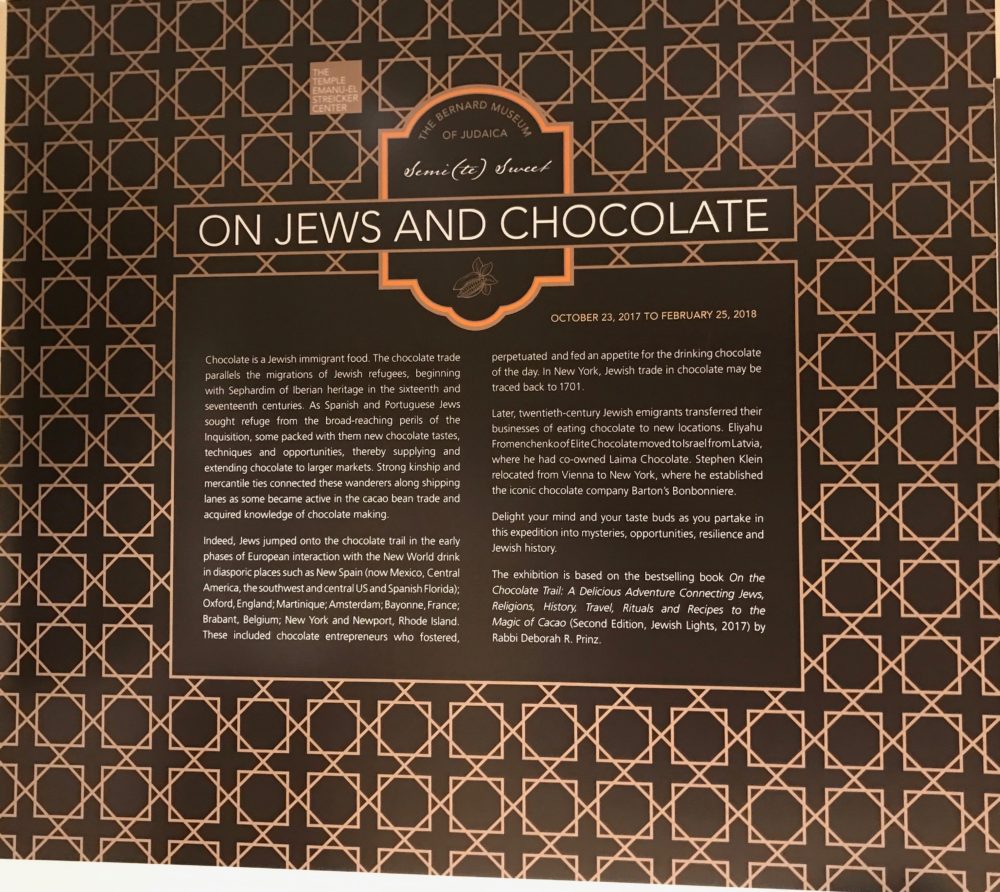

Jewish refugee and immigrant stories highlight chocolate as a migrant food in “Semi[te] Sweet: On Jews and Chocolate” currently on display at Temple Emanu-El’s Herbert and Eileen Bernard Museum of Judaica in New York City. Now in its 20th year, the mission of the Bernard Museum is to examine and engage with the intersections of Jewish history, culture, and identity.

The exhibit invites visitors to partake in this first-ever visual journey into the mysteries, opportunities, and resilience of the Jewish chocolate story. It focuses on the surprising chocolate businesses and skills of Jews that cross cultures, countries, and continents. Jews jumped onto the chocolate trail in the early phases of European interaction with the New World drink. Later, 20th-century Jewish emigrants transferred their businesses of eating chocolate to new locations.

