Motortion/Getty Images

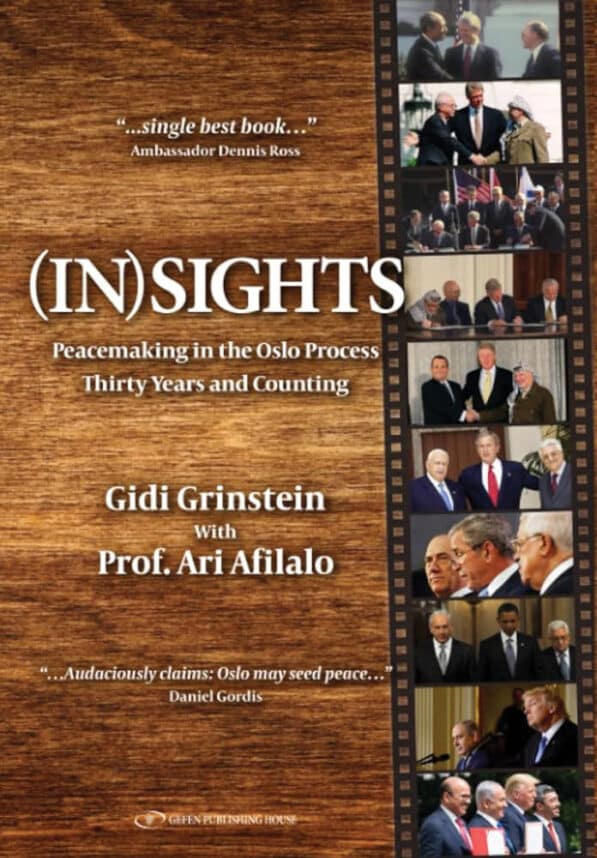

Motortion/Getty Images  “(In)sights: Peacemaking in the Oslo Process” by Gidi Grinstein with Ari Afilalo begins with a quote from the Tanakh, ‘Seek peace and pursue it’ (Tehillim 34:15). It is a powerful verse — made all the more impactful by its simplicity, but just as the Talmud takes a single line of scripture and expands upon its every hidden implication, “(In)sights” reveals the countless complexities, considerations, breakthroughs, liaisons, setbacks, and headaches that come into play when one actually attempts to “seek peace and pursue it” in the real world.

“(In)sights: Peacemaking in the Oslo Process” by Gidi Grinstein with Ari Afilalo begins with a quote from the Tanakh, ‘Seek peace and pursue it’ (Tehillim 34:15). It is a powerful verse — made all the more impactful by its simplicity, but just as the Talmud takes a single line of scripture and expands upon its every hidden implication, “(In)sights” reveals the countless complexities, considerations, breakthroughs, liaisons, setbacks, and headaches that come into play when one actually attempts to “seek peace and pursue it” in the real world.

Many of these messy details will be confounding to anyone who isn’t a career diplomat. Rather than a straightforward set of deliberations on key issues, peacemaking apparently involves public negotiations alongside multiple secret backchannels, negotiators who have been instructed explicitly to stall, and demands engineered to sink the whole process. Instead of dispassionate professionals talking brass tacks at a table, there are often screaming fights and tears.

But through it all, we are told, Grinstein never stopped wearing a certain novelty tie, “classic dark blue with a gentle design of doves,” to important meetings — a striking visual symbol of the Oslo process itself, in which the highest ideals of peace collided with the frustrating realities of politics, power, and compromise.

Thirty years ago, Gidi Grinstein was “the youngest and most junior member” of the Israeli delegation at Camp David — the place where the Oslo peace process came to a dramatic climax and promptly fell apart.

Thirty years ago, Gidi Grinstein was “the youngest and most junior member” of the Israeli delegation at Camp David — the place where the Oslo peace process came to a dramatic climax and promptly fell apart when, seven years after the signing of the first Oslo agreement, PLO leader Yasser Arafat rejected Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Barak’s best offer.

