Coronavirus vaccine. A vaccine against COVID-19 Coronavirus in ampoules on aged wooden table

Coronavirus vaccine. A vaccine against COVID-19 Coronavirus in ampoules on aged wooden table The coronavirus pandemic has given rise to some of the most complex and significant medical-ethics dilemmas in recent history, namely the question of triaging ICU care and, by extension, who shall live and who shall die.

This was a question previously thought to be only the stuff of theoretical classroom debates. As society begins to contemplate how to readjust to the new normal, and eventually lift isolation, new and similarly challenging ethical questions will arise.

One being debated now has not yet received much discussion, but I believe requires our community’s attention. It revolves around the rush to develop a vaccine. While it could take well over a year before any vaccine is available, the ethical issues likely will be here much sooner.

While it could take well over a year before any vaccine is available, the ethical issues will likely be here much sooner.

One reason developing a vaccine takes so long is that researchers have to randomize test subjects into two groups. Group A gets the vaccine; group B gets a placebo. Researchers wait and see if more people from group B get sick than those in group A. If that happens, it is a sign that the vaccine is effective. However, it can take many months before researchers get their answer because, in its simplest form, this kind of study depends on waiting for people to be naturally exposed to the virus, which takes even longer amid social distancing.

To speed up things, an alternative is to do something called a “challenge study.” In a challenge study — just like the traditional study above in which some people are given an experimental vaccine and some are not — everyone in the study is deliberately exposed to the coronavirus. Researchers then compare the two groups: the vaccine versus the control. Running a study in this manner could save several months (and thousands, if not millions of lives). However, to expose people to the coronavirus makes this a much riskier study. Some may get very sick and a few may die.

When it comes to engaging in risk in general, Judaism obligates us to attempt to help those in need, such as jumping into a river to save someone who is drowning.

How does Jewish law and values guide us in this? When it comes to engaging in risk in general, Judaism obligates us to attempt to help those in need, such as jumping into a river to save someone who is drowning. But the degree of risk one is required (or permitted) to take to save life is a matter of debate. The general consensus is that although one is not obligated to put his or her life at risk to save another person, it is praiseworthy to do so — unless there is a significant risk; in which case, doing so may be forbidden. The rabbis encourage us to make a cost-benefit analysis of the level of risk versus the amount of good that can result.

For example, kidney donation, which carries some risk, is encouraged but not required, whereas bone-marrow donation, which carries negligible risk, may be viewed as obligatory when performed to save a life. For that reason, I believe once plasma donations from those who have recovered from the coronavirus is shown to be safe and effective in treating current coronavirus patients, it can be seen as an expectation of Jewish law that those who have recovered must make such blood donations if they are able to.

The benefit of attempting to save the entire society (known as “hatzalat harabim” or “saving the many”) is given even more weight in Jewish law. For example, Queen Esther risked her life by approaching Achashverosh since it was to save the entire community. Similarly, the Talmud relates that in the city of Lod, the Roman emperor’s daughter was murdered and the Jewish community was blamed. The emperor threatened the Jews with mass execution unless they could produce the murderer. To save the Jewish people, two innocent brothers, Lilianus and Pappus, stepped forward and falsely confessed to the crime. Only they were executed by the Romans, sparing the rest of the Jewish community. Many rabbinic authorities permitted voluntary self-sacrifice to rescue the broader community, based on Esther and the Talmudic praise for these righteous brothers.

