On a Sunday last December, Joe Wedner leaves a church service carrying fruit from a free food pantry. Photos by Eitan Arom

On a Sunday last December, Joe Wedner leaves a church service carrying fruit from a free food pantry. Photos by Eitan Arom For Joe Wedner, theology is well-worn territory. God and His workings are among the trains of thought that keep Joe’s mind chugging, often in a broad and frenzied circle. At the center of that theology is a paradox that causes Joe a fair amount of strife.

Joe is 77, stooped and bearded. He’s a Jew by birth, but in practice, at least since 2013, he honors every faith — Christianity, Islam, Judaism, Buddhism, etc. — without discrimination or distinction. His face betrays the weatherworn quality of someone who has spent years living on the streets, and he carries an air of all-consuming tragedy.

“I cry a lot — so I’m sorry — but I’ve never been locked up for crying,” he told me the first time we sat down together, in January 2016 at Native Foods Café, a vegan restaurant in Westwood.

He sat in front of a heaping pile of beans, grains and vegetables, his pushcart parked next to our table. Overflowing with pieces of cardboard and extra jackets, the cart held the sum of his worldly possessions.

Vegan cuisine was Joe’s idea. He avoids processed foods and animal products, not for ethical or health reasons, but religious ones. When a waiter stopped by our table, Joe pointed to his food and asked, “Is this the most natural, unchanged-from-God whole food that we got?”

God pervades Joe’s existence.

“There is no place that God is not,” he told me. “God is everyplace. God is in every belief. God is in every emotion.”

His relationship with the Almighty is perhaps Joe’s one remaining comfort in this world, although even that relationship is not without strain. According to Joe, two activities offer him any sort of solace from the unrelenting fear and anxiety that rule his day-to-day existence: religion and sex. Since Joe is homeless and elderly, it’s not easy for him to find sexual partners, so religion is all that remains in any practical sense. Every week, when he has the time, he attends as many religious and spiritual services as he can.

But his God, he insists, is not a particularly benevolent one. The paradox at the heart of Joe’s theology is that although God is everywhere, He is a maniac.

“God can do the impossible,” he explained to me. “He can give absolute, total freedom and still prevent man from sinning and leaving Him, and therefore He can prevent suffering. Why doesn’t He prevent suffering? Because He’s mentally ill. He’s seriously mentally ill, and we are His image and likeness, and we are mentally ill.”

When it comes to his own mental illness, Joe makes no secret. In his second email to me, shortly after we first met, he wrote, “I thought you might be interested in the attached information.” It was a psychiatric report diagnosing him with bipolar disorder, for which he refuses medication. He also admits to being delusional and cripplingly paranoid.

[To give or not to give? Experts weigh in]

For Joe, delusion bleeds freely into reality and vice versa. Consider his present life plan: Joe is taking UCLA Extension courses on the entertainment industry, hoping to land a high-paying job and strike it rich. The basis for his plan is his conviction that education is the key to income. Although that makes enough sense, his plan to strike it rich stretches credulity.

Yet Joe sticks to his plan doggedly, even if it means forgoing a roof over his head.

Joe has been homeless for four years, a condition that puts him in the category of “chronically homeless” — those homeless for a year or more due to debility. He is less an anomaly than a poster boy for the definition: By the latest count, 61 percent of the roughly 13,000 people who are chronically homeless in Los Angeles County are mentally ill, about 8,000 people total, according to the Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority.

If there is an anomaly to Joe, it’s his religious background.

In 2014, the Pew Research Center ranked Jews as the most financially successful religious group in America. Only 16 percent claimed a family income of less than $30,000 a year.

Tanya Tull, a homelessness policy pioneer and CEO of Partnering for Change, said in addition to Jews living on the street, many others eke out an existence in deplorable conditions in cramped apartments in poor neighborhoods like MacArthur Park and Mid-City. She cited as one example a 71-year-old retired Jewish man who spends more than 80 percent of his Social Security payments on rent in a studio apartment in Pico Union, where he experiences regular power outages and struggles to treat a chronic pulmonary condition.

Some local impoverished Jews are clients of The Jewish Federation of Greater Los Angeles and its partner organizations. Federation estimates that together, the groups help about 20,000 Jews living in poverty, providing them with free kosher meals and grant assistance for housing, paired with case management.

But that number reflects only those whom they help.

“There are more people out there — Joe is a perfect example — who are not accessing these services,” Lori Klein, Federation’s senior vice president for its Caring for Jews in Need program, told the Journal.

