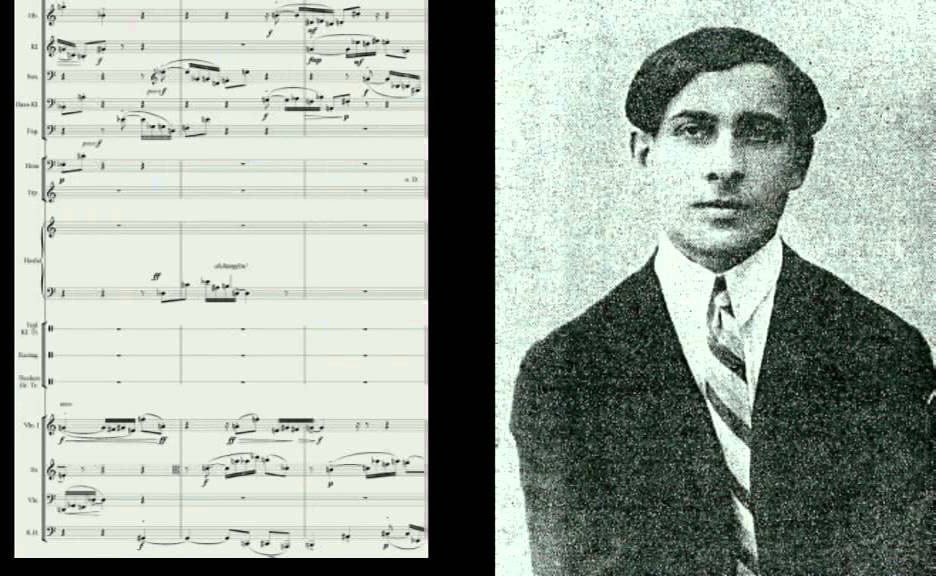

Philip Herschkowitz (YouTube screenshot)

Philip Herschkowitz (YouTube screenshot) On an ordinary Tuesday in 2017, a Facebook message from a stranger popped up on my phone.

“Dear Sara Hershkowitz, are you related to Philip Herschkowitz, composer, from Iasi Romania, who studied with Alban Berg?”

I texted back that I didn’t know but that I thought it possible.

“Because if you are, Philip Herschkowitz, who studied with Alban Berg in Vienna before the Nazi’s came, died with no heirs. He left his entire musical estate to the Vienna Public Library.

If you think there’s a chance you might be a descendant, or even if you’re not, they’d love for you to come look through the archives. Maybe consider performing some of it?”

I blinked at the screen. Alban Berg was the composer I had been most obsessed with since I was 21 and stumbled across Lulu in the Manhattan School of Music library.

My voice teacher at the conservatory had once said “You were born to sing Alban Berg’s Lulu” and I secretly agreed.

Berg’s music was dark, sensual, cinematic. Occasionally sinister, occasionally angelic.

And now maybe I was related to someone who knew him personally….? My heart leapt into my throat like a starstruck teen.

Was there a family tree that might connect us? Most likely any birth certificate of any other evidence of a common lineage would have been lost or burned in the war. It would be almost impossible to know for sure what connection—if any at all—I might have to Philip Herschkowitz.

It did not matter.

It did not matter because the possibility now existed that I had had an ancestor who had gone through the exquisite highs and lows of a life in music, the way I had.

And this tiny glimmer of possibility made me feel a bit less lonely in the world. I did not exist as an island. I was maybe part of a lineage.

And that is why I booked myself an economy class flight from Los Angeles to Vienna in January of 2018, to immerse myself in the archives and pore through the musical estate of the man who I now believe is my great-grandfathers nephew.

They say that in Vienna the ghosts are friendlier than the living.

I’d been to Vienna before but this time I could not shake the sense that all my past, future and present selves were all lined up inside me like those Russian Matryoshka dolls.

On a cold, rainy January day, I had my first appointment with Herr Aigner, the head librarian in charge of Philip’s estate.

I put on a camel wool coat, high-heeled boots and a man’s fedora hat. When I paused to look in the mirror before leaving the AirBnB, a fancy lady looks back. I thought my own face looked like a face from 1933.

When I arrived at the gothic library of the Vienna Bibliotek, Herr Aigner invited me into his office.

I sat across from him clutching my umbrella.

He started by saying how close Philip had been to Alban Berg. Berg had thought the world of Philip and his talent.

He mentioned that Philip had fled the Nazi’s and moved to Russia and how the Soviets then blacklisted him because he taught serialism, a post-tonal composition style, which the Russians considered to be subversive.

“Philip Herschkowitz was always on the wrong side of politics”, Aigner explains “ Or, maybe more accurately, the right side—for this his music was never given a fair chance.”

I did not have the chills at that moment, my DNA did not respond.

I just nodded.