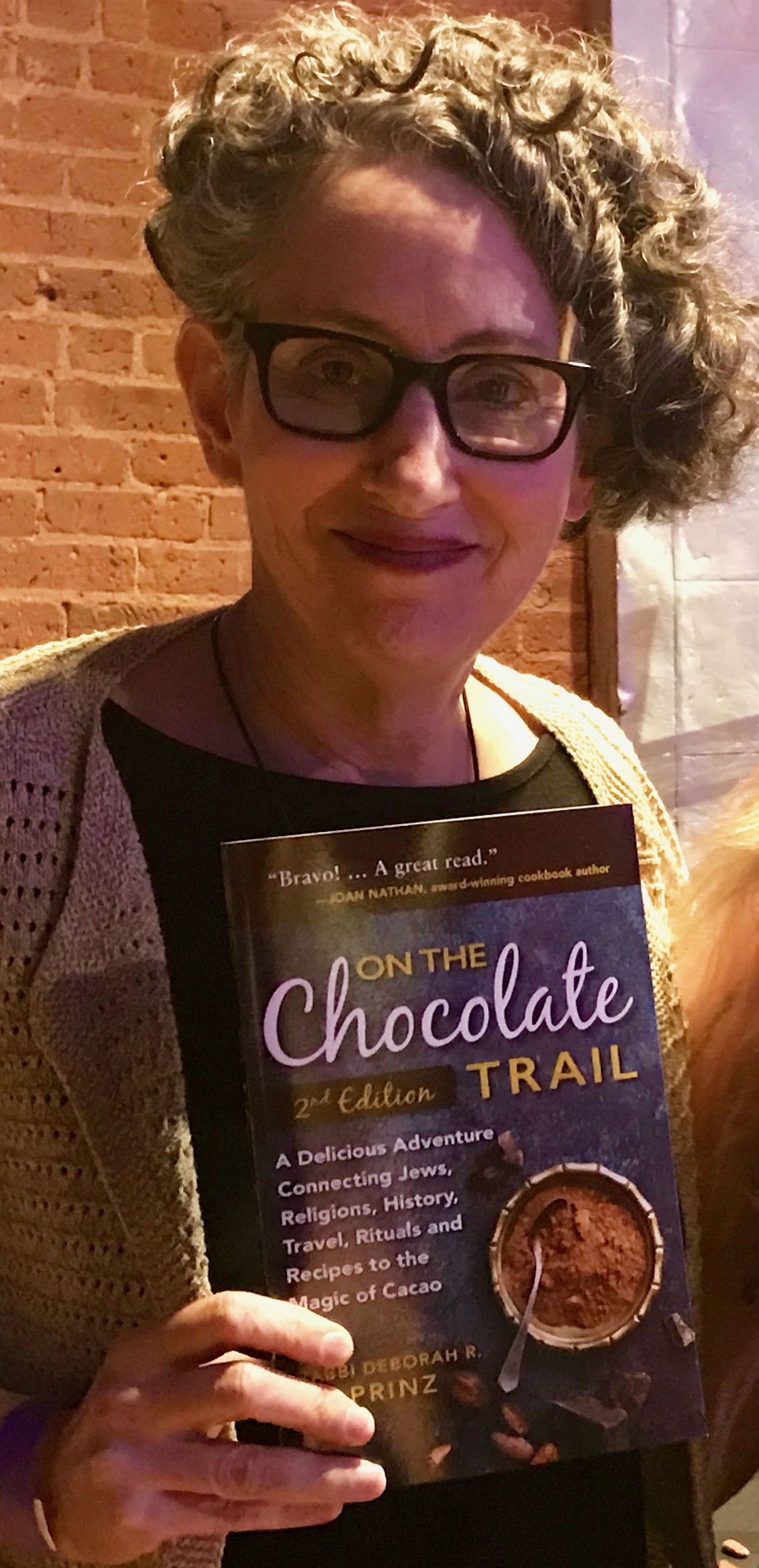

Some books are optioned into films. My book, On the Chocolate Trail, developed into this museum exhibit. Truthfully, creating this exhibit was the fulfillment of a dream. As I had researched chocolate and religions for On the Chocolate Trail, I had come across many charming artifacts, unusual pieces of decorative arts, and elegant archival documents. Understandably, only a handful could be included in the publication. All the while, I mused about the many items that amplify the narratives and potentially could comprise a delightful display about the little- known history of Jews and chocolate.

