In August 1978, El Al stewardess Yulie Cohen Gerstel stepped off the bus at London’s Europa Hotel and saw a man hatefully staring at her.

“I think he’s going to start shooting at us,” Gerstel, now 46, told a supervisor.

Seconds later, she was cowering behind a car while the man and an accomplice opened fire on the rest of her El Al flight 016 crew. Shrapnel pierced her arm as one stewardess bled to death, another lay comatose and an attacker blew himself up with his own grenade. Police captured the other terrorist, Fahad Mihyi, of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP), the man who had hatefully stared at Gerstel.

“The piece of shrapnel was removed from my arm and kept as evidence for [his] trial,” she recounts in her powerful one-hour documentary, “My Terrorist.”

The film explores the deeper psychic injuries Gerstel endured and how she overcame them by meeting Mihyi in 2000 and campaigning for his release from prison. The straightforward but intensely personal piece stands out amid the flurry of third-person documentaries emerging on the Middle East crisis, including Ilan Ziv’s 2002 suicide bombing expose, “Human Weapon,” and Oliver Stone’s “Persona Non Grata” (see page 26). Gerstel’s film has been controversial in Israel, where one columnist called the director a traitor.

In a phone in interview from Tel Aviv, Gerstel said, “Of course when I read these things I feel upset. But I have to raise my daughters in a war zone. And I want to show my little girls there is another way.”

Back in the late 1970s, however, Gerstel was overwhelmed by negative emotions. Around the time she testified in Mihyi’s trial, she said she “gained 20 kilos [44 pounds], my eyes were swollen … my heartbeat disordered. The diagnosis was hyperthyroid, [caused by] post traumatic stress disorder.”

While a daily pill stopped the physical symptoms, Gerstel continued to suffer from fear and survivor’s guilt. Every year, she scrupulously avoided the memorial service held for her slain El Al colleague.

Nevertheless, she began sympathizing with the Palestinian cause after the 1982 massacre at Sabra and Shatilla; by 1999, she was shooting a documentary about an exiled PFLP activist, Imad Sabi.

She said she was sitting in the Nablus living room of some Palestinian friends in 2000 when “suddenly I thought, ‘My terrorist could be sitting here in this room and I wouldn’t recognize him….’ After the Camp David agreement, I felt, ‘If Barak and Arafat can shake hands, everyone should find it within himself to meet his enemy. And Fahad Mihyi was my enemy.”

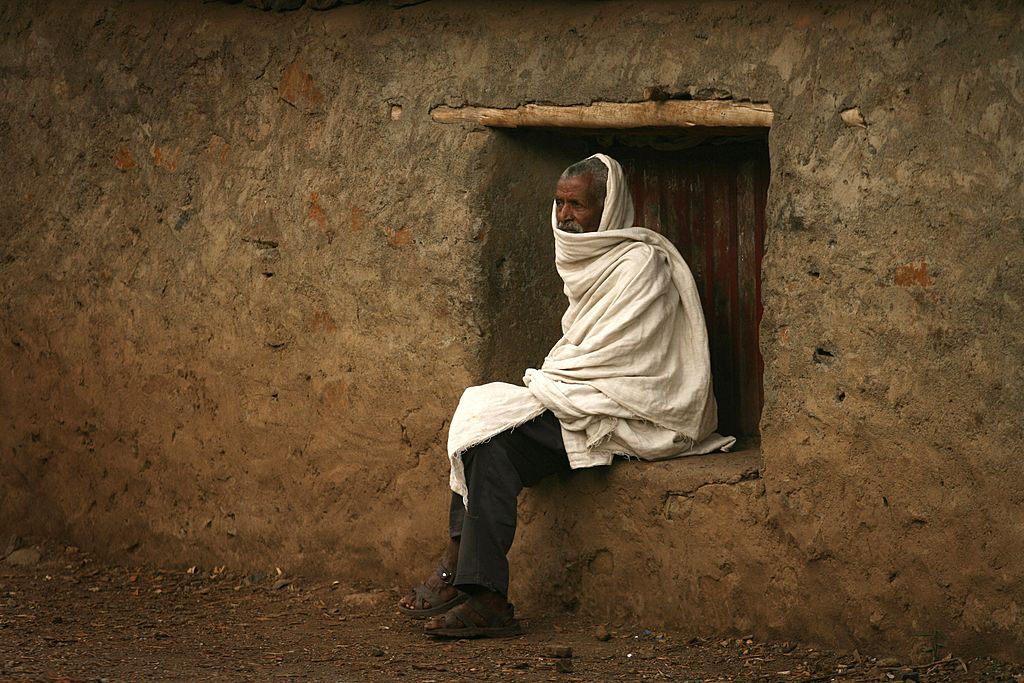

The filmmaker began tracking him down and, after locating him at Britain’s Dartmoor prison, she sat down to write him a letter in July 2000.

“Fahad, Salaam,” the letter began, “Are you aware of the Camp David agreement? I’ve been trying to figure out what happened to you personally and to Palestinians in general that turned us to be enemies.”

To her surprise, Mihyi responded with a deeply remorseful letter and in September 2000, Gerstel nervously waited to meet him at Dartmoor prison. The muscular, youthful-looking Arab who greeted her looked familiar, “except the hatred was gone from his eyes,” she said.

Over the next hour, Gerstel was mostly silent as he talked nonstop, profusely apologizing for his terrorist activities and touching on topics such as his childhood.

“The whole encounter was so emotionally loaded,” she said. “I looked at the window, trying to get oxygen.”

As she left the prison, however, she felt as if a weight had been lifted from her shoulders.

“I had felt so much fear and hate and guilt and trauma, that to meet the person who had created these emotions was to let go of them,” she said.

Gerstel agreed when Mihyi’s attorney asked her to write a letter to the parole board on his behalf. She learned that while he should have already been released from Dartmoor, he could not be deported, as required under British law, because he was stateless.

“So he was rotting in prison,” she said.

But Gerstel vacillated when the second intifada broke out two weeks later — and when terrorists attacked the World Trade Center in September 2001.

“I felt I could not go on helping Fahad, because everything was destroyed inside of me,” she said. “But then I realized that he believes in nonviolence, which is completely the opposite of the Sept. 11 attackers.”

Gerstel finally wrote to the parole board, and then gave up corresponding with Miyhi.

“His attorney told me that he was expected to be released, and that he wanted to disappear, to live a normal life, and I’ve respected that,” she said.

Assisting Mihyi has helped Gerstel return to a more normal life.

“Facing your worst fears is a difficult journey, but it’s worth it,” she said.

“My Terrorist” screens May 30, 8:30 p.m. at theDirectors Guild, 7920 Sunset Blvd., Los Angeles, as part of the AmnestyInternational Film Festival. For information, call (310) 815-0450. To purchasethe videotape, contact the U.S. distributor, Women Make Movies, at