In the years that followed, other members of the delegation would pen their memoirs of the historic peace process, each intent on answering the question on everyone’s mind: “What went wrong?”

That it has taken 30 years for Grinstein to write his own account can be attributed to two reasons. The first is stated explicitly in his book. He was young and “just” the secretary of the delegation, “neither a principal nor a major decision-maker.” As such, coming out with his own analysis could have been interpreted as overstepping boundaries.

“Frankly,” he writes, “I thought it would be bad for my career. Principals do not generally appreciate seconds who document and analyze their actions.”

There is, however, a second unstated reason, which is that he seems fundamentally ambivalent about the purpose of such a book.

Is it a memoir — a personal account of his time in the rooms where world history was being made? Is it a eulogy for a failed vision of peace? Is it an autopsy? Or is it a guidebook for future peacemakers, who will need such a resource when the conditions for negotiations again “ripen”?

The book itself is undecided on this matter. This is by design. “Beyond the historical value of documenting Gidi’s stories,” writes co-author Professor Ari Afilalo, “our book is also designed to support future negotiations.”

By design or not, however, one senses a hesitance in the writing. The book holds back from fully entering into the “narrative” aspects of Grinstein’s story, though it is neither a straightforward book on policy and principles geared towards wonks and visionaries.

In this, I’m reminded of a passage from the Talmud. In a deliberation about the ancient Yom Kippur ritual, the text pauses to ask what purpose there is in pouring over minutia from the past.

One potential solution is offered: We aren’t asking about the past but the future, when the Messiah comes and the Temple Service is restored.

The Talmud rejects this answer. Our learning isn’t for the sake of the past or the future. Rather, it is for the present — so that we, right here and now, can have better understanding and wisdom.

As I read “(In)sights,” I kept this in mind. The book was not quite a tale of the past, nor was it quite a guide for the future. It did, however, help me understand what exactly we are talking about when we talk about the pursuit of peace between Israel and the Palestinians.

The Oslo process unfolded like a quest in a fantasy novel — a desperate search for a magical talisman which, when found, would change the world forever.

The Oslo process unfolded like a quest in a fantasy novel — a desperate search for a magical talisman which, when found, would change the world forever. The name of this much-sought entity was “FAPS,” an inelegant-sounding acronym for “Framework Agreement on Permanent Status.”

In the 90s, the Oslo Accords led to the creation of certain interim arrangements between Israel and the Palestinians. Chief among these was the creation of the Palestinian Authority as the representative political body for the Palestinian population, as well as the division of the West Bank into areas of Palestinian or Israeli control.

These interim arrangements sidestepped crucial outstanding issues, including Palestinian refugees, the status of Jerusalem, security, water, and access to holy sites — leaving all of that for the elusive FAPS, which, when settled upon, would answer all questions and end all disputes.

For anyone who suffers under the misconception that the peace process ought to be simple, the story of the search for a FAPS is a helpful antidote. Securing a peace deal with a stateless population is far more complex than forging peace between two states — as Israel did with Egypt, for instance. After this is settled, there remains a complex web of issues pertaining to security, resources, and recognition.

Grinstein’s book details how the Israeli delegation navigated these matters to arrive at Ehud Barak’s historic offer — a Palestinian state on nearly all of the territory of the West Bank and Gaza with its capital in Jerusalem—an offer that, perhaps shockingly or perhaps predictably, led not to peace, but to the outbreak of terrible violence and the collapse of the peace process itself.

Observers worldwide were (and are) shocked by Arafat’s rejection of this exceedingly “generous” offer. The reason that this is shocking, however, is because we believe that the two-state solution serves the Palestinians’ interests more than Israel’s and that it is therefore something which Israel would grant only begrudgingly.

“It is a paradox that the ultimate achievement for Zionism in securing a territory for the Jewish People hinges on having a bilaterally agreed and internationally recognized border with the Palestinians, with no further claims.”

