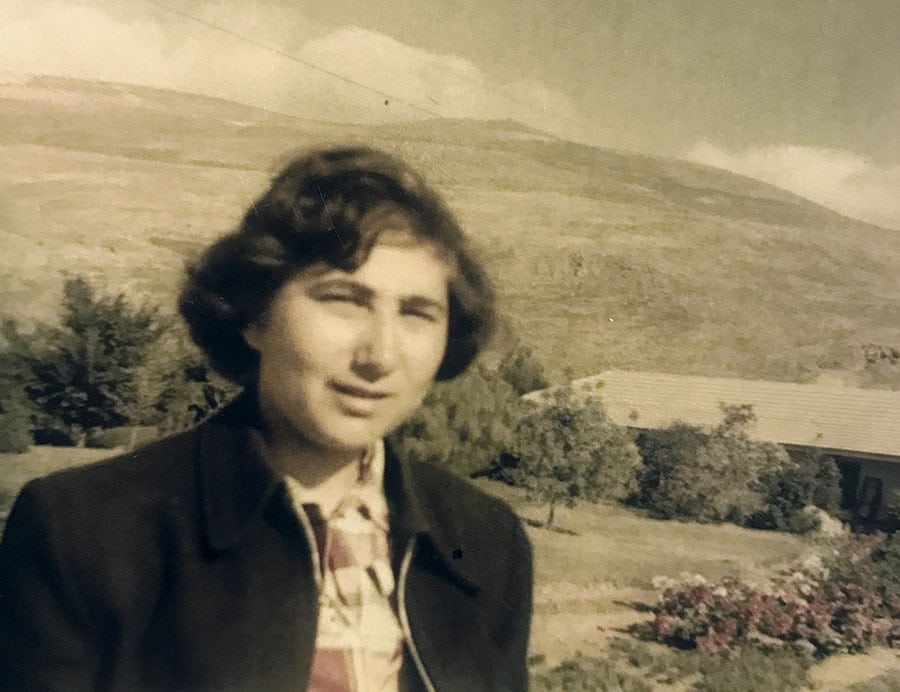

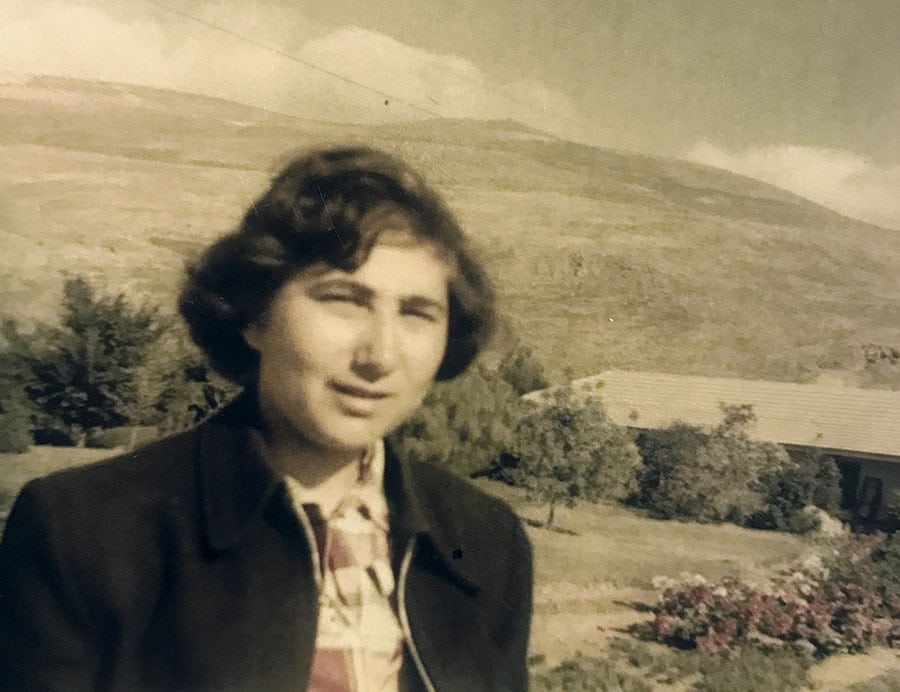

As I finish the year-long mourning period for my mother, Elaine Gerson Troy, I’m trying to integrate all the anecdotes, images and one-liners we have shared into a coherent story and viewpoint. When she died, it was unnerving to see this three-dimensional person reduced to tidbits, fleeting memories. This has been a year of reconstruction, trying to understand what her life meant and can mean for her children, her grandchildren and her yet-to-be-born great-grandchildren.

Philosophically, history vindicated her passionate Zionism but repudiated her pick-and-choose Judaism. My two brothers and I represent a vast historical experiment that mostly flopped: mid-twentieth-century Conservative Judaism.

We were raised in the Conservative Movement, America’s dominant Jewish denomination, with more than 40% of American Jews identifying with “the movement” for decades. We studied in Solomon Schechter Day School and “davened” in a Conservative shul — knowing that only fancy-pants goyishe Jews called it “Temple.” Our father earned a Masters’ from the Jewish Theological Seminary. Both our parents taught at Conservative Hebrew Schools. These were remarkable institutions, filled with loving, thoughtful, proud, passionate, literate Jews — and I honor the rabbis and teachers and lay leaders who shaped us.

