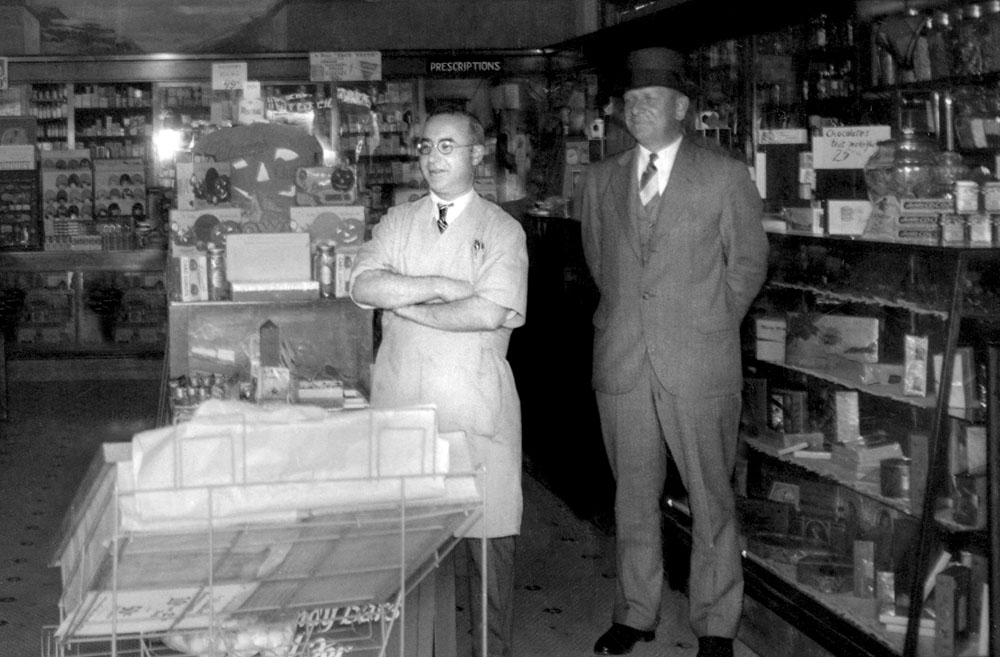

Photo courtesy of Simmons Family Archives

Photo courtesy of Simmons Family Archives In the years before Obamacare, health insurance and even penicillin, there was a health care provider of a more personal and community-based kind — the corner mom-and-pop drugstore where you could buy a cure for whatever ailed you.

Feeling nervous and dyspeptic? Buy a roll of Carter’s Little Nerve Pills. Feet hurt? Try the bunion plasters. Irregularity? Then a tin of Cocomint Laxatives might make you right as rain. And if you needed a prescription filled and someone to confide in about aches and pains, then you could go to Colonial Drug in Highland Park, an establishment owned by pharmacist George A. Simmons, a Jewish immigrant from Latvia.

In the 1920s, Simmons’ drugstore, a converted bank building at the corner of Pasadena Avenue (now North Figueroa) and Avenue 57, was a place of spotless black-and-white tiled floors, wood-and-glass display cabinets packed with bottles, boxes and tins of patent medicines, many of which contained alcohol and some even cocaine. Along one side was a long marble counter where you could be served an ice cream soda.

Although Colonial Drug closed in 1942 (Simmons opened a new store on West Adams Boulevard), it has re-emerged through the persistence of the Simmons family and a unique arrangement with a local museum. The drugstore now is located in the Heritage Square Museum, a collection of mostly late-19th-century structures north of downtown, just off the 110 Freeway. A visitor can examine the same ointments, tonics, salts and powders that Simmons was buying and selling, along with a collection of more than 80,000 pharmaceutical-related items that Simmons acquired throughout his career.

As mom-and-pop drugstores closed because of the Great Depression and the introduction of chain drugstores such as Thrifty Cut Rate, which was started by Jewish brothers Harry and Robert Borun and their brother-in-law Norman Levin in 1929, Simmons needed to find a way to stay in business. He discovered that he could bid at auction on the store’s contents.

“He could buy distressed merchandise for less than from a supplier,” said Dorothy “Dotty” Simmons, George’s daughter-in-law. With the auctioned merchandise, he could maintain his margins, even in the face of cut-rate competition. “It helped him to stay in business,” she said.

The only problem was, when he bid, he had to buy everything, including old patent medicines that were no longer moving off the shelves.