Federation estimated that 50,000 Jews lived in poverty in Los Angeles in 2014, the latest year for which data are available. More than 600,000 Jews live in the Greater Los Angeles area.

Klein suggested that Joe call a central access hotline of Jewish Family Service of Los Angeles, which directs people experiencing financial instability to appropriate resources.

Joe said he called in April, but found that the services it offered were more or less the same as those he already was getting from a Kaiser Permanente social worker. As for housing, Joe, it turns out, has other priorities.

I first met Joe when I showed up for an assignment at jumu’ah, the Muslim prayer service offered Friday evenings at UCLA. I was early and found Joe sitting on a metal folding chair in the hallway outside the prayer room with the demeanor of someone who didn’t have anywhere else to be.

After services, I took down his email address. Joe checks his email frequently — somewhere among the loose cardboard and plastic bags in his cart was a laptop that he’d had since 2013. (It’s since been stolen; he now returns emails via public computers at UCLA.)

It turns out that Joe has little to hide and, by his estimation, much to gain from an interview.

“The more you tell the better,” he told me at Native Foods. “My psychiatrist does not disagree that my whole problem is a girlfriend deficiency, and I’m trying to get that out there.”

It was only much later in the interview that I learned he has a wife and daughter — but that hasn’t interrupted his other plans. Joe is interested in obeying all of God’s commandments, including to “be fruitful and multiply.”

“I need a lot of girlfriends,” he said, without a hint of irony or jest. “So I want to put that out there, just in case there might be somebody like me, that also wants a lot of children, a female. Because … I’m a panhandler, and a panhandler knows if you say the same thing to enough people, no matter what it is you’re saying, if you say it to enough people, you find a few, one or a few, that’ll agree with you.”

With Joe, it’s sometimes hard to distinguish between delusion and what could be described merely as misplaced priorities. His desire to have children is motivated not just by the joy of sex but also by the conviction that children represent “eternal life and salvation from death.” But whether Joe should father a child at 77, with no means to support one, is a consideration he ignores. He remains enthusiastic in pursuing his goal.

In the middle of the conversation, a young woman approached our table to express interest in the interview. Joe’s demeanor changed instantly. His eyes lit up, and he began talking more quickly, almost frantically. It occurred to me that he was putting on a show.

“You could sit down,” he told the young woman. “You could sit down and listen to me. If you’ve gotta go — want my email address? I’m an extremely interesting person. You’ll never find anybody running around loose more mentally ill than me.”

Joseph Leo Wedner was born on Feb. 2, 1940, in Detroit.

His father was born to an Orthodox family near Sanok, Poland. His mother, an American, was what Joe called a “three-day Jew,” someone who attended synagogue approximately three days a year. They had one other son, John, since deceased.

At 13, Joe became a bar mitzvah at Congregation Shaarey Zedek, a Conservative synagogue near Detroit. He recalls his trips to his father’s shul with fondness if also with a bit of detachment, saying, “That was very nice, people talking with their creator, praying and asking to not get sick with colds or anything else.”

But even at a young age, Judaism didn’t quite do it for him. He remembers, as a 5-year-old, being beset with a paralyzing fear that his faith couldn’t extinguish. He recalled his envy when he saw a glow-in-the-dark crucifix hanging over the bed of a grade-school friend.

“I thought, ‘Man, oh, man, everybody’s lucky except me. I gotta have horrible, terrible nightmares ’cause I’m scared of school. Why can’t I go to Catholic school and have that crucifix hanging by my bed?’ ” he said.

His family life was dysfunctional, he said: “That’s what our family does, is yell at one another. Big ones yell at the little ones.”

But Joe managed to hold things together and graduate from a local college, enrolling in medical school at the University of Michigan. Soon, though, his mental health began to slip, as it would at crucial moments in his future. He described struggling with paranoia so severe that he didn’t think he could make it in medical school. When things got bad, he went to see the dean.

“I told him, ‘I’m going to flunk out anyway, I’ll never get through this, it’s too hard, and I’m afraid of the American Nazi party. I’m going to Israel,’ ” he recalled.

His experience in Habonim Labor Zionist Youth as a teen in Detroit had convinced him that a Jew could live happily only in a socially just environment in Israel. So in January 1964, he left for Israel, landing at Kibbutz Sarid in Israel’s north.