Grinstein, however, argues that this is not actually the case. Barak’s FAPS would more vitally serve a Jewish/Israeli interest. In creating permanent and final borders for the state of Israel, a FAPS would essentially finish the work of Zionism, making Israel a clearly defined entity whose existence is recognized even by its most avowed enemies. “It is a paradox that the ultimate achievement for Zionism in securing a territory for the Jewish People hinges on having a bilaterally agreed and internationally recognized border with the Palestinians, with no further claims.”

Such a closing of accounts, however, would essentially put an end to the Palestinian national movement’s dream of a Palestinian state in all of Mandatory Palestine.

From this perspective, neither Arafat’s rejection nor Barak’s offer is so shocking. The Palestinians, far from being desperate for an offer, knew that “accepting” statehood meant giving up key leverage.

Grinstein’s account is a tribute to the hardworking individuals who pushed for peace under the leadership of Ehud Barak. It is not, however, without critique of some of the assumptions underlying this process.

One of these is the very idea of making a FAPS the final goal of the peace process. It would have been better, according to Grinstein, to work towards a semi-autonomous Palestinian pseudo-state within provisional borders and then worry about settling the fine details later.

Similar approaches have been popularized in recent years by thinkers like Micah Goodman — the Israeli author who advocates “shrinking the conflict” rather than solving it. By working to reach agreements on small, solvable problems, the occupation can be lessened without having to devise an overarching FAPS that somehow satisfies everyone involved.

Another key assumption of the Oslo process that Grinstein calls into question is the idea that unilateral action should be avoided. Had Arafat followed through on his threat of unilaterally declaring Palestinian independence, Grinstein muses, perhaps that would have been a blessing for the process in the end. Had Israel decided unilaterally on final borders without Palestinian consent, maybe this would have moved things along.

But in 2023, the idea of either unilateral or bilateral peace is likely to raise eyebrows amongst many Israelis. In 2005, Israel unilaterally withdrew from Gaza. Instead of peace, it led to the takeover of the Gaza strip by Hamas and a nonstop cycle of war that lasts to this day. Bilateral agreements, on the other hand, hardly have a better track record. The collapse of Oslo led to the second intifada.

And so the Israeli public has, in many ways, stopped believing that peace is possible. Whether or not this was true at Camp David, the situation is demonstrably worse today.

Today, the Palestinians have no single representative governing body which could negotiate with Israel on their behalf. There is the Palestinian Authority in the West Bank, run by President Mahmoud Abbas of the Fatah party, but there is also the Gaza Strip, dominated by Hamas. Even if Israel did strike up a deal with the PA, the matter of Gaza would remain unsettled.

For its part, Israel is no longer run by the likes of Ehud Barak. Instead, Israel is currently governed by the most right-wing government in its history, replete with ministers who are avowedly pro-annexation and against the formation of a Palestinian state.

The amount of settlers in the West Bank has doubled since the days of the Camp David summit, threatening any future Palestinian state’s contiguity and viability. Also, the trauma of the evacuation of settlers from Gaza in 2005 has transformed the idea of such withdrawals into a political nonstarter. In other words, the Palestinians shouldn’t expect any more offers like they received from Barak in the near future.

This hasn’t fundamentally changed the Palestinian leadership’s expectations, however. Offers of a state on less than 100% of the West Bank and Gaza, like the Trump plan, are not so much as countenanced.

Both sides, according to Grinstein, believe that time is on their side. Sober analysis reveals how deeply untrue this is. Israel is rushing towards a one-state reality that threatens the Zionist dream of a Jewish and democratic state. Palestinians, meanwhile, are holding out for a better offer when no such offer is on the way.

Still, Grinstein is not a pessimist. “Millions of Palestinians and Israelis do not want to share a society and be part of the same nation, effectively rejecting the notion of the current situation in the West Bank as permanent. Their collective energy will, at some point, be transformative.”

