If you were biting your nails over Israel’s political crisis in the last couple of days, you were wasting your time. This was a fake crisis. The involved parties, the ruling Likud Party and the inconsolable United Torah Judaism (UTJ) party, have no interest in dismantling a coalition that works for the benefit of both. Sure enough, three-four days later, the crisis is over. The parties agreed to keep the status quo on matters of religion and state.

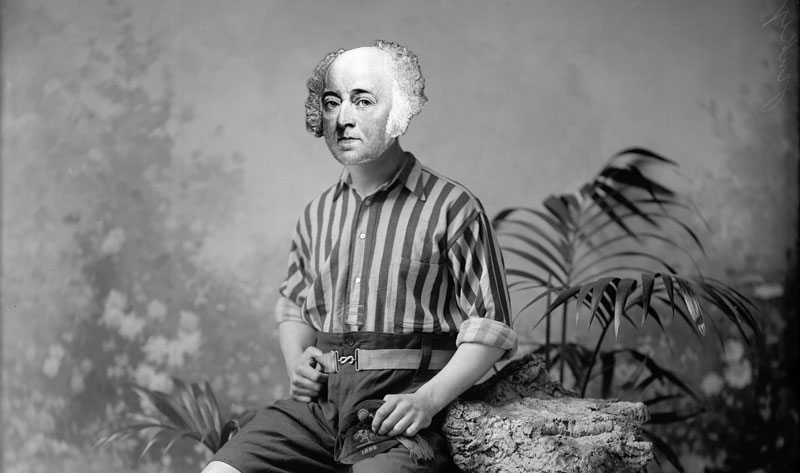

But one element of this short-lived crisis will not be undone: The decision by Health Minister Yaakov Litzman to resign. In fact, that is its most intriguing feature, the one worthy of attention. With the crisis over you would have expected him to come back, but he will not. Not until — and if — the Knesset passes new legislation that enables him to run his office as deputy minister rather than as minister.

What’s the difference? Well, there is a difference. The Haredi Ashkenazi party made it a symbolic feature of its participation in Israel’s political life to show its rejection of Zionist theology. The Haredis do participate; they do enjoy the benefits of having a voice, political power and even a role in running the government. But full membership as ministers in the cabinet is too much. So the compromise was a make-believe half membership: The deputy minister — in this case Litzman — can do whatever he pleases as if he were a minister. But the title of minister, and the official responsibility that comes with it, he will not have.

All this worked for many years, until the Supreme Court decided to put an end to it two years ago. The court forced Litzman to become a minister or relinquish his ministerial practice, and Litzman accepted the ruling and was appointed a minister.

There is no doubt that the court was right on principle in making that decision. There is no doubt that UTJ’s policy — get the power, reject the state that gives you the power — is annoying and hypocritical. Still, observers suspected that the court’s ruling will ultimately prove to be a bridge too far: It’s interventionist nature — its purist insistence on principle even though there was no practical downside to the arrangement — did not sit well with a pragmatic political system. The politicians want quiet and stability, and do they not see a need to fix something that is not broken.

These critics will not have their opportunity to fix what the court demolished. To put Litzman back in office, the coalition now plans to put new legislation in place that will legally allow a deputy minister to be put in charge of a ministry. They hope that with a specific law allowing such practice the court will no longer have a reason to interfere. Of course, to pass such a law they need a majority to support it — and it is not yet clear whether they have such a majority. But their chances are not necessarily bad for a simple reason: The grounds for opposing such an arrangement are not very convincing, unless one wants to deliberately pick a fight with the Haredi parties over something with little practical implication.

In other words: This is a fight about symbolism. And Israel is not usually keen on having such fights. That is one reason why the Kotel compromise scandal fails to anger Israelis (there is a platform, use it — as for symbolism, we have better things to do). That is also a reason for most of the public to not much care if Litzman is a deputy minister or a minister, as long as the job gets done.

Look at it another way: There are many reasons to be displeased with Haredi politics and its effects on the state’s policies. There are budgetary issues, matters of education, of participation in Israel’s economic life, the unfair division of the burden of military service, and the list goes on. Amid all these grievances, giving a Haredi politician the title he feels comfortable with — that’s an easy sacrifice.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.