But for all that institutional richness, something misfired. As we got older, my mother obsessed about this one who never married, the many who intermarried and that one who no longer spoke to the family. I realize now these stories were blasts of anxiety — and “don’t you dare” flares. My parents had bought into the Conservative bargain: they thought they could create an American shtetl, raising their kids to fulfill the American dream while maintaining some nice Jewish traditions that fit modern life. But life kept showing them their model was not sustainable from generation to generation. The lightweight Judaism most Conservative Jews chose to absorb lacked enough gravity to anchor kids and grandkids increasingly distanced from an immigrant’s foreignness.

Conservative Judaism Americanized the Enlightenment teachings of Moses Mendelssohn and Y.L. Gordon — be a person on the street and a Jew in your home — essentially saying: Be an American on the street and a Jew in your home. The attempt to be a “European on the street” had ended in Zyklon B, but America was different. American Jew-hatred is milder than the European or Muslim strains. Most American Jews could fit in. Our collective attempt to be “American on the Streets” succeeded beyond our wildest dreams, but it mass-produced a Jewish nightmare.

In fairness, we tried outrunning powerful historical forces. Back in the nineteenth-century, the French aristocrat Alexis de Tocqueville described Americans’ zeal for the new, their passion for individualism “which disposes each citizen to isolate himself” and the surprising conformity such seeming autonomy produces. Public opinion, the American Way of Life — capital AWOL — dominated.

Especially for immigrants, America’s great promise — to escape from Old World miseries to New World freedoms and luxuries — aimed a wrecking ball at the ancient ways and preservationist sensibilities Judaism cherishes. In 1938, the historian Marcus Lee Hansen claimed that third-generation immigrants returned to tradition, explaining: “what the son wishes to forget, the grandson wishes to remember.” In fact, what the children wished to forget, the great-grandchildren can barely remember — and much of what the children didn’t even know they knew, the great-grandchildren will never know.

True, the civil rights movement, Israel’s Six-Day War and the Soviet Jewry movement stirred Jewish pride and brought some Jews “back” — as American Jews like to say in the community’s obsessive accounting of who stuck and who folded. However, the sixties’ cultural revolutions ultimately accelerated change and annihilated tradition. All that liberating iconoclasm opened up pathways for more traditional Jews to be visibly Jewish and for less traditional Jews to engineer creative Jewish offshoots, even as most Jews rushed into Americanization’s smothering identity embrace.

Amid this cursed blessing, liberal Judaism, including Conservative Judaism, neutered the most powerful forces that historically kept Jews Jewish. Worshipping their new promised land, lay Conservative Jews turned binding Jewish law into pick-and-choose Jewish folk-law. Judaism’s systematic way of life suddenly offered a smorgasbord, not a predetermined menu. God became a pen pal at best, never a police officer nor a higher authority.

The key question remains: what’s your Jewish motherboard, your non-negotiable, your red line, your identity anchor?

We were Jewish Jugglers par excellence: Many were “Kosher inside the house — unkosher outside;” the more “religious” ones were “McDonald’s Filet-O-Fish kosher,” meaning you’ll eat vegetarian or non-seafood fish anywhere. On Shabbat — we did the dos but didn’t do the don’ts.

When it came to prayer, we learned communal singing, not what it means to commune with God. As for God, He — or She — was MIA. (One rabbi told me that his bar-and-bat mitzvah kids usually believed in God, but their parents didn’t; so by 16, the kids caught up).

Conservative Judaism schooled us in basic Americanism: treating religion as voluntary, pragmatic, almost transactional. These elective traditions were nice, fun, lovely, meaningful; consecrated by history, but obviously not sanctified by God. Words like holiness, sanctity, spirit, soul, even belief, were exotic strangers in our homes, schools, and synagogues. Instead of coming from up high, all our nice, harmless, rarely soul-stretching activities came from that vague non-binding thing Tevye sang about: TRADITION!

In the 1986 American Jewish Yearbook, the Conservative rabbi and scholar Abraham Karp described the movement as blending “Orthodoxy’s devotion to tradition with the open-mindedness of Reform” while remaining the “guardian of authentic traditionalism.” Karp feared the movement’s fatal flaw: “Having its historic origins as a protest against both the excesses of Reform and the insularity of Orthodoxy, Conservative Judaism has suffered from the same malady as other protest movements: Strong in negation, imprecise in affirmation.”

Karp was half-right. We mocked the mawkishness, not just the mushiness. Conservative Judaism offered more American suburban shtick than genuine Jewish substance.

Most Conservative Jews stopped juggling — the contradictions were too glaring, the headwinds toward full Americanism too strong. Like most second- and third-generation American immigrants, we forged ahead, leaving behind our exotic affiliations and rites. We didn’t yet know the buzzword “otherizing,” we just knew instinctively how to pass as “normal.”

Demographics don’t lie: the vast majority of Conservative Jews left Conservatism for Reform or joined the growing ranks of the “unaffiliated.” By 2006, 33% of Americans Jews identified as Conservative Jews — by 2017, it was 16 percent. The Reform movement hovered steadily around 30%, with the Conservative inflow obscuring the Reform-born outflow. 70% of non-Orthodox marriages involved non-Jews.

I take no joy in charting this collapse nor judging anyone’s personal choices. I hope an unsentimental historical accounting can challenge us to learn from ideological mistakes already made while suggesting alternative paths.

My path to stricter observance was not from some leap of faith. It was a series of baby-steps. In sixth grade, I learned in Mrs. Glatzer’s Torah class that eating unkosher is “an abomination.” I instantly shifted from the occasional guiltless lobster to McDonald’s Filet-O-Fish kosher and never again ate anything the Torah designates unkosher.

