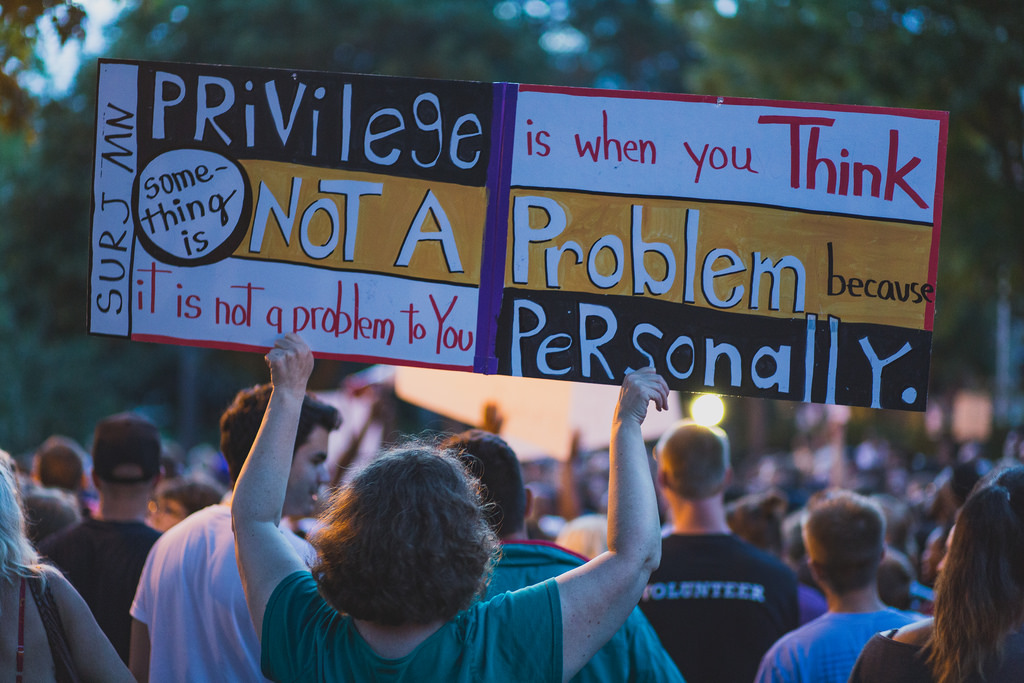

Photo from Flickr/Tony Webster.

Photo from Flickr/Tony Webster. I sometimes joke that if there’s anything I’ve learned in three years at UCLA, it’s how to spell “privilege” without spell-check.

In the age of identity politics, the concept of group-based privilege frames nearly every political discussion on college campuses, from debates on immigration to the Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions movement.

The idea is that nearly all of us benefit from some combination of unearned, identity-based advantages embedded in American socio-historical structures. People must “check their privilege,” or adjust their everyday behavior accordingly, by trying to dismantle the structures that give their identity groups a leg up.

This shift in political language poses crucial questions for Jewish students: Do Jews have privilege in America, despite persistent anti-Semitism? If so, what are we doing with that privilege?

Our answers could determine whether we are included within progressive campus circles, which generally regard checking one’s privilege as a signal of solidarity with other marginalized students.

The question of whether Jews have white privilege surfaced in June, when light-skinned Israeli actress Gal Gadot starred in the film “Wonder Woman,” and again in early August when white supremacists chanted anti-Semitic slurs at a far-right rally in Charlottesville, Va.

In his Jewish Journal column about Gadot’s casting, Shmuel Rosner asked, in perhaps one of the most pronounced examples of the generational gap in Jewish priorities, “Who cares if Gadot is white?”

The answer to that question is, of course, college students — including the Jewish ones who reject the very pretense of the progressive expectation that we recognize our privilege. These students claim it’s an insult to say Jews benefit from white privilege in this country when anti-Semitism has often relegated us to otherness.

In 2014, Tal Fortgang, a Jewish freshman at Princeton, appeared on Fox News regarding an article he wrote, “Checking My Privilege,” in his campus conservative magazine. Fortgang argued that accusations of white privilege erased the reality of anti-Semitic oppression his Jewish ancestors faced in Nazi Germany.

“Perhaps it was the privilege my great-grandmother and those five great-aunts and uncles I never knew had of being shot into an open grave outside their hometown,” Fortgang wrote. “Maybe that’s my privilege.”

Other Jewish students feel the burden of Jewish privilege on their shoulders — even more so when it goes unrecognized by the larger community. Prior to this year’s AIPAC Policy Conference, UCLA student leader Rafael Sands penned an op-ed to the Jewish Journal called, “Why I’m Skipping AIPAC This Year.”

Sands explained the moral conflict he felt as an American Jew: Yes, Jews face anti-Semitism, sometimes subtly and other times hideously, but Jews also have come a long way — succeeding at getting our foot in the door of American politics (AIPAC’s magnitude a case in point) and, by extension, American privilege.

We must consider the need to reckon with the Jewish place in the narrative of American white privilege.

Inviting Donald Trump and Mike Pence to speak at AIPAC represented American Jewish complicity in the administration’s ban on Muslim immigration, animosity toward undocumented people and hostility to reproductive choice, Sands wrote.

I hope my non-Jewish peers agree that it was refreshing to hear such remarks from a Jewish UCLA leader. The work of justice requires, before anything else, that we address our flaws.

This is not to say there isn’t a serious need for progressives to grant more legitimacy to claims of anti-Semitism, which sometimes seem to get thrust outside the circle of real oppressions. We should never have to choose between condemning anti-Semitism and supporting social justice movements.

In our own community, though, we must consider the need to reckon with the Jewish place in the narrative of American white privilege, the reality that some Jewish people and institutions have been reluctant to do so, and a progressive alliance that’s not going to wait for us while we figure all of this out.

If Jewish students want to be true partners to our progressive peers, it is our responsibility to check our privilege — even if, at times, we’re unsure what we will find.

Gabriella Kamran is a third-year communications and gender studies student at UCLA.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.