The nameless young Israeli soldier whose voice we hear in “The Drive,” a novel by Yair Assulin (New Vessel Press), is driving on the coastal highway with his father and thinking back to his tour of duty in the Israeli army. Nowadays, we hear a lot of talk by politicians about the ambitious plans that the rank-and-file soldiers of the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) will be responsible for carrying out, but we hear almost nothing from the soldiers themselves. “The Drive,” however, gives us a rare glimpse into their hearts and minds.

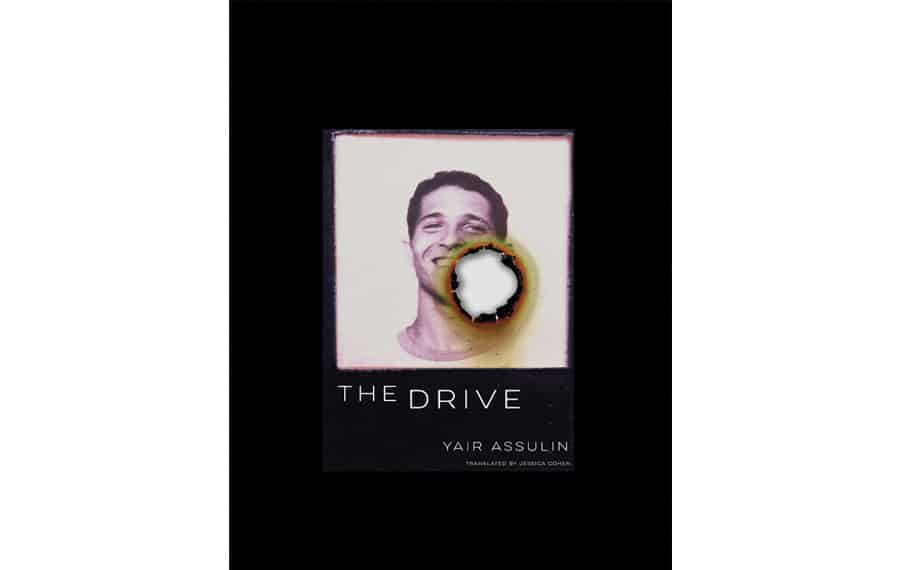

Assulin, born in 1986, is a columnist for Haaretz. “The Drive” was first published in Hebrew in 2011 and won several prizes, including the Sapir Prize for debut fiction. The English translation by Jessica Cohen, a winner of the Booker Prize, was supported by the Israeli Fund for the Translation of Hebrew Books, an arm of the Ministry of Culture and Sport.

The soldier thinks back to the last conversation with his girlfriend before he reported for duty. Ayala proposed they break up before the army forcibly separated them, speaking in the “Tel-Aviv-New-York-intellectual tone that she was so fond of, like a character in a Woody Allen film, always in a confident voice, the kind used by someone who knows everything.” He recalls how “just to see her eyes fill with worry,” he “described to Mom how the notification officer would knock on our door at two a.m. to inform them of my death.” And he muses on one especially dire moment when “I honestly could have cocked my weapon and shot myself.” So we are not surprised to learn that “the word ‘army’ now makes me nauseous.”

Diagnosed with asthma, he is transferred from a combat post to a base near Nablus. “It wasn’t dangerous, I know,” the soldier concedes, “not dangerous like driving in the middle of the night in a black Audi to arrest a wanted person in a village, or like sitting at a lookout post in the middle of nowhere when someone could put a bullet through your head at any minute, or like actually fighting in Lebanon or Gaza. But for me, it was soul-crushing.”

Assulin’s narrator is a complex and believable human being rather than a character whose role is to criticize the army’s role in Israeli identity and policy.

Surely not every soldier in the IDF — or any other army, for that matter — is quite as tortured as the nameless soldier in “The Drive.” For him, the army is a Kafkaesque machine for eradicating the identity and free agency of the men and women in uniform. “Sometimes I had the feeling,” he tells us, “that in fact I hardly existed, that I had to do everything for someone who did everything for someone who did everything for someone, and sometimes I had the feeling that the ladder never ended but merely branched out endlessly and reeked and grew mold and became caked with mud.” Indeed, all of these recollections occur to him as he drives with his father to an appointment with a military psychiatrist, and we are tempted to regard him as a man who suffers from mental illness rather than a principled critic of the IDF.

“Stop your nonsense already,” his father says, and some readers will be tempted to agree with him. “You understand that without the IDF, this country could not exist.”

The author has an answer to the question. “But how does it exist now?” the soldier replies. “It has laws requiring eighteen-year-olds to enlist, it takes their best years, all their dreams, it destroys their souls, teaches them that what matters is cheating and stealing and trampling and cutting corners and occupying and winning. Is that what a state should teach people at this age?”

Then, too, Assulin’s narrator is a complex and believable human being rather than a character whose role is to criticize the army’s role in Israeli identity and policy. Raised as an observant Jew, he affirms that “one could say that I only found God in the army …, of all places, among the dirt and the hypocrisy and the human foulness He created.” But he is also uncomfortable with what the IDF is asked to do in the West Bank, and the author pointedly uses that term as a place name. Significantly, he turns to a military psychiatrist rather than an army rabbi for rescue, but he recites Psalms while waiting to see the shrink.

“When I first got to the base, I was the religious soldier who was always going to prayers,” the soldier says of himself. “Then I was the one who kept crying to the commander, the one who kept asking questions, the one who cared about honesty and truth and made a point of correcting people’s grammar, the one who read biographies of Heine and Yonatan Ratosh and asked anyone who said they liked music whether they liked Bob Dylan and Leonard Cohen, and if they said yes, something lit up in my eyes.”

At the same time, however, Assulin insists his fictional character embodies a deeper malaise in Israeli society. If he is right, it’s something that is rarely mentioned in the public conversation about Israel in the United States. “I’d always known that the whole business with the army and values and defending your homeland was a big show,” the soldier insists, but now it is “very clear to me, clearer than all the times I had considered it previously, that no one really believed in those lofty concepts, and that all the talk about protecting the homeland and giving back to the country was the empty rhetoric of people seeking respect.”

“The Drive” is a purposefully uncomfortable tale. To be sure, Assulin is an assured and accomplished writer, and his short novel captures and holds our attention, roils our emotions, and challenges our comfortable assumptions. Above all, the author is fully aware he has created a character who is both troubled and troubling, and he makes no apology for it.

Jonathan Kirsch, author and publishing attorney, is the book editor of the Jewish Journal.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.