“He would box them up and put them in the basement,” she said. “When I entered the family in 1946, I went to this large house in Highland Park. The basement was this huge area. We used to call it the catacombs. It absolutely blew my mind. Cartons on top of cartons, floor to ceiling. He never threw anything away.”

In addition to Simmons, other Jewish families either worked in or owned Los Angeles-area pharmacies, including the Schwab brothers, known for their Sunset Boulevard location, and the parents of Rosalind Wiener Wyman, the youngest person ever elected to the Los Angeles City Council. Although not intended as a display of Jewish life, Simmons’ Colonial Drug stands as a kind of museum of the life of mom-and-pop enterprise that many Jewish immigrants lived upon coming to L.A. in the 1910s and ’20s.

“Family life revolved around the drugstore,” said Simmons’ granddaughter, Barbara Lazar. “All [four of] the sons worked there. Grandpa believed in starting by sweeping the floor and working your way up.”

From the shtetl of Preili in eastern Latvia in 1895, Simmons, born Avrom Gregorovich Simmonovitch, had worked his way up, too. His father was Chasidic, the family was Yiddish-speaking, and George attended yeshiva through age 14.

He left Preili at 14 for Vladivostok on the Trans-Siberian Railway to apprentice to a feldsher, an unlicensed medical practitioner. Moving to Shanghai, Simmons worked for J. Llewellyn & Co., where his first job was to sell packets of opium, used for pain relief, to the local Chinese population.

By around 1909, he had become the company’s senior pharmacist. While in Shanghai, he also met his future wife, Renee Begelman. With the Russian draft reaching into China for conscripts in 1916, “he left Shanghai on the first available ship,” Dotty said.

Landing in Vancouver, British Columbia, Simmons crossed the border into the United States illegally and settled in Seattle in 1917, when he began working at various day jobs. Also that year, he enlisted in the U.S. Army, where he was assigned to the medical corps. In 1918, he was honorably discharged, and as a result of his service, earned his U.S. citizenship. Renee joined him in the U.S., and the two were married. As newlyweds, they moved to Los Angeles, where Renee’s brother was living.

The 1920 census shows the family living on Cummings Street in Boyle Heights and George listing his occupation as “pharmacist” at a drug company.

“He never went to pharmacy school,” Dotty said. Nevertheless, through self-study and his training and experience he passed the licensing test and, in the early 1920s, opened Colonial Drug in Highland Park.

By 1930, the Simmons family was living on Gage Street in the East L.A. community of Belvedere, a neighborhood with Russian Jews, according to the census. Around the early ’30s, the family moved to Highland Park. There, George filled the basement and the garage with his bargains, then built another garage.

At the various locations of his pharmacy over the years, a group of customers the family referred to as “pigeons,” because they flocked to George, sought him out for his supply of over-the-counter remedies that were unavailable elsewhere and for his pharmaceutical knowledge.

George died in 1974, leaving behind the contents of the catacombs.

The collection stayed in storage in the San Fernando Valley. The 1994 Northridge earthquake destroyed about a third of the collection, prompting George’s son Sidney, also a pharmacist, to inventory and photograph the remaining items.

As that work progressed, another of George’s sons, Fred, an attorney, approached the Heritage Square Museum with a proposal to take the collection and house it in a re-creation of Colonial Drug Store that the family would build and donate in George’s honor. The museum agreed to take the collection but balked on the building.

“It was inconsistent with the museum’s normal mission,” said Philip Simmons, Sidney and Dotty’s son, a real estate attorney and development manager, who managed the construction of the building.

By 2008, the museum came around, and a design was agreed upon: The building housing the period medicines and pharmaceuticals would be a reproduction of the original structure. As the building was under construction, the family pitched in to sort through and curate the collection, pulling out such gems as Karnak Stomach Tonic, Kuke’s Dandruff Exterminator and Ingram’s Complexion Tablets.

In 2012, the Colonial Drug exhibit opened. Today, almost 100 years since the store’s opening, the family is still in the pharmacy business, with Valley Drug and Compounding in Encino.

George supported much of his extended family with his drugstore, Dotty said.

Even with his vast collection, George never undervalued the healing power of the patient. Said Philip: “He believed that the individual’s belief in the treatment was as much a part of its effectiveness as the treatment itself.”

Have an idea for a Los Angeles Jewish history story? Contact Edmon J. Rodman at edmojace@gmail.com.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.