When I hit graduate school and realized I could always be working ‘round the clock, I embraced my first Shabbat “don’t.” I stopped working on Saturday, including not reading American history books, even though, technically, you could read anything.

Only when we had kids did our family become fully Shomer Shabbat. Even then my Conservative utilitarianism kicked in. I would tell my unnerved friends: “it’s a great family unifier! We have a 25-hour-break from electronics — and fights about electronics!”

My brothers became Orthodox in their teens. I still don’t use that label: I prefer “traditional” – Orthodoxy feels suffocating.

Philosophically, rather than having an “aha” moment, I gradually had an “uh-oh” moment. I saw that Judaism is like a skyscraper — without an unshakeable foundation, it will collapse; that Judaism is like a marriage — without a core, non-negotiable commitment to keeping it going, it’s unsustainable; and that Judaism is like the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine — without keeping it (mostly) in a deep-freeze, it spoils and cannot be passed on.

The Troy family’s countercultural enterprise involved keeping our Jewish identities rock solid – while mastering modernity too. So what made my parents’ Judaism different? Why did their three kids double-down on Judaism, embracing God, commitment, Jewish rigor?

I found the answer in a letter I discovered after my mother’s death, from May 29, 1952, as she sailed home from a year in Israel. In Genoa, she and another young woman stumbled into the red-light district crawling with American sailors. “We were pretty stupid,” she confessed. “At first, I didn’t realize where we were. As soon as we did, we crossed over and started coming back to the boat. Suddenly out of nowhere two boys pop up and asked us if we were from Israel. We said yes and then all started jabbering in Hebrew — it was great. They had seen me in Tel-Aviv and recognized me, so they came over to warn us that we weren’t walking in the ‘right’ section of town. That, we could have told him!

“It’s amazing,” my then-19-year-old mother concluded, “how wherever you go, you always manage to run into a Jew. It’s really the greatest…. Well, they saw that we got back to the boat safely and we’re more convinced than ever that the Jews are the greatest.”

My mother was not just a people person but a peoplehood person. Her blood was blue-and-white — neither red nor red, white, and blue. She and my father were “Orthodox” in their commitment to the Jewish people and what I call Identity Zionism. They bonded when they met in 1954 as among the few American Jewish weirdos who had spent a year in Israel back then. My mother walked down the aisle to the Zionist ballad “Al Sfat Yam Kinneret” (“By the Sea of Galilee”). Sixty-five years later, she asked on her deathbed that we soothe her by singing “David Melech Yisrael” (“David King of Israel”), and “Hatikvah,” Israel’s national anthem.

Peoplehood, Israel and Zionism were all cemented into their foundation stone; they passed that non-negotiable to us. Their Zionism made them stick out, even in our Queens ghetto. Alas, then, as now, “doing Jewish” seriously was insanely expensive. They chose to drive second-hand cars, clothe us in hand-me-downs, never winter in Florida and have no-college-fund because they bankrupted themselves sending us to Solomon Schechter School on teachers’ salaries. Our small house overflowed with Jewish books and tchotchkes — Jew-veneirs. Each book connected us to the great Jewish ideas and values and debates that continue to shape us; each Jewish artifact, no matter how kitschy, stamped our house as different, as living in the 5730s, 40s, and 50s, not just the 1970s, 80s, and 90s.

The one place that never felt cramped in our house was the dining room table. No matter how many of our friends showed up at the last minute, we always found extra room — and more than enough food. From that Jewish flying saucer, we time-traveled and Continent-hopped, perpetually taking off and landing on Jewish concerns, teachings, traditions and challenges.

People sometimes ask me why I became a historian. I answer: “How could I not!” I was steeped in two proud, wonderful, inspiring histories — American and Jewish. I counted in decades as an American — and in millennia as a Jew. Yes, each history had its fault lines; but both stories showed how high ideals can overcome people’s most base behaviors, from American racism to non-Jews’ anti-Semitism.

History was palpable in our house — real, compelling, and binding. Jewish peoplehood was too. Jewish holidays were all historical. Our greatest stories and debates rarely started in the here-and-now. They usually connected to some sweeping phenomenon or narrative. We learned Percy Bysshe Shelley’s “Ozymandias” in school, looking at that “King of Kings’” words, sobered that “Nothing beside remains. Round the decay/Of that colossal Wreck….” But we lived Yehuda Amichai’s 1968 poem, long before we read it: “All the generations before me donated me/Little by little…. My name is my donor’s name. It obligates” — in Hebrew zeh mechiyev.

My parents absorbed decades’ worth of snubs for being too Jewishly-provincial, not trendy, flashy or wealthy enough. They only became respectable to neighboring social-climbers’ eyes, when their “boys” hit American grand slams — Ivy League Educations, advanced graduate degrees, prestigious jobs, CVs branded with magical names from the “real world” — Harvard-Cornell-Columbia-University-of-Texas-McGill, Department-of-Justice-Department-of-Health-and-Human-Services… the White House itself.

As we climbed our respective career ladders, we felt grounded by our rock-solid Jewish commitments, which could only grow because of our solid foundation. My parents’ intense Identity Zionism flowed over, sweeping us up in an ever-growing swirl of Jewish commitments that cascaded, landing one of us – the least pious but the most patriotic Jewishly — in Israel.

My parents modeled a wonderful teaching of the “Rav.” Rabbi Joseph Soloveitchik explained that converts first join the Jewish people’s covenant of fate, “brit goral,” and eventually join Judaism’s covenant of belief, of destiny, of Torah, “brit ye’ud.” So, first, you need a leap of empathy — asking the question Natan Sharansky asked the candidates vying to succeed him at the Jewish Agency: “Do you love the Jewish people?” Then comes the “leap of faith.”