It didn’t quite play out the way he had hoped. Instead of working, he “slept and ate all day and chased the tourist girls,” he said. He was kicked out, and he fell in with some hippies — or maybe they were secret police. Joe can’t be sure.

His new friends taught him to play guitar and beg on the street. After a stint in Abu Kabir Prison in Tel Aviv on narcotics charges — “all the hippies were doing narcotics,” he said — he felt disillusioned and left the country the year after he arrived.

From there, Joe tramped through Europe and the Middle East, his first experience with vagrancy. But, in 1968, he was back in the United States, and over much of the next four decades earned a living wage subsisting on odd jobs and help from his mother as he moved from place to place, with stints in New York, California, Washington state and Hawaii. Things weren’t always great, but there was a roof over his head. And then came Josie.

It was 2004. Joe had been living in the Philippines for about a year, living off the interest from an inheritance from his mother, when his psychiatrist suggested he hire a live-in maid because he hadn’t cleaned his Manila apartment in more than a year.

Josie showed up at his door. “Right from the beginning, we fell in love,” he said.

They were married a short while later. Their daughter was born in 2006, and a year later, they moved to Loma Linda in San Bernardino County, where they lived in a “very small, but very comfortable apartment.” The marriage was a rocky one, which he blames on his own upbringing.

“My family is dysfunctional, extremely, is as dysfunctional as a family can be without actually flying apart,” he said. “It was always screaming, weeping, crying, insulting, criticizing etc., so I did that to my wife, whose family never did that.”

In 2011, they traveled to Josie’s hometown, Zamboanga City, in the Philippines, moving from apartment to apartment. Josie started a few businesses, but they all failed. By 2013, he recalls, she told him, “Get me back in the USA, I don’t like it here.” He flew to Los Angeles, with plans for her to follow later — but no plan of where to stay once he left the airport.

Even living on the street, Joe was sending money back to Josie from his Supplemental Security Income, a federal program for the elderly, blind and disabled. After a while, he couldn’t afford to continue. “I heard from her when she needed money and then, when I stopped sending her money, I haven’t heard from her,” Joe said. She last contacted him in December. I reached out to Josie through email and Facebook, but she did not respond.

Nonetheless, Joe is keen to bring his wife to the U.S. While his strategy may be a doubtful one, he persists: To earn a visa for Josie, he needs to demonstrate to Immigration and Customs Enforcement that he can support her. Thus, his coursework at UCLA.

Sevgi Cacina, a film student at UCLA Extension who is making a documentary about Joe, first approached him after she saw him pitch his skills as an actor and producer at networking events. The crowd typically doesn’t know what to make of Joe, but one thing is certain, she said: “He’s not joking.”

He’s even enlisted some help. Screenwriter Brooks Elms said Joe enrolled in an online course that Elms taught through UCLA Extension in 2015, during which Joe diligently completed each assignment. After the course concluded, the students invited Elms to lunch in Westwood.

“Joe came to that lunch, rolled his cart right there from the street, and asked how he could get a movie made,” Elms wrote in an email. “I asked why he was even spending money on a film class when he could be spending it on basic survival needs, and he was determined to learn about the film business and make something happen that way.”

Elms said he’s now helping Joe make a film about Joe’s life on the streets.

“We plan [to] post it online with hopes it will bring him some much-needed income,” Elms wrote.

Until that happens, Joe remains on the street and sleeps in a sleeping bag in Westwood. Mostly, he’s tenacious about his plan, but sometimes his resolve lapses.

“This is as close to work as I got, giving an interview for a lunch,” he said at the vegan joint, “which is extremely disconcerting to me, because now I’m afraid I’ll never get my wife and daughter back.”

Joe’s separation from his wife and daughter is “an overwhelming tragedy that pervades my being every moment. … It causes anxiety, depression and every bad feeling.” Any kind of spiritual activity, from Mass to a 12-step meeting, relieves the pain of those feelings.

One day, on a visit to the Seventh-day Adventist church in Santa Monica — which he calls “Simcha Monica” — he ran into a Chabad missionary near the church.

As a lapsed Jew with a spotty relationship to the tribe, he was nervous about allowing the rabbi to lay tefillin on him. So he thought about it, and prayed about it, and decided he’d better drop by a Chabad.

“If I’m striving for God to help me, in everything, then I got no better or worse chance at the Chabad Lubavitch synagogue than I got anyplace else, so I’ll go,” he said. “So I started going. The more I went, the more I started feeling that … if I know what’s good for me, I better add Roman Catholic and Muslim to the places I pray.”

