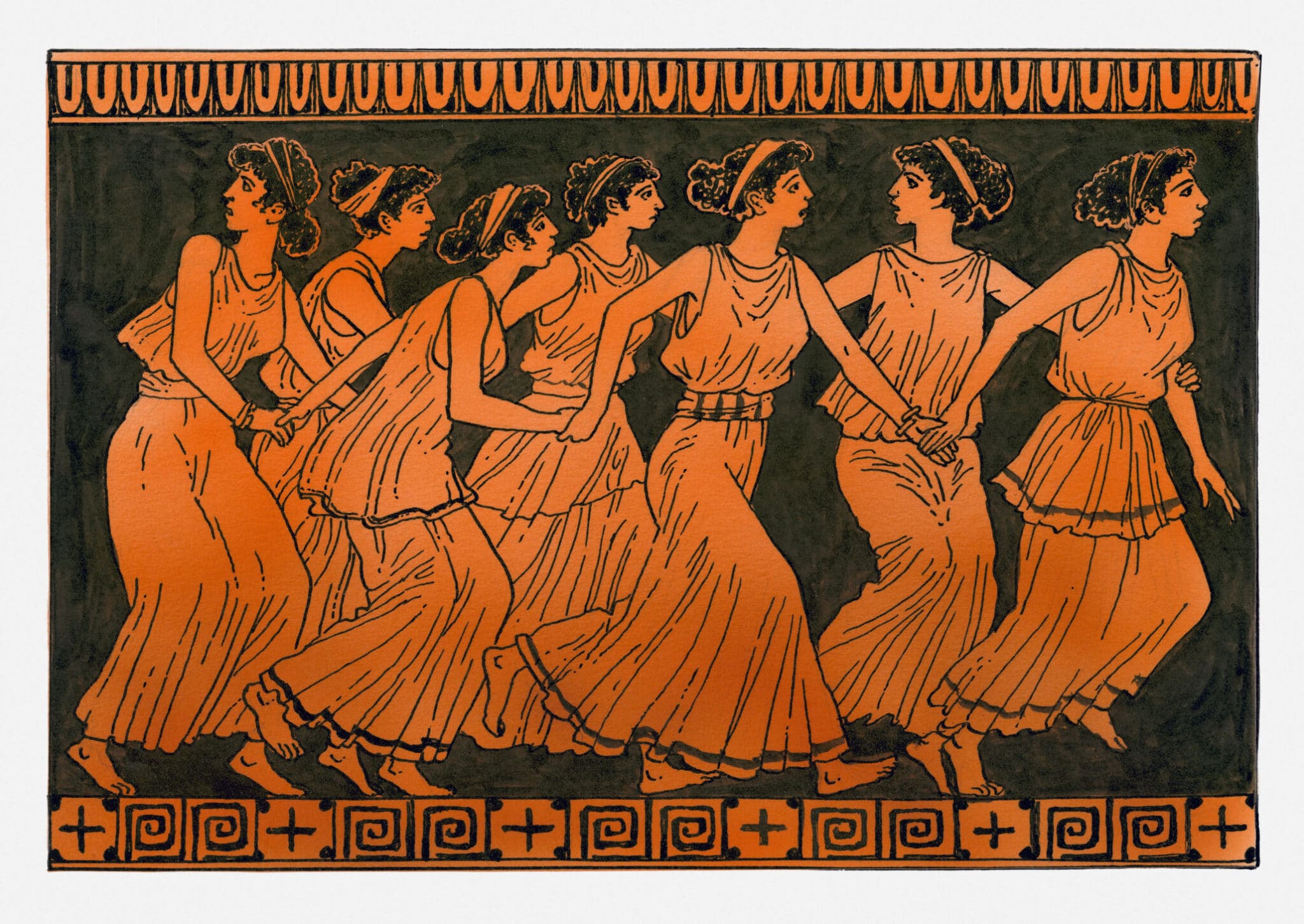

Dorling Kindersley/Getty Images

Dorling Kindersley/Getty Images We do not learn our language by transcribing every word like monks

into our manuscripted brain,

we learn it in the collocations that are lexically learned chunks.

That’s why we do not say “strong rain,”

but “heavy rain,” and on the other hand will only say “strong tea” —

tea’s never “powerful.” We learn

to speak in chunky phrases that we use while we’re poetically

inclined, when talking of an urn,

to think of “Grecian urns” and Keats, and when we talk of mom and dad

think, Larking, that they “f’d us up.”

Since speech is chunky we become mere walking platitudes. How sad!

Speech runneth over like a cup,

overflowing sometimes in a style some linguists label “feminine,”

the language that weak people speak

condoning with conditions typically used by women in

a style that has been labeled “weak.”

The Torah’s Israelites use language that is weak on two occasions,

addressing as if they weren’t masc-

uline both God and Moses, asking to be treated with the sort of patience

that’s typically a woman’s task.

Echoing J. L. Austin, the gender of two “utterances” in the Bible influences their performance

to make them “utterances of weakness,” grammatically behaving just like female hormones.