For Judaism really to work, it takes both leaps — that’s our uniqueness, our mix of religion and peoplehood. But to stay Jewish and pass it on in some robust form, you need at least one big, bold, thoroughly Jewish leap.

Amid mid-century America’s obsessively-conformist culture, my parents’ off-beatedness reinforced our unconventional Jewish identities. Traditionally, Jewish identity had a hard shell of what we now call Orthodoxy — which they called “Judaism” — reinforced by a hard shell of Jew-hatred — which they called “life.” You were in or out, which was why so many who left back then vanished, making the Conservative Jewish half-way house unique.

Especially in America-the-seductive, deep Jewish commitments are like oysters’ pearls. They need some grit to be produced. In the blessed absence of anti-Semitism, the great American sin — sticking out — worked. So too does remaining spiritual in a materialistic world and remaining bound by commandments in American-culture’s gravity-free zone.

By contrast, today’s “Tikun Olamers” all too often blur their Jewishness with their liberalism. The results speak for themselves, especially on college campuses. Much of the next generation arrives radically inclusive but often either ignorant or uninterested in Judaism, which doesn’t seem to add much to their identity mix. Occasionally attaching a Biblical verse or traditional value to a partisan position you already embraced treats our 3,900-year-old civilization as a series of punchlines, not a serious philosophy or systemic way of life.

By contrast, the small percentage of non-Orthodox Jews who arrive on campus with some version of Pilates Judaism — strengthened at their core by a leap of empathy or a leap of faith –remain anchored. It’s not surprising that many young Israel activists today have Israeli or Russian names — for many Israeli and Russian families, being Jewish and proud and pro-Israel is not negotiable, not matter how unpopular.

That need for a Blue-and-White bottom line is forcing me to reconsider the light-touch educational strategy I have long advocated. Ironically, even Conservatives’ mushy Judaism acquired a reputation as heavy-handed — because so many Conservative rabbis and parents went full Tevye on young adults when they intermarried. Those of us involved in Birthright Israel counter-programmed, inviting young Jews to leave guilt-trips aside and launch their own Jewish journeys. But we should add a warning that the “I’m-OK-You’re-OK-Jewish-express” is headed nowhere. Jewish identity-building should be more than merely working in a few Jewish fragments into your otherwise full and busy “real” life. Judaism without a core is meaningless and pointless, like a computer without a motherboard.

Similarly, with the ongoing intermarriage debate, delegitimizing people’s love-choices only backfires. But for all my mother’s hand-wringing about who was and wasn’t marrying whom, my parents didn’t do Jewish so we would remain Jewish, they did Jewish because they were Jewish. They taught us to live Jewishly-forward, not reverse engineer; commitments compel continuity. They ensured our Jewish future by living a rich Jewish present. That is why programs fighting against intermarriage have rarely succeeded. Instead, we need more programs like Birthright Israel, boosting Jewish life affirmatively not defensively and sidestepping the intermarriage debate. Young people must draw their own conclusions — not that I shouldn’t intermarry but I couldn’t intermarry, because I wish to build a Jewish home and two partners involved in this holy work are better than one.

In Biblical terms, it was Conservative Judaism’s godlessness that failed; our God was never jealous but flexible, eminently adaptable. We were too rationalist for true belief, too American for true 24/7, 365 days-a-year, take-a-bullet-for-the-Jewish-people solidarity.

Twenty years in Canada exposed me to a Jewish community defined by the leap of empathy and hard-core Jewish commitments. The Montreal Jewish community, in particular, faces more anti-Semitism and Canadian multiculturalism than American melting pottery. With many community members closer to the immigrant experience from a Holocaust-scarred Europe or a once-Jew-hostile Morocco, with dramatically higher percentages of Jewish kids in day schools and with intense intra-communal cohesion, Montreal Jews are more likely to be passionate Jewish patriots, committed Zionists and grandparents of fully-Jewish babies than their American peers.

I’m well aware of Orthodoxy’s blind spots, which is why I bridle at the term. Jealous God yes; zealous God — and zealots for God — no. My mother detested “chnyuks” — self-righteous Orthodox Jews whose commitment to the letter of the law often trumped what was most important to my mother — “menschlechkeit,” acting righteously, humbly, sensitively. And I’m acutely aware that in fulfilling my parents’ Zionist dream by living in Israel, I broke their hearts by living away from them.

In their ideological successes and failures, my parents’ legacy challenges all modern Jews with the fundamental questions of modern Jewish identity: how can we change enough to keep up as moderns but not so much we get lost as Jews? The key question ultimately remains: what’s your Jewish motherboard, your non-negotiable, your red line, your identity anchor? For some it’s God, for others, it’s peoplehood. Without a cemented foundation, without a leap of faith or empathy, no Jewish identity can survive, resisting modernity’s lures to provide the continuity we seek — and the pathways to meaning we all deserve.

Recently designated one of Algemeiner’s J-100, one of the top 100 people “positively influencing Jewish life,” Gil Troy is a Distinguished Scholar of North American History at McGill University, and the author of nine books on American History and three books on Zionism. His book, “Never Alone: Prison, Politics and My People,” co-authored with Natan Sharansky, was just published by PublicAffairs of Hachette.

