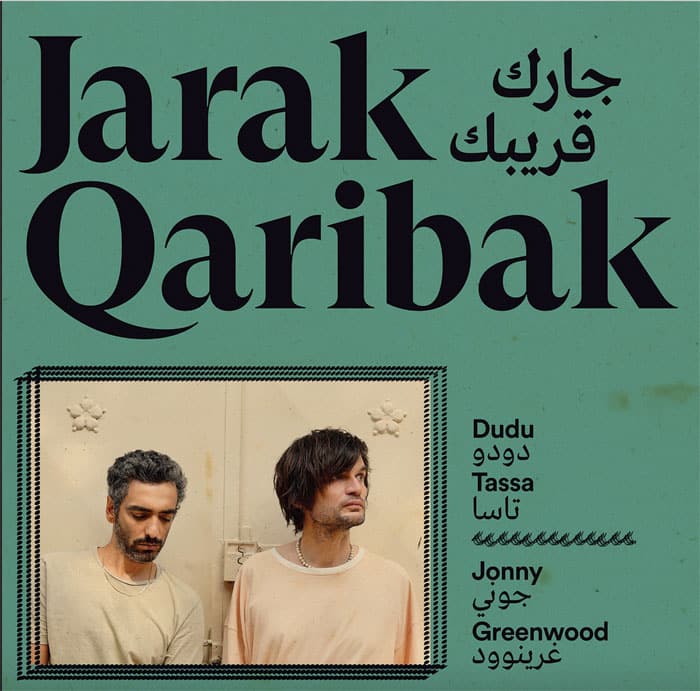

Dudu Tassa is quite emphatic that his new album, “Jarak Qaribak,” a collaboration with Radiohead guitarist Jonny Greenwood, is not a political album. But the Israeli Mizrahi Jewish musician, whose career has taken him from pop wunderkind to sought-after collaborator to a performer who breathes new life into classical Middle Eastern music, is savvy enough to know that the very existence of the album (the title’s loose translation, Tassa explains, is “Your Neighbor is Your Friend”) — which takes beloved songs from Israel, Morocco, Lebanon and Iraq, and matches them with singers not from the song’s country of origin, performed by a band that includes Muslims and Jews (plus Radiohead’s Jonny Greenwood) — carries with it political implications. Think of “Jarak Qaribak,” as a musical Abraham Accords.

To those who listen to Middle Eastern music, the rhythms and scales will sound familiar, but a closer listen reveals drum machines, synthesizers, loops, and other tools of modern recording.

It certainly sounds like nothing else out there. To those who listen to Middle Eastern music, the rhythms and scales will sound familiar — the music is distinctly Levantine — but a closer listen reveals drum machines, synthesizers, loops, and other tools of modern recording. Then there’s the liquid tone and unusual chord voicings of Greenwood’s guitar, which weaves through the songs like a guest at a party who’s visiting from out of town: Respectful but endlessly curious, figuring out the group dynamics, adapting to the unfamiliar idioms and accents. His guitar might come at the music from unexpected angles, but Greenwood finds a way to work within the song. There’s none of the preening, virtue signaling self-regard some pop musicians display when they attempt something outside Western music. It makes “Jarak Qaribak” one of those rare albums where a western rock star (for lack of a better term) collaborating with musicians in what is now called “Global Music” (also for lack of a better term) makes an album worth hearing.

Since he released his first album, 1990’s “Ohev et Ha’Shirim” (“Loving the Song”), when he was 13, Tassa’s made a dozen albums, including 2014’s “Ir u’Vehalot” (“City and Panic”) for which he was named composer of the year by The Society of Authors, Composers and Music Publishers in Israel (ACUM). In 2011, he formed a new band, Dudu Tassa and the Kuwaitis, and recorded an album of classic Iraqi Jewish songs written by his grandfather and great-uncle, Daoud and Salih Al-Kuwaity. The album was so successful (including Tassa being named producer of the year by ACUM) that he released two more albums with the Kuwaitis, 2015’s “Ala Shawati” and “El Hajar” in 2019.