It wasn’t until later that afternoon, in the library archive, when I was holding Philip’s ancient, yellowing scores in my gloved hands and look at the original faded pencil markings on the fragile paper, that something sparks inside me. It is as if a string of lights is suddenly switched on, illuminating a secret passageway that I am just now realizing has been there all along.

Herr Aigner warned me that I was not allowed to take any music out of the archive but I was allowed to take as many photos of the score as I liked.

So I clicked away, and managed to take about 80 pages worth of photos my little iphone 7. When I was done, Aigner stopped me.

“Wait. Take this” he said, handing me a scary looking, small-printed paperback book entitled “ Philip Herschkowitz.”

I took it but secretly winced, figuring it was a book on music theory.

I winced because there was no way I was going to read a thick book on serialist music theory, not even if I was related to the guy. And definitely not auf Deutsch.

But on the flight home I cracked open the cover. To my astonishment, it was not a book on music theory at all.

It was a book of Philip’s letters. His private letters to Alban Berg.

“Sehr geehrte Herr Berg”, read one. “ I only have 150 per month to live on. This means I would have to beg for free lessons from you…. all I truly need now is one lesson a month. But what I really need most, quite simply, is to be in your presence.”

“But not in your presence, as in, having a cigarette together, but your presence, meaning, in a sitting tempo, sitting at a table decorated with flowers, with you, I want to be useful to you, in whatever way works the best, I want– for example– to make corrections for you, to bring them to you in the bath.”

In my little cramped seat of 23D on the Easyjet flight home, I wept into the pages. Was this a love letter? Or merely a student devoted to his teacher?

I didn’t know but love is love is love and the point was: his letters to Alban Berg were filled with it.

The flight attendant came with coffee and I wiped my eyes with an airplane napkin. Then I kept turning the pages, until I saw a photograph of Philip as a young man. I could not stop staring at it. He looked about 25, with pale, smooth skin, midnight-black hair, parted on the side and eyes so liquid, so deep, so long-lashed it almost looked like he is wearing eye-liner. He has a strong nose and an oval face. He looked like a cartoon cliché of an artist. But there was something else he reminded me of and it took me a second to realize: He was the spitting image of my father and his brothers. He even looked….well, he looked a little bit like me.

I closed the book, opened up my phone to look at all the photographs of Philip’s sheet music. Some were with words in smeared smudgy ink. Some were song texts in Romanian, in curly old-fashioned handwriting.

When I put the phone down I understood that somehow I had been give a task.

*************

“I have to sing them,” I said into the cell phone, my voice brimming with excitement. “ I have to somehow bring them back into the world.”

I had only been home in Berlin for about three hours but had already called up the stranger from Facebook.

The stranger from Facebook, I’d since learned, was no ordinary stranger but a brilliant man called Michael Hass. Michael worked for Exilarte, an organization that takes care of the estates of composers who were persecuted by the Nazis.

“If you could somehow get in touch with the pianist Elisabeth Leonsakaja and collaborate with her, you’d easily get booked for a concert in Vienna. Elisabeth was Philip’s student in Moscow. I know she expressed interest awhile back in doing his music. Ask Herr Aigner.”

Elisabeth Leonskaja, the famous Russian pianist, had studied with Philip? And wanted to perform his music? But why hadn’t she done so already? I was excited to call her.

In retrospect, believing I could simply call up a legend like Elisabeth Leonskaja was as delusional as thinking I could simply “casually reach out” to Martha Argerich.

As if this was just any ordinary human who happened to play piano. Contacting Leonskaja would be quite a long shot with a lot of gatekeepers who would protect the airy, famous-person-perimeter around her.

But connecting with her was also the best shot I had at bringing back Philips music.

When I emailed Herr Aigner about it he was cagey.

Liebe Frau Hershkowitz, I cannot give you Frau Leonskaja’s email…. I am sorry but I have a duty to protect her privacy. If you want to try and reach her another way, fine. I am sorry I cannot help you further.

So I typed the words into a Google search on my laptop:

Elisabeth Leonskaja, Agentur, and a phone number popped up.

I picked up my cell phone. “Ja! Guten Tag. My name is Sara Hershkowitz. I’m calling to get in touch with Frau Leonskaja? I believe that I am that great-grand cousin of the man who was one of her most important teachers, Philip Herschkowitz—“

The agent interrupted me.

“Frau Leonskaja is a very busy woman who has many demands on her time and I would not advise you to get your hopes up. However I will give you her email.”

This is a long shot, I told myself. Don’t get your hopes up. But I was off to the races.

And because the rule in life always seems to be that when you expect nothing, things happen, the following email arrived:

Dear Sara Hershkowitz,

It is a phenomenal news- to know that somewhere in the world are the relatives of our (my, Alexei Lubimov (my great kollege ) and many other musicians in Moscow) teacher Phillip Herschkowitz.

P.S Call me Lisa.

And that was the beginning of everything.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.