Joe’s schedule for religious services is noncommittal and wide-ranging, though it leans Christian. Perhaps his favorite place to pray is a Christian congregation called the Basileia Community, which meets in a Baptist church in Hollywood. At one point, he was going twice a week, on Tuesdays and Sundays, while attending Roman Catholic services on Mondays and Thursdays and Chabad or Seventh-day Adventist services on Saturdays.

Lately, school has interfered with his attendance, and he’s often forced to stay around UCLA for services. One Sunday in December, I agreed to drive him to Basileia. We met on the corner of Westwood Boulevard and Le Conte Avenue with boisterous crowds of students surging by. He looked even smaller than I remembered, dressed in two coats and too-long pants that he’d rolled up at the cuff over a scuffed pair of brown loafers.

I loaded his pushcart, with its one broken wheel, into my car, and we set off for church.

On the way, I decided to raise the issue of permanent supportive housing — apartments made available by the city and county expressly for chronically homeless and mentally ill individuals like Joe. Los Angeles voters recently passed Measure HHH, a $1.2 billion bond that earmarks most of the funds precisely for building this type of housing. Joe conceded that it would be nice to have a toilet of his own, and the privacy to have company.

But “it might not be around here,” he speculated as we turned onto Wilshire Boulevard. “Then I’d have to wait for a bus and ride the bus and wait for a bus back … then it would slow down my saving up that $60,000 I need to show to get my wife over here.”

By now his foot was tapping violently enough to shake the car. The topic clearly made him anxious.

His thoughts are scattered, with a tendency to trail off or pivot wildly. On occasion, an unrelated question will reveal a heretofore-unexplored saga in Joe’s life.

By the time we reached Basileia, a question about his wife inadvertently had revealed details of the money he had inherited from his mother: Between 1984 and 2007, he said, he played the stock market, growing $250,000 into more than $800,000 at one point and living off the interest. When the market crashed 10 years ago, Joe said his bank account flat-lined.

As we walked into the church, people were schmoozing around a light buffet. Joe wasted no time in loading up a plate with fruit and breakfast rolls. It had been some time since he had been here, and several people approached him to say hello. A massive man with a kind face and a blond bun, the drummer in the congregation’s music ensemble, greeted Joe with a fist-bump.

Explaining my presence there as a Jewish Journal reporter, I mentioned that Joe was Jewish.

“I didn’t know you were Jewish, Joe!” a fellow churchgoer interjected.

I was mortified for outing him, but Joe was unfazed.

“I’m all things,” he explained.

For Joe, God is in every religion, all beliefs, indiscriminately and without exception. He likes Basileia for its inclusiveness and the kindness of his members. But it has no monopoly on his faith.

The band started to play and the hymns began to flow. “Holy Spirit, come fill this place!” the congregants sang, sitting in a semicircle under the exposed rafters of the tall, gabled roof.

The gathering was a dressed-down affair, community-oriented and progressive. The room flickered softly with the glow of candles and Christmas lights, and a plain, wooden cross overlooked the scene.

