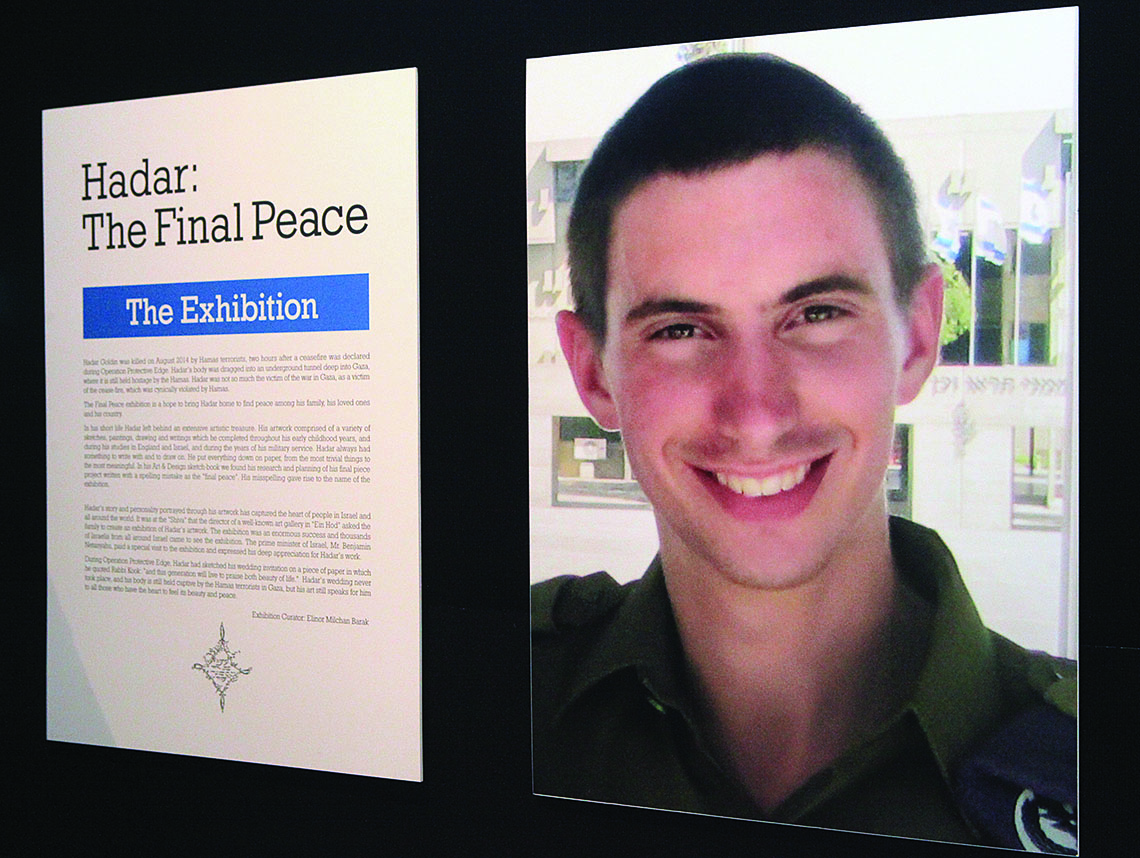

An exhibition of the artwork of Hadar Goldin, who was killed by Hamas in August 2014. Photos by Bart Batholomew/Courtesy of Simon Wiesenthal Center.

An exhibition of the artwork of Hadar Goldin, who was killed by Hamas in August 2014. Photos by Bart Batholomew/Courtesy of Simon Wiesenthal Center. Leah and Simcha Goldin are grieving parents. Frustrated, vocal and driven, they have traveled from the Knesset to the United Nations to, just last week, the Museum of Tolerance in Los Angeles, bringing with them a traveling collection of their son’s artwork known as “Hadar Goldin: The Final Peace” to bring attention to his plight.

“It is our mission to bring Hadar home,” Leah said with a straight-ahead gaze, her voice shrouded in a thick Israeli accent.

Bring Hadar home.

Leah Goldin has uttered those words too many times since August 2014, when her son first went missing.

When Hadar comes home, they will not embrace, as mother and son ought after being separated for so long. There will be a ceremony and, most likely, a press conference. But Hadar’s remains will be in a coffin with an Israeli flag draped over it. A grave will be filled, topped with tilled soil. This is what “Bring Hadar home” means.

Of course, that’s if Hadar comes home. But to Leah, a doctor of computer science, and her husband, Simcha, a professor at Tel Aviv University, there is no “if”: They have dedicated themselves to make sure that day comes.