In “Women Know Exactly What They’re Doing When They Use ‘Weak Language,’” NYT, 7/31/23, Adam Grant, an organizational psychologist at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School, writes:

It turns out that women who use weak language when they ask for raises are more likely to get them…. In 29 studies, women in a variety of situations had a tendency to use more “tentative language” than men. But that language doesn’t reflect a lack of assertiveness or conviction. Rather, it’s a way to convey interpersonal sensitivity — interest in other people’s perspectives — and that’s why it’s powerful.

The Torah twice uses feminized “weak language” in its descriptions of negotiations. In Num 15:11 Moses address God as את, which is the feminine word for “you” when pleading to God for his survival:

טו וְאִם-כָּכָה אַתְּ-עֹשֶׂה לִּי, הָרְגֵנִי נָא הָרֹג–אִם-מָצָאתִי חֵן, בְּעֵינֶיךָ; וְאַל-אֶרְאֶה, בְּרָעָתִי. {פ} 15 And if Thou deal thus with me, kill me, I pray Thee, out of hand, if I have found favour in Thy sight; and let me not look upon my wretchedness.’ {P}

The Israelites use the feminine את when pleading to Moses to enable them to survive during the Sinai theophany by acting as God’s spokesman, so that they will not die when hearing God’s voice:

כג קְרַב אַתָּה וּשְׁמָע, אֵת כָּל-אֲשֶׁר יֹאמַר יְהוָה אֱלֹהֵינוּ; וְאַתְּ תְּדַבֵּר אֵלֵינוּ, אֵת כָּל-אֲשֶׁר יְדַבֵּר יְהוָה אֱלֹהֵינוּ אֵלֶיךָ–וְשָׁמַעְנוּ וְעָשִׂינוּ. 23 Go thou near, and hear all that the LORD our God may say; and thou shalt speak unto us all that the LORD our God may speak unto thee; and we will hear it and do it.’

These two verses are—please pardon my bilingually bisexual pun— “utterances” that reflect what J. L. Austin might have called “performances of weakness.” In “How to do things with wars: The life of the philosopher who ‘changed the whole idea of what language is,” TLS, 8/4/23, Lonon School of Philosophy’s Jane O’Grady writes:

Yet, as Austin insisted, “when we examine what we should say when, what words we should use in what situations, we are looking not merely at words (or ‘meanings’, whatever they may be) but also at the realities we use the words to talk about”. And, he argued, the way we use words in fact changes reality. “When I say ‘I name this ship the Queen Elizabeth’ I do not describe the christening ceremony, I actually perform the christening”, he wrote; “and when I say ‘I do’ (take this woman to be my lawful wedded wife), I am not reporting on a marriage, I am indulging in it”. I am, in fact, “doing something rather than merely saying something”. Although it resembles an ordinary factual statement, what Austin called “a performative utterance” cannot be either true or false – it acts on, and alters, the social world. Yet so too, he argued, do many avowedly descriptive statements. The sentence “your car is damaged”, for instance, has a literal meaning, but it may also be, to adopt Austin’s terminology, an “illocutionary act” (a warning) and perhaps has the “perlocutionary” force of alarming the person who is warned…..

But just as his war work had significantly, if indirectly, executed military and defensive activities, so he was not merely investigating concepts such as “action”, but revealing that language is itself a form of doing – and he thereby changed the whole idea of what language is. Austin’s “speech act” theory, elaborated by his student John Searle and others, has also extended into postmodern territory, such as Judith Butler’s claim that to be male or female is less a matter of biology than of performance.

Rabbi Wolpe commented, citing Aaron’s prayer that God should cure his sister Miriam:

El nah r’fah nah lah is also weak, I’d say, with two pleases in five words.

Rabbi Wolpe implied that Moses’ “speech act” in which he rephrased Aaron’s prayer to God was a forceful five-phrased feminine performance. Num. 12:13 states:

יג וַיִּצְעַק מֹשֶׁה, אֶל-ה לֵאמֹר: אֵל, נָא רְפָא נָא לָהּ. {פ} 13 And Moses cried unto the LORD, saying: ‘ El nah r’fah nah lah. Heal her now, O God, I beseech Thee.’

Echoing J. L. Austin and Rabbi Wolpe, I suggest that Moses was speaking like the nursing father — which he had told God he did not wish to be — saying in Num. 11:12:

יב הֶאָנֹכִי הָרִיתִי, אֵת כָּל-הָעָם הַזֶּה–אִם-אָנֹכִי, יְלִדְתִּיהוּ: כִּי-תֹאמַר אֵלַי שָׂאֵהוּ בְחֵיקֶךָ, כַּאֲשֶׁר יִשָּׂא הָאֹמֵן אֶת-הַיֹּנֵק, עַל הָאֲדָמָה, אֲשֶׁר נִשְׁבַּעְתָּ לַאֲבֹתָיו. 12 Have I conceived all this people? have I brought them forth, that Thou shouldest say unto me: Carry them in thy bosom, as a nursing-father carrieth the sucking child, unto the land which Thou didst swear unto their fathers?

Gershon Hepner is a poet who has written over 25,000 poems on subjects ranging from music to literature, politics to Torah. He grew up in England and moved to Los Angeles in 1976. Using his varied interests and experiences, he has authored dozens of papers in medical and academic journals, and authored “Legal Friction: Law, Narrative, and Identity Politics in Biblical Israel.” He can be reached at gershonhepner@gmail.com.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.