Benny Gantz, former Minister of Defense and part of the emergency government, attends the funeral for First Sergeant Major Gal Meir Eisenkot, 25 years old, at the Herzliya cemetery on December 8, 2023 in Herzliya, Israel.

(Photo by Alexi J. Rosenfeld/Getty Images)

Benny Gantz, former Minister of Defense and part of the emergency government, attends the funeral for First Sergeant Major Gal Meir Eisenkot, 25 years old, at the Herzliya cemetery on December 8, 2023 in Herzliya, Israel.

(Photo by Alexi J. Rosenfeld/Getty Images) The least secretive secret of Israel’s war is politics. Ask a politician, right or left, and get a generic answer: When the war ends, we will turn to politics. Why are they saying such things – why are they, well, not telling the truth? Because this is what the public expects them to do. Or, to be more accurate: the public expects them to forgo all political considerations and machinations until the war is over, but since such hope is unrealistic (politicians always – always – think about politics), the next best thing is to pretend: Play politics – without admitting to do it. And when asked about it, by a nagging journalist or a political rival, deny it with manufactured fury and claim that the mere questioning about politics is the problem – that’s the real disruption!

They all do. Some of them more than others, some with less style than others. This week, the finance minister mounted a battle aimed at providing one of his party’s ministers the funds necessary for supporting settlement activity. He argued that the funds are necessary, essential, for the protection of the settlers. That might be true for some of it, and yet, the funds slated for the defense of Israelis are normally handled by the Defense Ministry – what the finance minister is insisting on is the extra funds that are handed out by a ministry whose mission is not defense, it is support for political allies.

All parties are buzzing with political activity and with rumors about this or that leader and what they intend to do after the war.

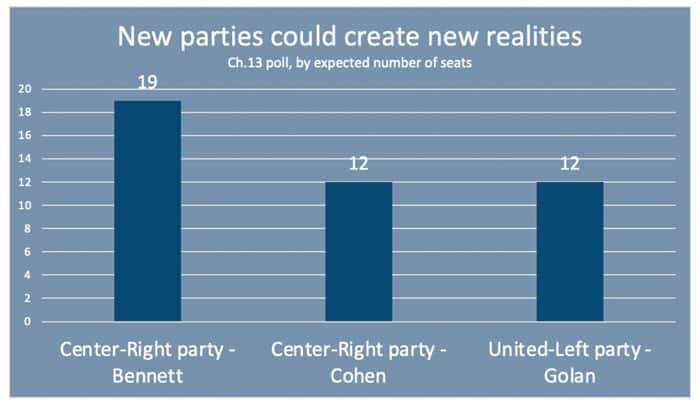

He is not alone. All parties are buzzing with political activity and with rumors about this or that leader and what they intend to do after the war. The polls are already examining various scenarios: what happens if former PM Naftali Bennett reenters the fray (as everyone expects him to do). What happens when former head of Mossad Yossi Cohen enters the fray (same expectation). What happens if they join current parties (Bennett with Gantz – Cohen with Likud), what happens if they form their own parties, separately or jointly. And what will Gideon Saar do: He is currently a minister and a member of the Mamlachti party (Gantz), but he seems to search for a way out – possibly back to Likud. The first sign of such a move will be his decision to stick with the coalition when the other Mamlachti ministers, who joined the government for the war, decide its time for them to leave.

In the meantime, the leader of the Labor party announced her decision to retire. So, the left is reanimated by the prospect of renewal, probably a merge of Labor and Meretz, possibly headed by former General Yair Golan, a hero of Oct. 7th (he acted courageously to rescue civilians from the killing fields). A party headed by him is expected to get a hefty number of seats. What can he do with those seats, that another question. That’s the important question. Because the day after – at least, this is what the current polls tell us – is a new day. The current coalition of right-wing/religious parties will not be able to reemerge as a ruling coalition. A different political landscape would open new options: A centrist coalition (from Likud to Yesh Atid), a Zionist coalition (no Haredis and Arabs), a center-left coalition supported by the Haredi parties, who knows what.

But that’s the real question. That’s the real question for us Israelis who aren’t running for office and therefore are less concerned with personal ambitions and more with the nature of policy and politics on the day after. The personal fate of Yossi Cohen, or Bennett or Sa’ar or Golan is of little interest – but these people are going to have the power to reshape Israeli politics, to set its priorities, to dictate a new tone for public discourse, to design a functioning coalition, to tackle Israel’s challenges. Oh, and there’s Netanyahu … lest we forget. The public expects his removal, but he might have other plans, and still has staunch supporters who could help him do whatever it is that he plans to do.

Deciding what challenges must be dealt with, and in what sequence, and how – that would be the most pressing and difficult mission of the next coalition when it emerges, possibly after a new election. Most Israelis believe that having new leadership when the war is over is essential. The coalition might want to avoid an election, because it is not in good shape to win that round, but it’s hard to see how any coalition could pull off such a maneuver after the shocking events that it is going through. Ask politicians in public and they’ll tell you they don’t think about politics. Ask them in private and they’ll say that they expect Israel to have a new election between April and October of 2024.

Something I wrote in Hebrew

Merav Michaeli, the head of the Labor party, is on her way out. Here’s what I wrote when she announced her decision to quit:

Michaeli is not Yitzhak Rabin, nor Shimon Peres, nor Isaac Herzog. She is not made of the material of which leaders of significant parties are made of. Her announcement … is a kind of admission of this. Michaeli recognizes that she will not be able to lead the party, and there are doubts there will even be a party left to lead. Maybe … if it reunites with Meretz, it can maintain some semblance of revival. But a real revival is currently not in sight. It might have been better to just close it down. The slow dying of such a party is a nuisance to the political camp of which it is a part.

A week’s numbers

Political scenarios force Israelis into thinking about their preferences and priorities. Here’s one survey that asked about three possible new parties:

A reader’s response:

Eva Rosenfeld asks: “When will Israeli ‘refugees’ go back to their homes?” Answer: When it’s safe and, in some cases, rebuilt. Of course, the later part of the answer is the easier to define.

Shmuel Rosner is senior political editor. For more analysis of Israeli and international politics, visit Rosner’s Domain at jewishjournal.com/rosnersdomain.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.