Lior Mizrahi/Getty Images

Lior Mizrahi/Getty Images The “Basic Law: Torah Study” proposal caused an uproar for no more than a day. Too bad. It is better to dwell on it for a few more days. Because this is a proposal that obliges Israelis to take a fresh look at the Zionist vision and ask where it is headed.

The ultra-Orthodox United Torah Judaism Party (UTJ) submitted the proposal about a week and a half ago. The first clause of the bill says: “Torah study is a supreme value in the heritage of the Jewish people.” Can you disagree with such statement? The proposed law then continues: “Those who take it upon themselves to devote themselves to learning Torah … will be considered to be serving a significant service to the State of Israel and the Jewish people.”

The text and the bill can be considered a tactical statement. But I think it is more appropriate to treat them as an essential position. As a challenge.

When the bill was presented to the public, the uproar forced the government to clarify that it does not intend to pass such legislation. Why uproar? the public outcry mostly concerned two tactical questions. The first, a truly boring one, is the question of timing. The bill was presented merely a day after the dramatic climax of the judicial reform crisis, when the Knesset canceled the ability of the court to use Probable Cause as a tool of judicial review of government actions. So the timing was really poor. MK Matan Kahana wrote: “My ultra-Orthodox brothers, do you really think that yesterday was the right day [for presenting such a bill]?”

The second tactical question concerns not the timing but the purpose of the proposed Basic Law. MK Gadi Eisenkot, former chief of the IDF, called it a “recruitment bypass law.” This approach focuses on what the law was intended to do in the practical arena: To sabotage any future attempt at drafting yeshiva students to military service.

When the proposal is treated either as a timing error or as a policy tool, rather than as a principled statement, an important discussion is missed.

What is the important discussion that Israel ought to have at some point? It is about the question of whether studying Torah is the realization of a private desire or a state mission. Is the yeshiva student just a guy with a certain desire for a certain topic, or maybe he is my emissary, and all other Israelis’ emissary?

The ultra-Orthodox leaders who proposed this legislation clearly have pragmatic goals in mind, but they also have a strong principled case: they’d argue that for many generations, Torah sages were the people who realized what was perceived as the central vocation of the Jewish people. As the Mishna says: “The study of Torah is equal to them all.” Namely, to all other things.

Zionism substituted the ideal of the study of Torah with the ideal of national action. The mythological Zionists are the statesman Benjamin Ze’ev Herzl, the strategist David Ben-Gurion, the pioneer Yosef Trumpeldor, the underground leader Menachem Begin. Of course, Zionism also produced poets and thinkers, but most of these created in the service of the new vocation. Their outlook on youngsters busying themselves with the study of Torah in dark rooms was one of nostalgia and pity.

Secular Zionism abandoned the study of Torah almost entirely in exchange for realization of a pragmatic vision; Religious Zionism preserved Torah study, alongside a realization of a similar pragmatic vision. Both Zionist visions are challenged by the ultra-Orthodox. They never adopted the Zionist vocation. Their leaders hold a compass pointing to a different destination, and to their credit, they don’t lose sight of their preferred goals.

These goals are worth talking about because they pose a challenge to the Zionist majority. A large majority of Israelis identify the action in the service of the national project — military service first and foremost – as an expression of modern, relevant Jewish identity. Serving in the IDF is not a just formal civil duty — it is not like paying taxes or driving at the speed limit. It is a duty that has been given the status of sanctity. When Israelis are asked what being a good Jew entails, many of them would say that serving in the IDF is a clear manifestation of being a good Jew – much more say this about serving in the IDF than about studying Torah.

As Israelis brace themselves for a debate about the draft, they ought to come up with a substantial response to the Haredi challenge: To re-reason why in Israel a national service is indeed more sacred than the ultimate ideal of Torah study.

Basic law: Torah Study seeks to eradicate the distinct sanctity of mandatory national service. It seeks to place a competing value alongside mandatory national service. It essentially says: Trumpeldor, the Galilee pioneer, and Moishleh, the Jerusalem Yeshiva Bocher, have equal status. It’d be a shame to dismiss such bold challenge using tactical arguments. No – as Israelis brace themselves for a debate about the draft (expected in the winter term of the Knesset), they ought to come up with a substantial response to the Haredi challenge: To re-reason why in Israel a national service is indeed more sacred than the ultimate ideal of Torah study.

Something I wrote in Hebrew

Writing about the Israelis who informed the IDF that they no longer wish to volunteer for reserve service because of the judicial reform, I explained that in some countries, cruel dictatorships, the moral choice is easy, but in Israel, it is much tougher as every person must determine for themselves whether the current situation justifies such dramatic response:

“The dilemma of reservists in Israel, of doctors in Israel, of businessmen in Israel, of concerned citizens in Israel, is a dilemma that has no answer. When will all of them know and how will all of them know if it is indeed time to sabotage the goals to which the government of their country is striving?”

A week’s numbers

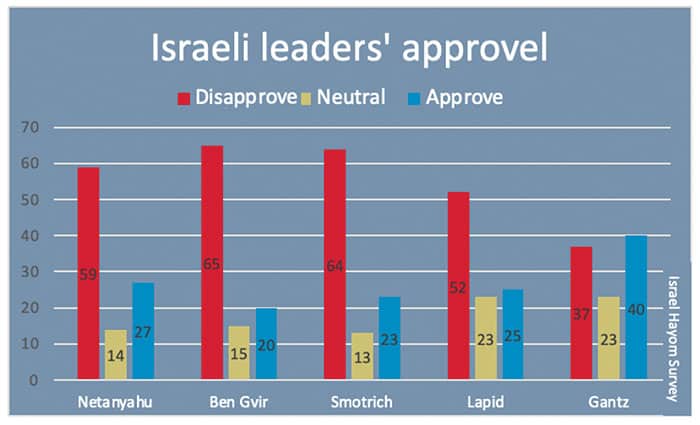

Partisanship means that very few leaders are acceptable to both sides and get a high approval rating. And yet, there is something to learn from these numbers:

A reader’s response:

David Mosk asks: “Do you think an agreement with the Saudis is likely?”

My response: Their current terms for a deal seem too costly, but maybe it’s a bargaining position. In such case, the answer is yes.

Shmuel Rosner is senior political editor. For more analysis of Israeli and international politics, visit Rosner’s Domain at jewishjournal.com/rosnersdomain.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.