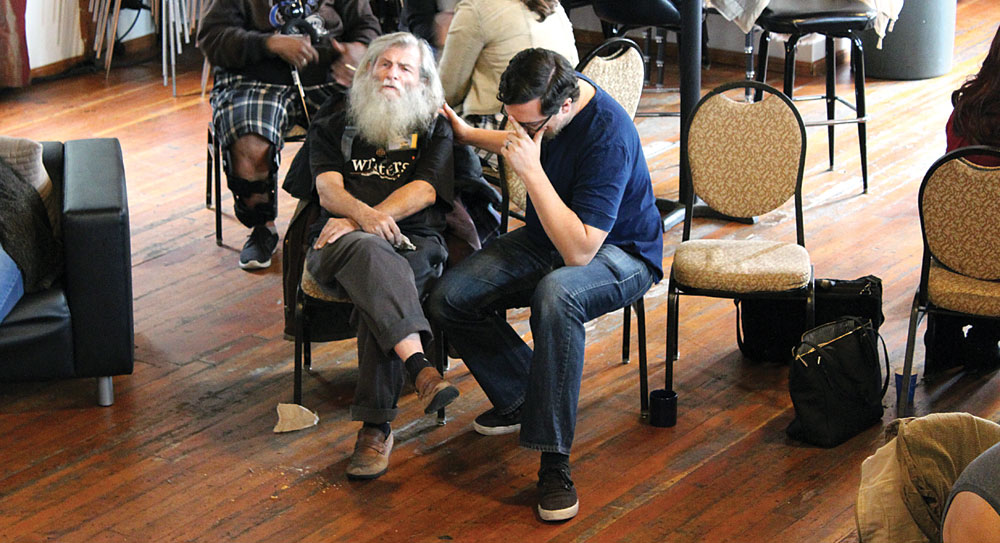

While the music played, Joe crossed his legs and tilted his head downward, staring just past his interlaced fingers, his white beard fanning out over his UCLA Extension T-shirt. The pastor, Suz Born, a bespectacled woman with a soft voice and the measured demeanor of a kindergarten teacher, kneeled next to him with her hands raised in the air.

Soon, the music slowed to three or four chords repeated on an acoustic guitar. The frenzied foot tapping that had shaken my car had slowed to a soft, irregular beat.

When the service broke up, he stuck around to chat with friends and acquaintances, indulging them in detailed explanations of his theology. “The only reasonable conclusion is that God is mentally ill,” I overheard him saying.

He shares his theory widely, even if to awkward laughs or kind dismissals. It doesn’t earn him many friends. The Roman Catholics and Seventh-day Adventists say he’s blaspheming God. He says they’re blaspheming God by calling his truth blasphemy, since truth is God.

After services ended, church elder Bill Horst sat beside Joe to pray with him, resting his head on his hand and concentrating intensely. Later, Horst told me he prays for Joe to experience the mental soundness that often eludes him and to find a way off the streets.

Horst said that despite “packaging that’s a little tricky to get past,” Joe gets along OK at Basileia. At one point, he was making sexual overtures to single women there in a way that made them uncomfortable, Horst said — but church leaders sat him down and asked him to respect certain boundaries, and to his credit, he did.

“Someone can have a meaningful relationship with someone like Joe even if they find that difficult to imagine,” Horst told me on the phone later. “There is something real and coherent and worthwhile there if you’re willing to look for it.”

As people began to file out of the church, Joe headed to a basement room to pick up some donated food. He made a beeline for the fruits and vegetables. “There’s salad over here, boyfriend,” a homeless woman called out to him. But the salads were of the prepacked grocery store variety, and some had meat in them, so he passed over them. Even with his dietary restrictions, food is the least of his worries. Between panhandling and food banks, he has plenty. If he lacks for something, it’s not provisions but companionship.

“I need friends,” he said at Basileia. “My family is gone, so I need friends. Inshallah” — if God wills it.

Joe’s first serious brush with Christianity came during a lockup in Washington State Penitentiary in January 1978, when he was 37. He’d enrolled in a university-level accounting course in Tacoma, Wash., hoping it would set him on a path to quick riches. But he was failing and frustrated. One day, he decided somebody was driving too fast down his street, so he took out a loaded .45-caliber semiautomatic handgun and brandished it, yelling, on his porch. He was imprisoned for 25 months before his mother, an attorney, managed to get his sentence vacated on a technicality.

Prison was not a welcoming place. “The guards were unfriendly and the prisoners were even more unfriendly,” he said.

The only people who would speak with him were the missionaries.

“The Christian missionaries were there every day. I saw Jewish missionaries there once the whole 25 months I was there,” he said. “So naturally, I read the Christian Bible — a few times.”

He acquainted himself well with the text and continues to read and reread it. He keeps one in his pushcart. These days, one of Joe’s favorite verses to quote is the Man of Sorrows in Isaiah 53: “He was despised and rejected by men, a man of sorrows and acquainted with grief; and as one from whom men hide their faces he was despised, and we esteemed him not.”

It’s not hard to puzzle out why he’s so fond of the verse. On the one hand, it’s easy to imagine Joe as Isaiah’s outcast, “pierced for our transgressions … crushed for our iniquities.”

On the other hand, it’s a potent illustration of a capricious and unsparing God, doling out suffering: Why would any but a mentally ill God cause one man to suffer for all the rest?

And so, my question for Joe was, why go to such great lengths to worship a God he believes — fervently — to be insane? Joe’s theology and his delusions often are baroque, but they’re pieced together from pieces of simple, direct logic. To my spiritual question came a pragmatic answer.

On weeks he goes to prayer services and reads from the Bible, he said, “things coincidentally or not coincidentally go better. And so I just keep doing it.”

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.