When Doors guitarist Robby Krieger was 19, he went to a Chuck Berry concert at the Santa Monica Civic Auditorium. He was blown away by Berry’s energy, stage charisma and, of course, the sounds Berry coaxed from his red Gibson guitar. The very next day, Krieger, who was playing an acoustic guitar at the time, traded it for a red Gibson — the same model as Berry’s — and his life as a musician was never the same.

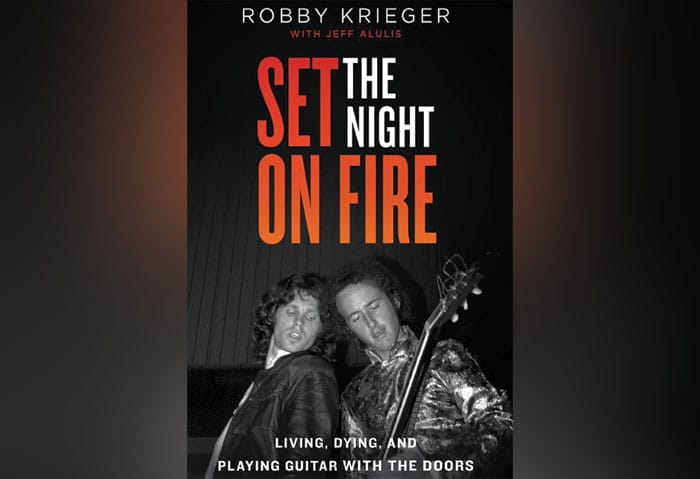

In his new memoir, “Set the Night on Fire: Living, Dying, and Playing Guitar With the Doors,” Krieger details his story and that of the Doors, from his early years to “The End” and beyond. He writes about growing up in Pacific Palisades and how his parents hid their Jewishness from their WASPy neighbors. He went to Hebrew school with his twin brother Ronny, but they goofed around so much that they got kicked out and never had bar mitzvahs.

That was around the time that Krieger first started playing the guitar.

“Once I picked it up, I almost never put it down,” Krieger writes. “And my theory about the guitar being the key to coolness was proven correct: everyone at school suddenly became my best friend so they could get their hands on my Juan Pimentel acoustic [guitar].”

Krieger takes the reader through a litany of wild adventures and stunning stories of rock stardom between 1965 and 1973. From “Light My Fire” to “Roadhouse Blues” and “L.A. Woman,” Krieger is constantly exposed to Doors’ frontman Jim Morrison’s absolute disgust with authority; he explains how it stemmed from Morrison’s strained relationship with his Navy officer father. In the times when Morrison was at his lowest, Krieger’s father stepped in to help his son’s troubled bandmate.

“My dad was the exact opposite of Jim’s dad in terms of being caring and supportive,” Krieger writes. “When my dad spoke to Jim out of genuine concern, Jim listened.”

Morrison’s antics routinely kept Krieger and his bandmates guessing what he might be up to next. In 1967, the Doors were about to perform for a taping of the TV show “Malibu U,” hosted by Ricky Nelson. Morrison didn’t show up.

“After a while we faced the reality that Jim wasn’t coming, so we played ‘Light My Fire’ while my brother Ronny faced away from the camera and did his best impersonation of Jim Morrison’s back,” Krieger writes. “Can you imagine Mick Jagger not showing up for a TV taping and the Stones filming Keith Richards’s brother from behind instead?”

Krieger takes the reader to the Doors’ songwriting sessions, concerts at the London Fog , Gazzari’s and Whisky a Go Go. They would tour around the world, but remarkably, did not play at Woodstock in 1969.

Morrison died at age 27, ending the classic Doors line up after only six years. Krieger discusses the ensuing infighting and band politics that he endured as a short-lived trio with the remaining Doors: keyboardist Ray Manzarek and drummer John Densmore. There would be decades of lawsuits and disagreements with Morrison’s estate and each other that soured their relationships.

Krieger’s music career would continue, though. He and Densmore played together as The Butts Band and he released a solo album called “Robby Krieger & Friends.” He did eventually perform at Woodstock, albeit in 1999. The trio reunited for a few special occasions, including for their induction into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame in 1993, with Pearl Jam’s Eddie Vedder filling in on vocals. In 2012, they toured as “The Doors of the 21st Century,” with the Cult’s Ian Astbury on vocals.

Krieger sets the record straight in “Set the Night on Fire” on several points of dramatic license taken in Oliver Stone’s 1991 film, “The Doors.” He also puts an end to a lifetime of rumors circulated by fans as to why Krieger showed up on “The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour” TV show with a painfully obvious black eye.

But even without Morrison, Krieger had his own hijinks. In 2012, when he was 66, Krieger and Manzarek were in Israel for a show. At the Church of the Holy Sepulcher, Krieger asked the tour guide if he could “lie in the same spot to see if [he] could feel some Jesus vibes and experience what being resurrected as the Son of God might feel like.”

Before leaving the Old City, Krieger put on a yarmulke and said a prayer at the Kotel for Morrison.

The tour guide obliged and Krieger laid down on the stone. After a moment though, guards forcibly dragged him out of the holiest site in Christianity. But before leaving the Old City, Krieger put on a yarmulke and said a prayer at the Kotel for Morrison.

He takes a deep look back at his relationship with his parents, and to this day, Krieger feels fortunate that he had parents who loved music and art. “Considering that my mom was one of the first people to encourage me to play music, I find it fitting that she happens to be buried in the same mausoleum (Hillside Memorial Park in Culver City) as one of my biggest musical influences: Mike Bloomfield from the Paul Butterfield Blues Band,” he writes.

Krieger’s book is one of the most entertaining music memoirs in recent years. He is just as sharp at writing on paper as he is at working the fretboard. “Set the Night on Fire” is an enjoyable, witty and fast-paced 400-page greatest hits album of memories and reflection of a life and career well-lived. He was born Jewish, yet he reflects on his existence as one of music’s most revered guitarists with a non-denominational spirituality, positivity and gratitude.

In the final pages of the book, Krieger writes: “When I see a video of some little kid with inexplicable natural talent, it reinforces my belief that we carry our best traits into our next form of existence. When I see a young girl painting lifelike images in oils with uncanny skill: that’s my mom. When I see a young boy sink a putt that most pros would miss: that’s my dad. When I see an even younger boy sink an even tougher putt: that’s my brother. When I see a child prodigy playing a spellbinding piece of classical music on piano: that’s Ray. When I see… well, to tell you the truth, I’ve still never seen anyone quite like Jim. But I keep looking.”

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.