The Non-Negotiable Judaism My Parents Gave Me

Gil Troy

As I finish the year-long mourning period for my mother, Elaine Gerson Troy, I’m trying to integrate all the anecdotes, images and one-liners we have shared into a coherent story and viewpoint. When she died, it was unnerving to see this three-dimensional person reduced to tidbits, fleeting memories. This has been a year of reconstruction, trying to understand what her life meant and can mean for her children, her grandchildren and her yet-to-be-born great-grandchildren.

Philosophically, history vindicated her passionate Zionism but repudiated her pick-and-choose Judaism. My two brothers and I represent a vast historical experiment that mostly flopped: mid-twentieth-century Conservative Judaism.

We were raised in the Conservative Movement, America’s dominant Jewish denomination, with more than 40% of American Jews identifying with “the movement” for decades. We studied in Solomon Schechter Day School and “davened” in a Conservative shul — knowing that only fancy-pants goyishe Jews called it “Temple.” Our father earned a Masters’ from the Jewish Theological Seminary. Both our parents taught at Conservative Hebrew Schools. These were remarkable institutions, filled with loving, thoughtful, proud, passionate, literate Jews — and I honor the rabbis and teachers and lay leaders who shaped us.

But for all that institutional richness, something misfired. As we got older, my mother obsessed about this one who never married, the many who intermarried and that one who no longer spoke to the family. I realize now these stories were blasts of anxiety — and “don’t you dare” flares. My parents had bought into the Conservative bargain: they thought they could create an American shtetl, raising their kids to fulfill the American dream while maintaining some nice Jewish traditions that fit modern life. But life kept showing them their model was not sustainable from generation to generation. The lightweight Judaism most Conservative Jews chose to absorb lacked enough gravity to anchor kids and grandkids increasingly distanced from an immigrant’s foreignness.

Conservative Judaism Americanized the Enlightenment teachings of Moses Mendelssohn and Y.L. Gordon — be a person on the street and a Jew in your home — essentially saying: Be an American on the street and a Jew in your home. The attempt to be a “European on the street” had ended in Zyklon B, but America was different. American Jew-hatred is milder than the European or Muslim strains. Most American Jews could fit in. Our collective attempt to be “American on the Streets” succeeded beyond our wildest dreams, but it mass-produced a Jewish nightmare.

In fairness, we tried outrunning powerful historical forces. Back in the nineteenth-century, the French aristocrat Alexis de Tocqueville described Americans’ zeal for the new, their passion for individualism “which disposes each citizen to isolate himself” and the surprising conformity such seeming autonomy produces. Public opinion, the American Way of Life — capital AWOL — dominated.

Especially for immigrants, America’s great promise — to escape from Old World miseries to New World freedoms and luxuries — aimed a wrecking ball at the ancient ways and preservationist sensibilities Judaism cherishes. In 1938, the historian Marcus Lee Hansen claimed that third-generation immigrants returned to tradition, explaining: “what the son wishes to forget, the grandson wishes to remember.” In fact, what the children wished to forget, the great-grandchildren can barely remember — and much of what the children didn’t even know they knew, the great-grandchildren will never know.

True, the civil rights movement, Israel’s Six-Day War and the Soviet Jewry movement stirred Jewish pride and brought some Jews “back” — as American Jews like to say in the community’s obsessive accounting of who stuck and who folded. However, the sixties’ cultural revolutions ultimately accelerated change and annihilated tradition. All that liberating iconoclasm opened up pathways for more traditional Jews to be visibly Jewish and for less traditional Jews to engineer creative Jewish offshoots, even as most Jews rushed into Americanization’s smothering identity embrace.

Amid this cursed blessing, liberal Judaism, including Conservative Judaism, neutered the most powerful forces that historically kept Jews Jewish. Worshipping their new promised land, lay Conservative Jews turned binding Jewish law into pick-and-choose Jewish folk-law. Judaism’s systematic way of life suddenly offered a smorgasbord, not a predetermined menu. God became a pen pal at best, never a police officer nor a higher authority.

We were Jewish Jugglers par excellence: Many were “Kosher inside the house — unkosher outside;” the more “religious” ones were “McDonald’s Filet-O-Fish kosher,” meaning you’ll eat vegetarian or non-seafood fish anywhere. On Shabbat — we did the dos but didn’t do the don’ts.

When it came to prayer, we learned communal singing, not what it means to commune with God. As for God, He — or She — was MIA. (One rabbi told me that his bar-and-bat mitzvah kids usually believed in God, but their parents didn’t; so by 16, the kids caught up).

Conservative Judaism schooled us in basic Americanism: treating religion as voluntary, pragmatic, almost transactional. These elective traditions were nice, fun, lovely, meaningful; consecrated by history, but obviously not sanctified by God. Words like holiness, sanctity, spirit, soul, even belief, were exotic strangers in our homes, schools, and synagogues. Instead of coming from up high, all our nice, harmless, rarely soul-stretching activities came from that vague non-binding thing Tevye sang about: TRADITION!

In the 1986 American Jewish Yearbook, the Conservative rabbi and scholar Abraham Karp described the movement as blending “Orthodoxy’s devotion to tradition with the open-mindedness of Reform” while remaining the “guardian of authentic traditionalism.” Karp feared the movement’s fatal flaw: “Having its historic origins as a protest against both the excesses of Reform and the insularity of Orthodoxy, Conservative Judaism has suffered from the same malady as other protest movements: Strong in negation, imprecise in affirmation.”

Karp was half-right. We mocked the mawkishness, not just the mushiness. Conservative Judaism offered more American suburban shtick than genuine Jewish substance.

