Children posing for a photo in hats that read “Exodus 1947” in a displaced persons camp in Germany, September 1947. Photo by Robert Gary

Children posing for a photo in hats that read “Exodus 1947” in a displaced persons camp in Germany, September 1947. Photo by Robert Gary In the summer of 1947, when the British turned away the SS Exodus from the shores of Palestine, the world was watching.

Before the eyes of the international media, British troops violently forced the ship’s passengers — most of them Holocaust survivors — onto ships back to Europe. The resulting reports helped turn public opinion in favor of the Zionist movement and against the pro-Arab British policy of limiting Jewish immigration to Palestine.

But much else was happening in the aftermath of World War II, and attention soon shifted elsewhere. One of the few journalists to stick with the story was Jewish Telegraphic Agency correspondent Robert Gary, who filed a series of reports from displaced persons camps in Germany.

Seventy years later and decades after his death, Gary is again drawing attention to the “Exodus Jews,” albeit mostly in Israel.

An album of 230 of his photos will be sold at the Kedem Auction House in Jerusalem on Oct. 31, and a number of the images reveal the reality inside the camps, where the Jews continued to prepare for life in Palestine under trying conditions.

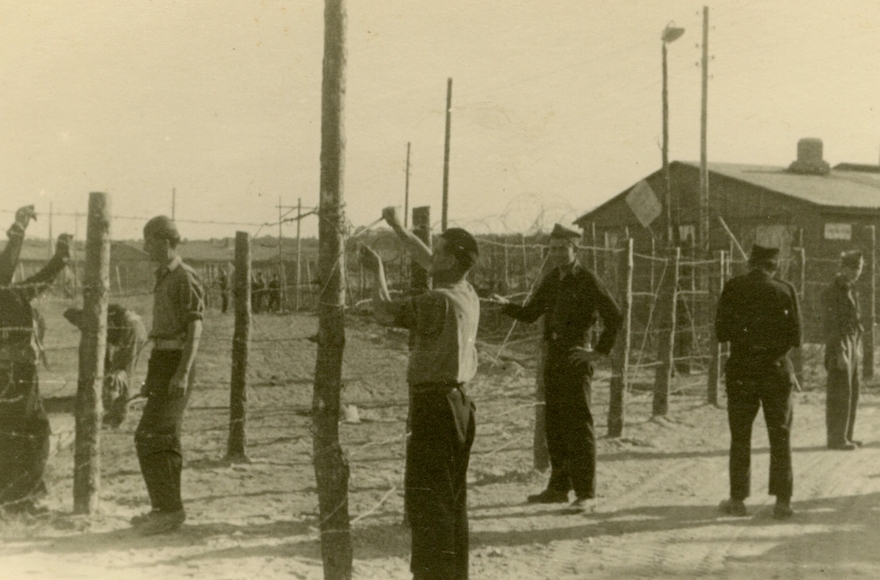

Some of the photos, which have little to no captioning, capture the haunting similarities of the DP camps to those in which the Nazis interned and killed millions of Jews during the Holocaust, including images of Exodus Jews repairing barbed-wire fences under the watch of guards.

But others show the Jews participating in communal activities and preparing for their hoped-for future in Palestine. In one photo, Zionist emissaries from the territory — young women dressed in white T-shirts and shorts — appear to lead the Exodus Jews in a circular folk dance.

Shay Mendelovich, a researcher at Kedem, said he expects there to be a lot of interest in the album, which is being sold by an anoymous collector who bought it from the Gary family. Mendelovich predicted it could be sold for as much as $10,000.

“The photos are pretty unique,” he said. “There were other people in these camps. But Robert Gary was one of the few who had a camera and knew how to take pictures.”

Jews dancing in a DP camp in Germany, September 1947. (Robert Gary)

Between 1945 and 1952, more than 250,000 Jews lived in displaced persons camps and urban centers in Germany, Austria and Italy that were overseen by Allied authorities and the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration. Despite having been liberated from the Nazi camps, they continued to languish in Europe under guard and behind barbed wire.

Gary was an American Jewish reporter who JTA sent to Europe to cover the aftermath of World War II. He detailed the living conditions in the camps more than a year before the Exodus journey: inadequate food; cold, crowded rooms; violence by guards and mind-numbing boredom. But he reported in September 1946 that the greatest concern among Jews was escaping Europe, preferably for Palestine.

“Certainly the DP’s are sensitive to the material things and sound off when things go bad (which is as it should be), but above all this is their natural desire to start a new life elsewhere for the bulk in Palestine, for others, in the U.S. and other lands,” he wrote. “Get any group of DP’s together and they’ll keep you busy with the number one question: When are we leaving?”

In July 1947, more than 4,500 Jews from the camps boarded the Exodus in France and set sail for Palestine without legal immigration certificates. They hoped to join the hundreds of thousands of Jews building a pro-Jewish state.

Organized by the Haganah, a Zionist paramilitary force in Palestine, the mission was the largest of dozens of mostly failed attempts at illegal Jewish immigration during the decades of British administration of the territory following World War I. The British largely sought to limit the arrival of Jews to Palestine out of deference to the often violent opposition of its Arab majority.

The Haganah had outfitted and manned the Exodus in hopes of outmaneuvering the British Navy and unloading the passengers on the beach. But near the end of its weeklong voyage, the British intercepted the ship off the shore of Palestine and brought it into the Haifa port. Troops removed resisting passengers there, injuring dozens and killing three, and loaded them on three ships back to Europe.