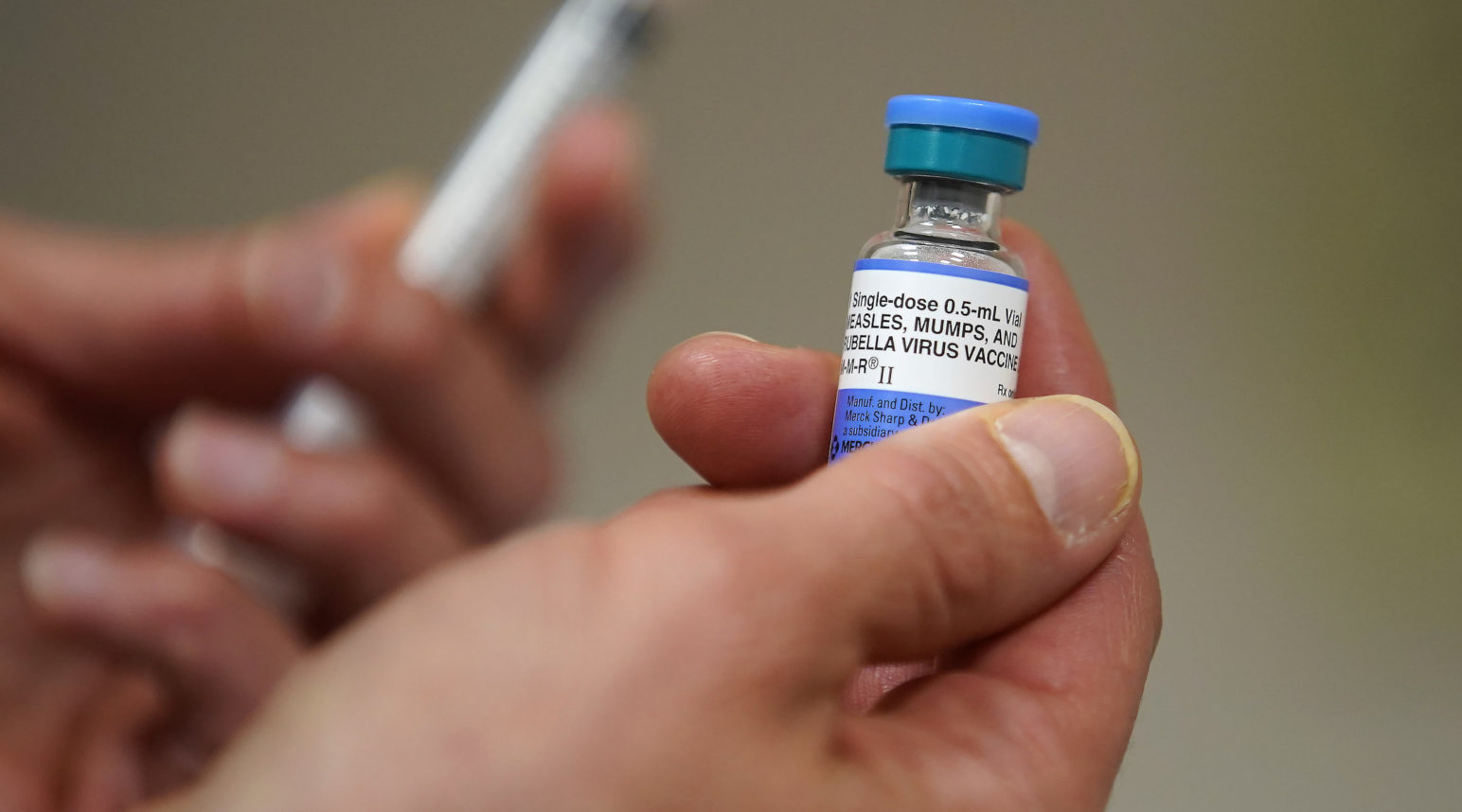

A one-dose bottle of the measles, mumps and rubella virus vaccine. (George Frey/Getty Images via JTA)On the other hand, other rabbinic authorities argued that although saving the community is a very high value, and one should engage in small risk to attempt to do so, these stories do not prove that one who is not currently in any danger may opt to risk his or her life for the sake of the community, since the brothers in Lod and Esther would have died along with their community anyway.

It would certainly be permitted for a Jew to serve as a participant in a challenge study associated with rapidly developing a vaccine for the coronavirus, and even a very pious act.

This brings us back to the “challenge study.” I believe the lesson here is that it certainly would be permitted for a Jew to serve as a participant in a challenge study associated with rapidly developing a vaccine for the coronavirus, and would be a very pious act. This is even according to the stricter opinion, since the level of risk for those in such a study is relatively low — only young, healthy people are accepted, and they receive careful medical oversight — and because everyone in the world is at risk for contracting the coronavirus; despite the study, they already were at some risk just by living in society. Entering the study simply makes it happen in a controlled setting and can significantly benefit the entire society, and thus is a mitzvah.

The Jewish community should endorse such protocols, and if a Jew has the opportunity to enter such a study, he or she should enthusiastically do so.

Rabbi Jason Weiner is senior rabbi and director of spiritual care at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.