Most Conservative Jews stopped juggling — the contradictions were too glaring, the headwinds toward full Americanism too strong. Like most second- and third-generation American immigrants, we forged ahead, leaving behind our exotic affiliations and rites. We didn’t yet know the buzzword “otherizing,” we just knew instinctively how to pass as “normal.”

Demographics don’t lie: the vast majority of Conservative Jews left Conservatism for Reform or joined the growing ranks of the “unaffiliated.” By 2006, 33% of Americans Jews identified as Conservative Jews — by 2017, it was 16 percent. The Reform movement hovered steadily around 30%, with the Conservative inflow obscuring the Reform-born outflow. 70% of non-Orthodox marriages involved non-Jews.

I take no joy in charting this collapse nor judging anyone’s personal choices. I hope an unsentimental historical accounting can challenge us to learn from ideological mistakes already made while suggesting alternative paths.

My path to stricter observance was not from some leap of faith. It was a series of baby-steps. In sixth grade, I learned in Mrs. Glatzer’s Torah class that eating unkosher is “an abomination.” I instantly shifted from the occasional guiltless lobster to McDonald’s Filet-O-Fish kosher and never again ate anything the Torah designates unkosher.

When I hit graduate school and realized I could always be working ‘round the clock, I embraced my first Shabbat “don’t.” I stopped working on Saturday, including not reading American history books, even though, technically, you could read anything.

Only when we had kids did our family become fully Shomer Shabbat. Even then my Conservative utilitarianism kicked in. I would tell my unnerved friends: “it’s a great family unifier! We have a 25-hour-break from electronics — and fights about electronics!”

My brothers became Orthodox in their teens. I still don’t use that label: I prefer “traditional” – Orthodoxy feels suffocating.

Philosophically, rather than having an “aha” moment, I gradually had an “uh-oh” moment. I saw that Judaism is like a skyscraper — without an unshakeable foundation, it will collapse; that Judaism is like a marriage — without a core, non-negotiable commitment to keeping it going, it’s unsustainable; and that Judaism is like the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine — without keeping it (mostly) in a deep-freeze, it spoils and cannot be passed on.

The Troy family’s countercultural enterprise involved keeping our Jewish identities rock solid – while mastering modernity too. So what made my parents’ Judaism different? Why did their three kids double-down on Judaism, embracing God, commitment, Jewish rigor?

I found the answer in a letter I discovered after my mother’s death, from May 29, 1952, as she sailed home from a year in Israel. In Genoa, she and another young woman stumbled into the red-light district crawling with American sailors. “We were pretty stupid,” she confessed. “At first, I didn’t realize where we were. As soon as we did, we crossed over and started coming back to the boat. Suddenly out of nowhere two boys pop up and asked us if we were from Israel. We said yes and then all started jabbering in Hebrew — it was great. They had seen me in Tel-Aviv and recognized me, so they came over to warn us that we weren’t walking in the ‘right’ section of town. That, we could have told him!

“It’s amazing,” my then-19-year-old mother concluded, “how wherever you go, you always manage to run into a Jew. It’s really the greatest…. Well, they saw that we got back to the boat safely and we’re more convinced than ever that the Jews are the greatest.”

My mother was not just a people person but a peoplehood person. Her blood was blue-and-white — neither red nor red, white, and blue. She and my father were “Orthodox” in their commitment to the Jewish people and what I call Identity Zionism. They bonded when they met in 1954 as among the few American Jewish weirdos who had spent a year in Israel back then. My mother walked down the aisle to the Zionist ballad “Al Sfat Yam Kinneret” (“By the Sea of Galilee”). Sixty-five years later, she asked on her deathbed that we soothe her by singing “David Melech Yisrael” (“David King of Israel”), and “Hatikvah,” Israel’s national anthem.

Peoplehood, Israel and Zionism were all cemented into their foundation stone; they passed that non-negotiable to us. Their Zionism made them stick out, even in our Queens ghetto. Alas, then, as now, “doing Jewish” seriously was insanely expensive. They chose to drive second-hand cars, clothe us in hand-me-downs, never winter in Florida and have no-college-fund because they bankrupted themselves sending us to Solomon Schechter School on teachers’ salaries. Our small house overflowed with Jewish books and tchotchkes — Jew-veneirs. Each book connected us to the great Jewish ideas and values and debates that continue to shape us; each Jewish artifact, no matter how kitschy, stamped our house as different, as living in the 5730s, 40s, and 50s, not just the 1970s, 80s, and 90s.

The one place that never felt cramped in our house was the dining room table. No matter how many of our friends showed up at the last minute, we always found extra room — and more than enough food. From that Jewish flying saucer, we time-traveled and Continent-hopped, perpetually taking off and landing on Jewish concerns, teachings, traditions and challenges.

People sometimes ask me why I became a historian. I answer: “How could I not!” I was steeped in two proud, wonderful, inspiring histories — American and Jewish. I counted in decades as an American — and in millennia as a Jew. Yes, each history had its fault lines; but both stories showed how high ideals can overcome people’s most base behaviors, from American racism to non-Jews’ anti-Semitism.

History was palpable in our house — real, compelling, and binding. Jewish peoplehood was too. Jewish holidays were all historical. Our greatest stories and debates rarely started in the here-and-now. They usually connected to some sweeping phenomenon or narrative. We learned Percy Bysshe Shelley’s “Ozymandias” in school, looking at that “King of Kings’” words, sobered that “Nothing beside remains. Round the decay/Of that colossal Wreck….” But we lived Yehuda Amichai’s 1968 poem, long before we read it: “All the generations before me donated me/Little by little…. My name is my donor’s name. It obligates” — in Hebrew zeh mechiyev.