When will this happen? Well, Grinstein says we must wait for “ripeness.” When the time is “ripe,” he writes, “hitherto-decades-old insurmountable problems can be creatively resolved in days or hours.” In other words, we must wait — wait for a shift in zeitgeist, a “synchronization of clocks,” a wind of change.

This prognosis reminded me of a Haaretz column from last year by Rogel Alpher titled, “Only a Black Swan Event Will End the Occupation.” The Black Swan theory, created by Nassim Nicholas Taleb, describes rare, unpredictable, and highly impactful events that defy conventional expectations. These events challenge the reliability of historical data and models, emphasizing the need to be prepared for the unexpected.

The column depressed me. It was, if nothing else, a sign that prospects of a peace deal have become so grim that all we can hope for is a vague, nameless, future something. We might as well wish upon a star.

Such events have shifted the course of Israeli history before. Think of the current protest movement or the Abraham Accords. Even the foundation of the state of Israel itself can be considered a Black Swan event.

That said, such events have shifted the course of Israeli history before. Think of the current protest movement or the Abraham Accords. Even the foundation of the state of Israel itself can be considered a Black Swan event.

At some undisclosed point in the future, perhaps another such event will trigger “ripeness.” Something will happen that will make Palestinians decide that the time has come to end their struggle against Israel and build a state. Something will change that will make Israelis realize that a lasting peace is worth more than expanded borders.

Towards the end of his book, Grinstein writes: “Zionism — the outlook that calls for the Jewish People to have a state in the Land of Israel, where it realizes its right of self-determination — has been a Jewish prayer for nearly 1,900 years.”

In truth, the dream goes back even further than that.

We are at a point in our Jewish calendar when we conclude the yearly cycle of Torah readings. The book of Deuteronomy ends with the Israelites poised to enter the promised land — but the narrative drops off before they actually cross that boundary. A week later and we begin again with the creation of the universe.

Readers eager to see the happy ending play out, and to watch the Israelites actually ride off into that sunset, can turn to the book of Joshua. But the book of Joshua is about conquering and dividing the land. In other words, we don’t actually get to see the Israelites settle down into their new homeland. All we see is more seeking, more war, more pain.

Surely, after that, things get easier. But alas, in the book of Judges, we see that the Israelites have not reached stasis. They are continually at war with their neighbors.

By the time we get to the book of Kings, we have tales of foreign empires invading the land, laying siege to the cities, and exiling the Israelites.

There is something terribly upsetting about these narratives. The Israelites have come to the Promised Land to build a society and serve God, but they never quite find material security. Their placement remains precarious. Their situation remains vulnerable. No FAPS — no permanent status — is ever achieved.

Modern history mirrors this story, for both Jews and Palestinians. Both peoples want a final settling of accounts and a laying down of arms, but neither can accede to the full extent of the other’s demands. And so the quest for a FAPS remains forever on the far side of a litany of outstanding issues with no clear solutions.

What I took away from this book is the same lesson I take away from the troubled history of the Israelites portrayed in the Tanakh — namely, that there is an absurdity to the quest for finality, for permanence, for happily ever after. In a world of flux, of clash, of conflict, we are setting ourselves up for failure when we make this our goal.

We dream of permanence, we speak of “never again,” we declare our “eternal capital.” But the truth is that no status is really permanent in this world.

I can’t speak for Palestinians, but I know that this idea is very frightening to Jews. We dream of permanence, we speak of “never again,” we declare our “eternal capital.” But the truth is that no status is really permanent in this world.

Better that we admit it now and take Grinstein’s advice — waiting for the moment to be ripe and then moving forward in a pursuit for provisional peace instead of a FAPS. It’s less idealistic than a novelty tie with doves, but it will have to do.

Matthew Schultz is a Jewish Journal columnist and rabbinical student at Hebrew College. He is the author of the essay collection “What Came Before” (Tupelo, 2020) and lives in Boston and Jerusalem.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.