“Hadar is a victim of a cease-fire, rather than a victim of a war,” his mother said, nearly three years after that breach of cease-fire, which took her son’s life.

On Aug. 1, 2014, after a flare-up of escalations between Israel and Hamas during Operation Protective Edge, then-U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry and then-U.N. Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon announced a 72-hour humanitarian cease-fire. Two hours into that ceasefire, Hamas ambushed Israeli soldiers in the southern border town of Rafas, a raid resulting in Hadar’s death and the kidnapping of his body, which was dragged back to Gaza through a network of underground tunnels. He was a lieutenant in the Israel Defense Forces at the time.

During that summer conflict, the body of staff Sgt. Oron Shaul also was captured. Both bodies are still in Hamas’ custody, and the Goldins want the international community to pressure Hamas for the return of their son’s body.

So it’s through Hadar’s traveling collection of art — with pieces ranging in style from expressionist paintings to daily life sketches to journal entries — that the Goldins hope to make strides on the matter. They first got the idea to put together a collection while sitting shivah for their son, after being approached by art curators from Ein Hod (an artists village near Haifa). “And they advised us to put up an exhibition; we didn’t realize we could do it,” said Leah.

In September, the collection was on view at the United Nations in New York during the General Assembly. “Since this cease-fire was brokered by John Kerry, secretary of state, and Ban Ki-moon, general-secretary of the U.N., they should be held responsible. They should be accountable for his return,” Leah said. Neither Kerry nor Ban came to the exhibition, she said.

“And they knew about the exhibition,” Leah added. “I cannot tell you why they did not want to go. You should ask them.”

“It’s a question of responsibility,” Simcha added.

“And accountability,” Leah said. “Sometimes if you don’t face it, it’s a way to say, ‘I don’t know about it. It does not exist.’ But it does exist. It exists with the exhibition, with showing Hadar’s portrait, with his uniform,” she said.

The Goldins have traveled to New York, Miami and Los Angeles, lobbying for the return of their son’s body.

The Goldins have traveled to New York, Miami and Los Angeles, lobbying for the return of their son’s body.

“We are looking for ways to raise it as an American issue. And by that, getting the support of the U.S. administration to motivate Hamas to bring Hadar home,” Leah said.

At the collection’s opening Feb 15 at the Museum of Tolerance, Rabbi Marvin Hier, founder of the Simon Wiesenthal Center and its Museum of Tolerance, delivered a sermon, referring to a passage from Exodus, where Moses made an oath to carry his ancestor’s bone into the Promised Land.

“We have the obligation to retrieve the bones of our lost brother like Moshe Rabbeinu,” his voice, a desperate plea, echoed through the microphone. “We must do everything we can.”

On Feb. 20, the collection moved from the Museum of Tolerance back to Israel, traveling, yet again, to the Knesset before going to the Opera Tower in Tel Aviv. The Goldins are asking the community for help.

“We’ll appreciate any advice and any help to resolve it and bring some closure to our case,” Leah said.

Plain and simple, they want to give their son a proper Jewish burial.

Who was Hadar Goldin? He was a son, a brother, a fiance, an intellectual, and an artist. He was a voracious reader, a fan of J.R.R. Tolkien, and an espresso drinker.

“I used to do still photography until Hadar took my camera when he was a teenager,” his mother said, “and then he was the one behind the camera.”

Hadar observed the world. Ever since he was a kid, he liked to draw and write. He was a doodler, illustrating scenes of daily life, jazz on a street, caricatures of people he knew. He’d draw in pocket notebooks, on scraps of paper, whatever he could find. On the back of an equipment list while stationed near Gaza, he drew his wedding invitation, a scene portraying his fiance and himself in a house, ripened pomegranates in the trees. He painted oil-on-canvas scenes of a man fishing; deer in a pasture; the war-torn skyline.

Hadar Goldin was 23 years old when he died, three weeks before his wedding.

There is a piece in the collection that hangs in Simcha’s study at home when it isn’t traveling with the exhibition.

“You need to see it,” Simcha said. “It’s a long debate whether it’s a bird or something else.”

It looks like a dove, hovering over a lake, its wings stretched out in full extension. An orange sun bleeds into the sky as a girl, doused in a powdery white light, watches from a distance.

“The sad thing is it’s only the potential. He was killed, so you can only see his potential on the walls. It’s very sad. It’s very painful,” Simcha said about his son’s artwork.

“But on the other hand, it’s there. It’s unique. It’s nice,” he said. “It’s fantastic.”

Correction: 3/1 – This story originally said Leah Goldin is a computer programmer – she is a doctor of computer science.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.