My parents absorbed decades’ worth of snubs for being too Jewishly-provincial, not trendy, flashy or wealthy enough. They only became respectable to neighboring social-climbers’ eyes, when their “boys” hit American grand slams — Ivy League Educations, advanced graduate degrees, prestigious jobs, CVs branded with magical names from the “real world” — Harvard-Cornell-Columbia-University-of-Texas-McGill, Department-of-Justice-Department-of-Health-and-Human-Services… the White House itself.

As we climbed our respective career ladders, we felt grounded by our rock-solid Jewish commitments, which could only grow because of our solid foundation. My parents’ intense Identity Zionism flowed over, sweeping us up in an ever-growing swirl of Jewish commitments that cascaded, landing one of us – the least pious but the most patriotic Jewishly — in Israel.

My parents modeled a wonderful teaching of the “Rav.” Rabbi Joseph Soloveitchik explained that converts first join the Jewish people’s covenant of fate, “brit goral,” and eventually join Judaism’s covenant of belief, of destiny, of Torah, “brit ye’ud.” So, first, you need a leap of empathy — asking the question Natan Sharansky asked the candidates vying to succeed him at the Jewish Agency: “Do you love the Jewish people?” Then comes the “leap of faith.”

For Judaism really to work, it takes both leaps — that’s our uniqueness, our mix of religion and peoplehood. But to stay Jewish and pass it on in some robust form, you need at least one big, bold, thoroughly Jewish leap.

Amid mid-century America’s obsessively-conformist culture, my parents’ off-beatedness reinforced our unconventional Jewish identities. Traditionally, Jewish identity had a hard shell of what we now call Orthodoxy — which they called “Judaism” — reinforced by a hard shell of Jew-hatred — which they called “life.” You were in or out, which was why so many who left back then vanished, making the Conservative Jewish half-way house unique.

Especially in America-the-seductive, deep Jewish commitments are like oysters’ pearls. They need some grit to be produced. In the blessed absence of anti-Semitism, the great American sin — sticking out — worked. So too does remaining spiritual in a materialistic world and remaining bound by commandments in American-culture’s gravity-free zone.

By contrast, today’s “Tikun Olamers” all too often blur their Jewishness with their liberalism. The results speak for themselves, especially on college campuses. Much of the next generation arrives radically inclusive but often either ignorant or uninterested in Judaism, which doesn’t seem to add much to their identity mix. Occasionally attaching a Biblical verse or traditional value to a partisan position you already embraced treats our 3,900-year-old civilization as a series of punchlines, not a serious philosophy or systemic way of life.

By contrast, the small percentage of non-Orthodox Jews who arrive on campus with some version of Pilates Judaism — strengthened at their core by a leap of empathy or a leap of faith –remain anchored. It’s not surprising that many young Israel activists today have Israeli or Russian names — for many Israeli and Russian families, being Jewish and proud and pro-Israel is not negotiable, not matter how unpopular.

That need for a Blue-and-White bottom line is forcing me to reconsider the light-touch educational strategy I have long advocated. Ironically, even Conservatives’ mushy Judaism acquired a reputation as heavy-handed — because so many Conservative rabbis and parents went full Tevye on young adults when they intermarried. Those of us involved in Birthright Israel counter-programmed, inviting young Jews to leave guilt-trips aside and launch their own Jewish journeys. But we should add a warning that the “I’m-OK-You’re-OK-Jewish-express” is headed nowhere. Jewish identity-building should be more than merely working in a few Jewish fragments into your otherwise full and busy “real” life. Judaism without a core is meaningless and pointless, like a computer without a motherboard.

Similarly, with the ongoing intermarriage debate, delegitimizing people’s love-choices only backfires. But for all my mother’s hand-wringing about who was and wasn’t marrying whom, my parents didn’t do Jewish so we would remain Jewish, they did Jewish because they were Jewish. They taught us to live Jewishly-forward, not reverse engineer; commitments compel continuity. They ensured our Jewish future by living a rich Jewish present. That is why programs fighting against intermarriage have rarely succeeded. Instead, we need more programs like Birthright Israel, boosting Jewish life affirmatively not defensively and sidestepping the intermarriage debate. Young people must draw their own conclusions — not that I shouldn’t intermarry but I couldn’t intermarry, because I wish to build a Jewish home and two partners involved in this holy work are better than one.

In Biblical terms, it was Conservative Judaism’s godlessness that failed; our God was never jealous but flexible, eminently adaptable. We were too rationalist for true belief, too American for true 24/7, 365 days-a-year, take-a-bullet-for-the-Jewish-people solidarity.

Twenty years in Canada exposed me to a Jewish community defined by the leap of empathy and hard-core Jewish commitments. The Montreal Jewish community, in particular, faces more anti-Semitism and Canadian multiculturalism than American melting pottery. With many community members closer to the immigrant experience from a Holocaust-scarred Europe or a once-Jew-hostile Morocco, with dramatically higher percentages of Jewish kids in day schools and with intense intra-communal cohesion, Montreal Jews are more likely to be passionate Jewish patriots, committed Zionists and grandparents of fully-Jewish babies than their American peers.

I’m well aware of Orthodoxy’s blind spots, which is why I bridle at the term. Jealous God yes; zealous God — and zealots for God — no. My mother detested “chnyuks” — self-righteous Orthodox Jews whose commitment to the letter of the law often trumped what was most important to my mother — “menschlechkeit,” acting righteously, humbly, sensitively. And I’m acutely aware that in fulfilling my parents’ Zionist dream by living in Israel, I broke their hearts by living away from them.