Even after two months on the Exodus, the passengers resisted setting foot back on the continent. When the British finally forced them ashore in September 1947 and into two displaced persons camps in occupied northern Germany — Poppendorf and Am Stau — many sang the Zionist anthem “Hatikvah” in protest. An unexploded time bomb, apparently designed to go off after the passengers were ashore, was later found on one of the ships.

Jews repairing fencing at a DP camp in Germany, September 1947. (Robert Gary)

Later, the Exodus achieved legendary status, most famously as the inspiration and namesake of the 1958 best-seller by Leon Uris and the 1960 film starring Paul Newman. Some, including former Israeli Foreign Minister Abba Eban, credited the Exodus with a major role in the foundation of the State of Israel in May 1948.

Gary, who was stationed in Munich, had close ties to Zionist activists; he reported early and often on the continuing plight of the Exodus Jews in the camps. His dispatches highlighted their continued challenges, including malnutrition, and unabated longing to immigrate to Palestine.

In a report from Poppendorf days after the Exodus Jews arrived, Gary said the dark running joke in the camp was that the alternative to Palestine was simple: “Everyone would choose a tree from which to hang himself.”

“The Jews of Germany demand and expect a chance to start life anew under reasonably secure circumstances,” he wrote. “They feel these places exist mainly in Palestine and the U.S. And they are determined to get there, either by legal or illegal means, or just by plain old fashioned patience.”

Pnina Drori, who later became Gary’s wife, was among the emissaries that the Jewish Agency for Israel sent to the camps from Palestine to prepare the Jews for aliyah. As a kindergarten teacher, she taught the children Hebrew and Zionist songs. Other emissaries, she said, offered military training in preparation for the escalating battles with the Arab majority in Palestine.

“In the photos, you see a lot of young people in shorts and kind of Israeli clothes,” she said. “We were getting them ready for Israeli life, both good and bad. You have to remember Israel was at war at the time.”

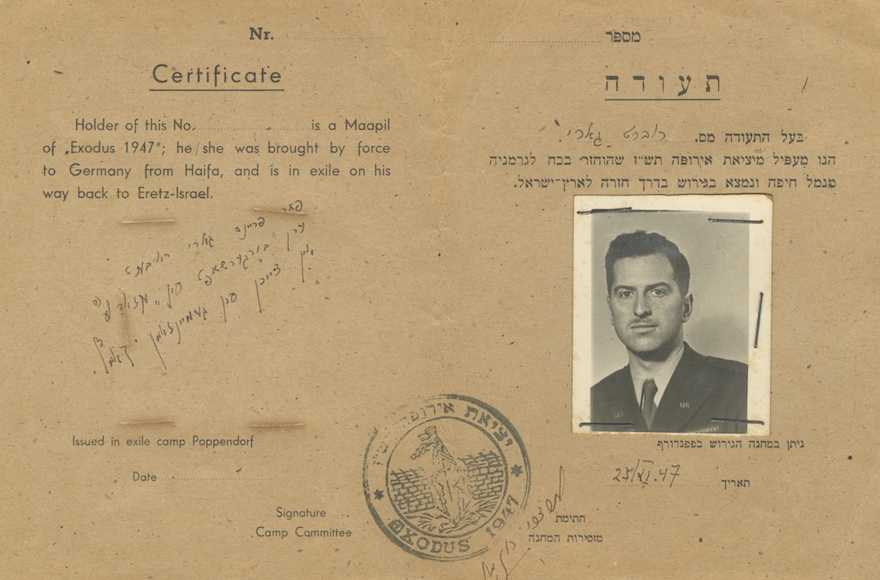

A 1947 photo of the fake certificate identifying Robert Gary as a passenger of the SS Exodus. (Courtesy of Kedem Auction House)

Gary was one of the few journalists who continued visiting the DP camps in the weeks after the Exodus Jews returned to Europe. Somehow he even obtained a fake certificate identifying him as one of the former passengers of the ship. But by late September 1947, JTA reported that British authorities had tired of Gary’s critical coverage and barred him from entry.

“The fact that Gary and [New York newspaper PM reporter Maurice] Pearlman were the only correspondents still assigned to the story, and had remained at the camps, aroused the authorities, who charged that they ‘were snooping about too much,’” according to the report.

Israel declared independence in May 1948, and after Great Britain recognized the Jewish state in January 1949, it finally sent most of the remaining Exodus passengers to the new Jewish state. Nearly all the DP camps in Europe were closed by 1952 and the Jews dispersed around the world, most to Israel and the United States.

Gary soon immigrated to Israel, too. He married Drori in 1949, months after meeting her at a Hanukkah party at the Jewish Agency’s headquarters in Munich, and the couple moved to Jerusalem, where they had two daughters. Robert Gary took at job at The Jerusalem Post and later worked for the British news agency Reuters. Pnina Gary, 90, continued her acting career.

She said her husband always carried a camera with him when he was reporting, and their home was filled with photo albums.

Decades after Robert Gary died in Tel Aviv in 1987, at the age of 67, Pnina Gary wrote and starred in a hit play, “An Israeli Love Story.” It is based on her real-life romance with the first man she was supposed to marry, who was killed by local Arabs in an ambush on their kibbutz.

“We knew life wouldn’t be easy in Israel,” she said. “That’s not why anyone comes here.”

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.