wynnter/Getty Images

wynnter/Getty Images After nearly two years of the pandemic, doctors like me need a break. Relief arrived in the form of an invitation to visit friends in Washington, D.C. We started the trip with four days in central Virginia. As a long-time Civil War buff, I looked forward to visiting the area’s historic battle sites. Along the way I discovered some lessons about democracy that echo across those hallowed fields.

Much of the war’s bloodshed occurred in the 100 miles between D.C. and Richmond, the Confederate capital. The blue and gray armies faced off in a seemingly interminable series of battles with the Union angling to capture Richmond, only to be repeatedly repulsed by Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia.

On our way to Washington, my wife and daughter indulged me in a visit to Manassas, near Bull Run Creek, site of the war’s first battle in July of 1861. There on Henry Hill, now home to the Visitor Center, the amateurish forces from North and South, scarcely true armies, faced off against each other with the southern confederates ultimately driving the Union soldiers back to Washington. Suddenly, the nation awakened to realize that the South would not simply fold in the face of Union power. This would be a real war. Yet, no one yet imagined the bloodbaths to follow.

If we only pay attention, the torrent of blood soaked into Virginia’s soil still cries out to us.

Thirteen months later the armies engaged again near Manassas. My family and I were the only attendees at the afternoon Ranger talk at Brawner’s farm, site of the first day’s combat at the second battle at Bull Run. By then, both side’s forces had evolved into highly professional, deadly armies. The Ranger eerily described the night-time clash. A soldier was killed or wounded on that spot every 10 seconds for two hours. I asked how that compared to the Antietam cornfield, a site I’d visited years ago and a battle that occurred only months later. “At the cornfield,” he responded, “a soldier was killed or wounded every second for four hours.” The mind reels at individual tragedies and destroyed families generated at an industrial rate. Antietam was the bloodiest day in American history, with nearly 23,000 killed or wounded.

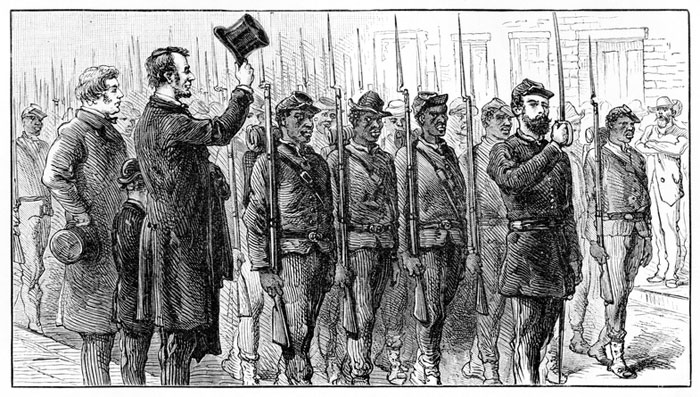

Why would soldiers throw themselves willfully into the very face of death? One might hope that Northerners thought that ending the evil of slavery justified the ultimate sacrifice. Yet Lincoln had not yet issued the Emancipation Proclamation. He had campaigned to limit slavery to existing territory, not to abolish it. As Lincoln later commented, the conflict tested whether government “of the people, by the people and for the people” could endure.

Contemporary Americans may forget the audacity of the American experiment inaugurated less than a century earlier. Democratic republics were widely viewed with skepticism and their future far from secure. Many American families remembered persecution by old world governments whose authority sprang from brute power or purported divine right. The American system, with its legitimacy drawn from consent of the governed, a peaceful and systematic succession of power and constitutionally limited powers, translated into a safe and secure future for themselves and posterity. The nobility of that experiment and its hope for the future of mankind justified such profound sacrifices.

What would a soldier at either Bull Run battle, or Antietam, think about an appeal from the President of the United States to a Georgia official to “find” the 11,780 ballots needed to win an election? What might Lincoln say about a Vice President, charged with counting electoral votes, pressured to unilaterally overturn the votes—and the will—of millions of voters?

January 6, 2021 marked our first failure to peacefully transfer power since the South’s secession. Those failing to understand the gravity of that loss and the recent threats to democracy owe themselves a visit to the now hushed battlefields of eastern Virginia. We should understand that the efforts to overturn our election desecrate a national heritage forged by the countless lives lost at Bull Run, Antietam and elsewhere. At Henry Hill and Brawner’s Farm, Lincoln’s words, spoken at Gettysburg, still ring true: It is “for us, the living, to be dedicated to the unfinished work, which they … so nobly advanced.” If we only pay attention, the torrent of blood soaked into Virginia’s soil still cries out to us.

Daniel Stone is Regional Medical Director of Cedars-Sinai Valley Network and a practicing internist and geriatrician with Cedars Sinai Medical Group. The views expressed in this column do not necessarily reflect those of Cedars-Sinai.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.