His connection with Greenwood is a little more prosaic. After a show, the club’s owner came over and told Tassa his sister was married to Greenwood. “I thought, ‘yeah, right,’ and forgot about it,” Tassa told the Journal via Zoom (translated by his manager, Or Davidson); a few weeks later, he was face-to-face with the Radiohead guitarist. Greenwood was familiar with Middle Eastern music and had spent time in Israel with his wife, Israeli artist Sharona Katan. In 2009, they recorded their first collaboration, when Greenwood added a guitar part to Tassa’s “Eize Yom” (“What a Day”).

It sparked a musical connection. Radiohead started including Tassa’s music in their preshow playlists and, in 2017, Tassa and the Kuwaitis were invited to open for Radiohead’s U.S. Tour, which included two shows at Coachella. After a Radiohead show in Israel, the two musicians walked around Tel Aviv trying to come up with a project. Their initial thought was to record a soundtrack for a movie (both Tassa and Greenwood have written film scores), but decided instead to make an album of Arabic songs. “Jonny is very, very curious and is researching all the time,” Tassa explained, “this is what really connected with us both.”

Recording started at Greenwood’s studio in Oxford, England. After recording two tracks, Tassa returned to his home in Tel Aviv, and the two started working remotely, save for a few weeks when Greenwood and his wife were visiting her family in Tel Aviv. Tassa said their partnership worked because of the “things Jonny can bring to the music, the way that he thinks.” Greenwood had a way of approaching the music that was new to Tassa. “Jonny would bring up things I hadn’t thought of before,” he said.

Recording started at Greenwood’s studio in Oxford, England. After recording two tracks, Tassa returned to his home in Tel Aviv, and the two started working remotely, save for a few weeks when Greenwood and his wife were visiting her family in Tel Aviv. Tassa said their partnership worked because of the “things Jonny can bring to the music, the way that he thinks.” Greenwood had a way of approaching the music that was new to Tassa. “Jonny would bring up things I hadn’t thought of before,” he said.

Which isn’t to say there wasn’t a learning curve on Greenwood’s part. In traditional Arabic music, Tassa said “there is no harmony, there are no chords. [Greenwood] took the songs and the music and put in that harmony and those chords.” In press materials, Greenwood said he wanted to make music that sounded like “what Kraftwerk would have done if they had been in Cairo in the 1970s.” The band mixes traditional Middle Eastern instruments such as the oud, the rebab and qanun with synthesizers, brass, strings and guitar, bass and drums. The bass and the drums, Tassa said “give the music more life” and could help i reach a wider audience.

While Tassa insists “Jarak Qaribak” has no political import, the politics of the Middle East did intrude on the sessions. He admits his Mizrahi background made it easier for him to convince Arab singers to take part in the album, and only two performers declined his invitation. They didn’t say no because they didn’t like the project, he said, but because for some of them, “it’s really dangerous. They have families and they live in countries that wouldn’t accept the fact” that they recorded with an Israeli. When getting a visa for Iraqi singer Karrar Alsaedi became mired in red tape, he was smuggled into the country. “He was the only Iraqi passport holder in Israel at that time,” Tassa said, not without a little pride. Finding a studio in Beirut to record Lebanese singer Rashid al Najjar was also a problem; eventually a makeshift studio was set up in an apartment, but recording had to be stopped multiple times because gunshots on the street were picked up by the mic.

Tassa is optimistic the “music and the cultural collaborations we’re trying to do can help a little bit to bring people together in the Middle East.” It’s important to understand, he added, that Israel is a “really young country,” so a lot of the conflict is connected to that. It’s only been 75 years, but he “believes and hopes that, in the future, it’ll be better and we can live together with the Palestinians, the Israelis, everyone here.”

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.