studies and Director of the Sigi Ziering Institute: Exploring the Ethical and Religious Implications of the Holocaust at American Jewish University.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.