Among Esther Safran Foer’s distinctions is that she is the matriarch of America’s first family of Jewish-American letters. Her three sons are Jonathan, Franklin and Joshua, each one a best-selling author. Now that she tells her own story in “I Want You to Know We’re Still Here: A Post-Holocaust Memoir” (Random House/Tim Duggan Books), we see for ourselves where the literary DNA of the Safran family originated.

According to her birth certificate, Esther Safran was born Sept. 8, 1946, in a German town called Ziegenhain. “It’s the wrong date, wrong city, wrong country,” she reveals. “I am the offspring of Holocaust survivors, which, by definition, means there is a tragic and complicated history.”

Foer discovered her father was married to his first wife and had a daughter when Nazi Germany invaded the Soviet Union, and the Germans murdered both the wife and daughter. To put a name to her long-lost half-sister, she hired researchers in Ukraine and an FBI photo analyst in the U.S., and conducted online DNA searches, but the efforts were unavailing. Even Jonathan Safran Foer’s journey to her father’s supposed birthplace in Trochenbrod, Ukraine, which inspired the novel “Everything Is Illuminated,” failed to confirm any facts about her father or his firstborn daughter.

“Of the person closest to me killed in the Holocaust,” she writes of her half-sister, “I had not one detail, not a name, not a picture – not one piece of memory.”

The success of Jonathan’s novel ultimately prompted Esther to undertake a firsthand investigation of her own. “Like the character in Jonathan’s novel, I armed myself with maps and photographs and eventually boarded a Lufthansa fight to Ukraine in 2009,” she explains. “I set out to let my ancestors know that I haven’t forgotten them. That we are still here.” As it turns out, she succeeds magnificently in her mission.

“I set out to let my ancestors know that I haven’t forgotten them. That we are still here.” — Esther Safran Foer

Foer describes in rich detail the lives of her maternal relatives and even the circumstances of her mother’s first romance, but her father’s biography required years of arduous and frustrating research. “The more I learn, the less I know,” she writes. Thanks to the meticulous record-keeping of the Germans, however, she is able to state with precision that 20 men from Einsatzgruppe C arrived in Trochenbrod Aug. 9, 1942, and started to shoot the Jewish men, women and children who lived there. At the end of the aktion, only 60 Jews remained alive. Among those who managed to escape was her father, who had been sent to a ghetto in another town.

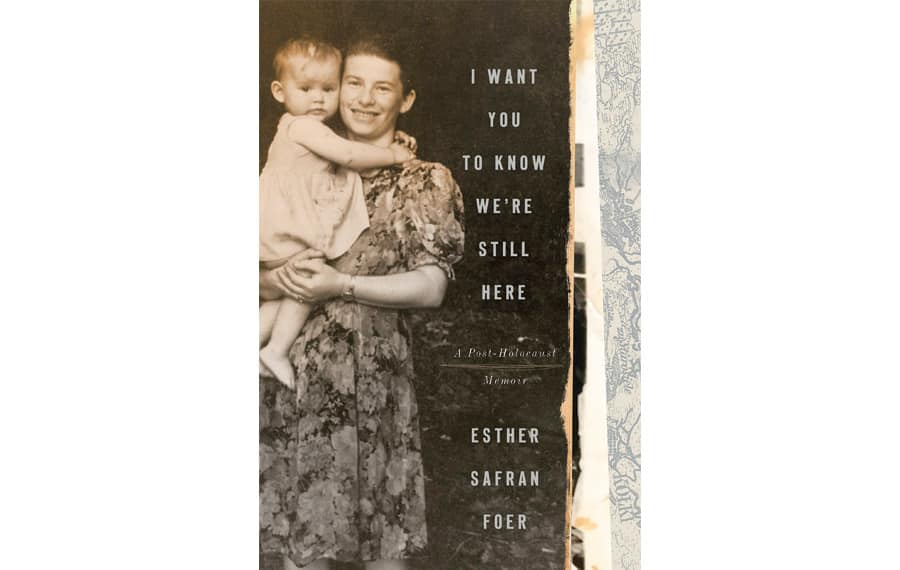

A few days before the defeat of Nazi Germany, Foer’s mother and father were married in Lodz. Even though Foer possesses their ketubah, the date of the wedding is yet another mystery, although she discovered she was born in Lodz on March 17, 1946, and that she was named for her “two murdered grandmothers,” Esther and Brucha. A family photograph reveals where Foer and her parents ended up — a DP camp in Germany. By 1949, they reached America, and her father died there five years later.

As she grew up, Foer quickly realized her father’s wartime experiences were something not to be talked about. “His death became part of the family canon of unspeakable stories that were to remain buried in the past,” she recalls. So dangerous was the subject that “I don’t remember saying my father’s name out loud after he died.” Even the cause of death was a mystery Foer only solved years later when she came across the letters he left behind, all written in a combination of Yiddish and English the family called “Yidglish.” As Foer now understands, even though the suffering and loss were never mentioned, their experiences distorted not only the lives of her parents but her life, too.

“I found myself rebelling against my mother’s habits of deprivation,” she recalls. “Who could blame her, this woman who once stole potatoes and hid them in pockets of her pants to survive? I, in turn, reacted to her behavior by adding a little too much extra everything. I wanted to embrace life, not to scrape by, not to live in the shadows.”

At moments, Foer’s memoir strikes sparks of humor. During the chaotic days after the war, Foer’s mother was forced to deal with a flirtatious fellow passenger on a train to Kiev, but her concern was not a matter of propriety; rather, she was worried he might detect the gold coins she was smuggling under her clothing. More recently, her mother joined Jonathan on a national television broadcast to teach Martha Stewart how to make matzo balls. “In the green room, before the show began, she told the staff that she had survived Hitler, only to have them quip, ‘Well, then, you can survive Martha.’ ”

Above all, however, Foer’s book is an intimate detective story, full of twists and turns, as the author digs ever deeper into her father’s past and draws ever closer to the moment of truth. While visiting the site of the mass murder that took place in Trochenbrod, someone shows her a Russian translation of Jonathan’s best-selling book. But we are never allowed to forget that Foer’s memoir is an account of

real life, and unlike the fictional character in Jonathan’s novel, Esther Safran Foer ultimately comes face to face with the

forbidden facts she sought to retrieve

from history.

To borrow a phrase from the title of her son’s novel, everything is illuminated in the pages of “I Want You to Know We’re Still here.”

Jonathan Kirsch, author and publishing attorney, is the book editor of the Jewish Journal.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.