In their ideological successes and failures, my parents’ legacy challenges all modern Jews with the fundamental questions of modern Jewish identity: how can we change enough to keep up as moderns but not so much we get lost as Jews? The key question ultimately remains: what’s your Jewish motherboard, your non-negotiable, your red line, your identity anchor? For some it’s God, for others, it’s peoplehood. Without a cemented foundation, without a leap of faith or empathy, no Jewish identity can survive, resisting modernity’s lures to provide the continuity we seek — and the pathways to meaning we all deserve.

Recently designated one of Algemeiner’s J-100, one of the top 100 people “positively influencing Jewish life,” Gil Troy is a Distinguished Scholar of North American History at McGill University, and the author of nine books on American History and three books on Zionism. His book, “Never Alone: Prison, Politics and My People,” co-authored with Natan Sharansky, was just published by PublicAffairs of Hachette.

Did you enjoy this article?

You'll love our roundtable.

Editor's Picks

Israel and the Internet Wars – A Professional Social Media Review

The Invisible Student: A Tale of Homelessness at UCLA and USC

What Ever Happened to the LA Times?

Who Are the Jews On Joe Biden’s Cabinet?

You’re Not a Bad Jewish Mom If Your Kid Wants Santa Claus to Come to Your House

No Labels: The Group Fighting for the Political Center

Latest Articles

How Israel Consul General Coordinated Synagogue Event Attacked By Protesters

Rabbis of LA | Rabbi Kahn Looks Back on His Two Years Helping Israelis

“Your Children Shall Return To Their Homeland”

Angels are on the Way – A poem for Parsha Vayishlach

Brothers for Life Supports IDF Soldiers, Western Wall Notes, Mayor Nazarian

A Moment in Time: “A Minor Inconvenience”

Enough Is Enough: We Are Running Out of Time to Protect Our Jewish Community

Protecting our community is foundational to Jews feeling safe enough to express our First Amendment rights, like everybody else in America.

When Distance Is Remote

Amy and Nancy Harrington: The Passionistas Project, the Jewish-Italian Connection and Pizza Dolce

Taste Buds with Deb – Episode 135

Jewish Photographer’s Book Will Make You Want To Rock and Roll All Night

“When I was young, I wanted to be Jimmy Page. That job was already taken. So I learned how to work a camera and photographed Jimmy Page.”

Stories of Jewish Heroism and the ‘Yiddish Sherlock Holmes’

These 15 stories by Jonas Kreppel feature the “Yiddish Sherlock Holmes” who saves Jews from various plights within the Austro-Hungarian Empire during the early 20th century.

‘Marty Supreme’: Josh Safdie’s Film About a Relentless Quest for Success

Inspired by real-life Jewish table-tennis legend Marty Reisman, the film traces Marty’s upbringing in the Lower East Side and the intertwined forces of his family identity and fierce ambition that drove him.

A Moroccan Journey — My Father’s Life

The name Messod means blessing and good fortune and my father was fortunate to live a life overflowing with both.

Table for Five: Vayishlach

A Difficult Birth

Days of Hell and Love

A year after meeting on a dating app, Sapir Cohen and Sasha Troufanov were abducted from Kibbutz Nir Oz on Oct. 7, 2023. Cohen spent 55 days in hell under Hamas; Troufanov 498 days under Islamic Jihad. Finally free and reunited, they tell The Journal their story.

When the Plaques Say “Respect” and the Wall Says “Jews Don’t Belong”

Hate against Jews is hate. Say it. Mean it. Enforce it. Or stop pretending this institution has the moral confidence to protect the students in its care.

Print Issue: Days of Hell and Love | December 5, 2025

A year after meeting on a dating app, Sapir Cohen and Sasha Troufanov were abducted from Kibbutz Nir Oz on Oct. 7, 2023. Cohen spent 55 days in hell under Hamas; Troufanov 498 days under Islamic Jihad. Finally free and reunited, they tell The Journal their story.

This is Why I Don’t Do Podcasts ft. Elon Gold

Pro-Palestinian Protest Turns Violent at Wilshire Boulevard Temple Event

The shards of broken glass nearly hit Jolkovsky and others in attendance.

Rosner’s Domain | Bibi’s Pardon: Quid Pro Nothing

The basic question about any deal is simple: does it or doesn’t it include a concrete, enforceable process that marks the end of the Netanyahu era? All other concessions are insignificant.

Revisiting Un-Jews Who Undo the Deepest Jewish Bonds

The “un-Jews” continue to undo timeless Jewish connections.

We Need Real Solutions to Our Housing Crisis, Not the Fool’s Gold of the 50-Year Mortgage

No amount of creative financing can resolve the core issue at the heart of America’s housing crisis: an acute shortage of homes.

Friend or Folly?

The Cantonese-Speaking Hasid and the American Dream

As Silk’s memoir, “A Seat at the Table: An Inside Account of Trump’s Global Economic Revolution,” captivatingly details, his unique story is a testament to the power of faith and the promise of America.

On Hate, Condescension and Political Extremism

To understand the full nature of the political and social rift within Israeli society, it is necessary to explore the realm of emotions.

Feld Entertainment’s Juliette Feld Grossman on Disney on Ice’s Return to LA

“It’s so gratifying to bring families closer together and create these special moments that become lifelong memories.”

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.