“Semi[te] Sweet” started with a serendipitous encounter in 2016 when I randomly sat next to an Israeli colleague at a Women’s Rabbinic Network dinner in Jerusalem. She happened to work at Museum of the Jewish People or Beit Hatefuzot. The rabbi took a copy of On the Chocolate Trail at the end of the evening. Almost a year later, when Gady Levy, the director of Temple Emanu-El’s Streicker Center in New York, NY, met with her in Jerusalem, she handed him On the Chocolate Trail. Within weeks, Levy and I met with Warren Klein, the Bernard’s curator, in New York, and a year later we mounted the show.

Of course, I had no idea about the complexities of such an enterprise: locating and borrowing the articles, designing the space, coordinating the labels. The expertise, professionalism, and creativity of Klein, who has been the museum’s curator since 2013, and his team were essential. We often juggled wishes with availability, vision with budget, aesthetics with content. Some manuscripts could only be provided in facsimile since the originals were deemed too fragile to travel.

Using On the Chocolate Trail as a foundation, we sought relevant objects. We reached out to institutions that had supported my research such as The Jacob Rader Marcus Center of the American Jewish Archives, the American Jewish Historical Society, the Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion Klau Library, and the Newport Historical Society.

When we decided to portray early chocolate usage, I turned to social media to locate pieces. As a result, eclectic loans included a family chocolate cup from Mexico lent by Reverend Susan Sica, whom I had met on an interfaith clergy trip to Israel. Michael Laiskonis, a chocolate expert at the Chocolate Lab at Institute of Culinary Education provided his metate stone for the grinding of chocolate by hand. A rabbinic colleague’s wife furnished a silver chocolate pot that had been in her family for three generations. The Leo Baeck Institute in New York City worked closely with Klein to bring Albert Einstein’s childhood chocolate cup back from loan in Germany. The Barton’s Bonbonniere founder’s son generously lent company memorabilia as did a member of the Barricini Family.

Although I could not imagine how it would all come together, Klein coordinated with a designer, a graphic artist, a painter, and an installer to be sure everything fit in a balanced confection of an installation. Its elegant and smart look entranced 800 attendees at the chocolate suffused opening and many more since. The evening happily coincided with the publication of the second edition of the book. On the Chocolate Trail then served as the catalog for the exhibit.

Guests from around the world – Argentina, Australia, Canada China, England, Israel, and Poland – have written sweet comments in the guest book. Tour groups have enjoyed specially themed Elite milk chocolate bars. Florence Fabricant in the New York Times noted that the exhibit demonstrates that “The connection between Jews and chocolate goes beyond Hanukkah gelt.” In response to inquiries from across the country, “Semi[te] Sweet” will be available to travel to museums and galleries beginning in April. After all, from generation to generation, l’dor vador, the Jewish love of chocolate should be shared.

“Semi[te] Sweet: On Jews and Chocolate” will be traveling around the country beginning in April, 2018. For further information, please contact me.

Cross posted from ReformJudaism.org.

Rabbi Deborah R. Prinz speaks about chocolate and Jews around the world. The newly released second edition of her book, On the Chocolate Trail: A Delicious Adventure Connecting Jews, Religions, History, Travel, Rituals and Recipes to the Magic of Cacao, (Jewish Lights) contains 25 historical and contemporary recipes. She is co-curator of the exhibit, “Semi[te] Sweet: On Jews and Chocolate” at Temple Emanu-El’s Herbert and Eileen Bernard Museum of Judaica, NYC, on display through February 25, 2018. She blogs at the Forward, onthechocolatetrail.org, and elsewhere. The book is used in adult study, classroom settings, book clubs and chocolate tastings.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.