One verse, five voices. Edited by Salvador Litvak, Accidental Talmudist

You shall not have pity: life for life, eye for eye, tooth for tooth, hand for hand, foot for foot. –Deuteronomy 19:21

Nili Isenberg

Pressman Academy, Judaic Studies faculty

My father (z”l) loved to tell this joke about a pirate who had a gold tooth, a peg leg, a hook for a hand, and a patch on his eye. When asked what happened, the old buccaneer was more than happy to explain each battle injury in chilling detail. But let’s cut to the chase: “And what about your eye?” My father would curl his finger into the shape of a hook and gesture toward his eye, cracking up himself: “Ah, well, me parrot pooped in me eye, and it was the first day after I got me hook!” Cue groaning.

If anyone needs to be served the justice of “an eye for an eye” (Rashi says the value of his eye) it’s our friends, the pirates. Yet, who wouldn’t have pity on the likes of Captain Jack Sparrow, for example, most dashing of all fictional baddies? If he took out my eye, I’d forgive him. But the midrash cautions, “One who is merciful to the cruel, in the end is cruel to the merciful.” The Torah wisely sets high standards for justice in our earthly courts.

However, with the High Holy Days approaching, even if we are as sinful as pirates, we can still pray for mercy in the Heavenly Court.

How does a pirate confess his sins to God? Search for “Pirate Viduy” on youtube.com, and let me know what you think. Hopefully you won’t want to take out my eye, tooth, hand or foot for creating it!

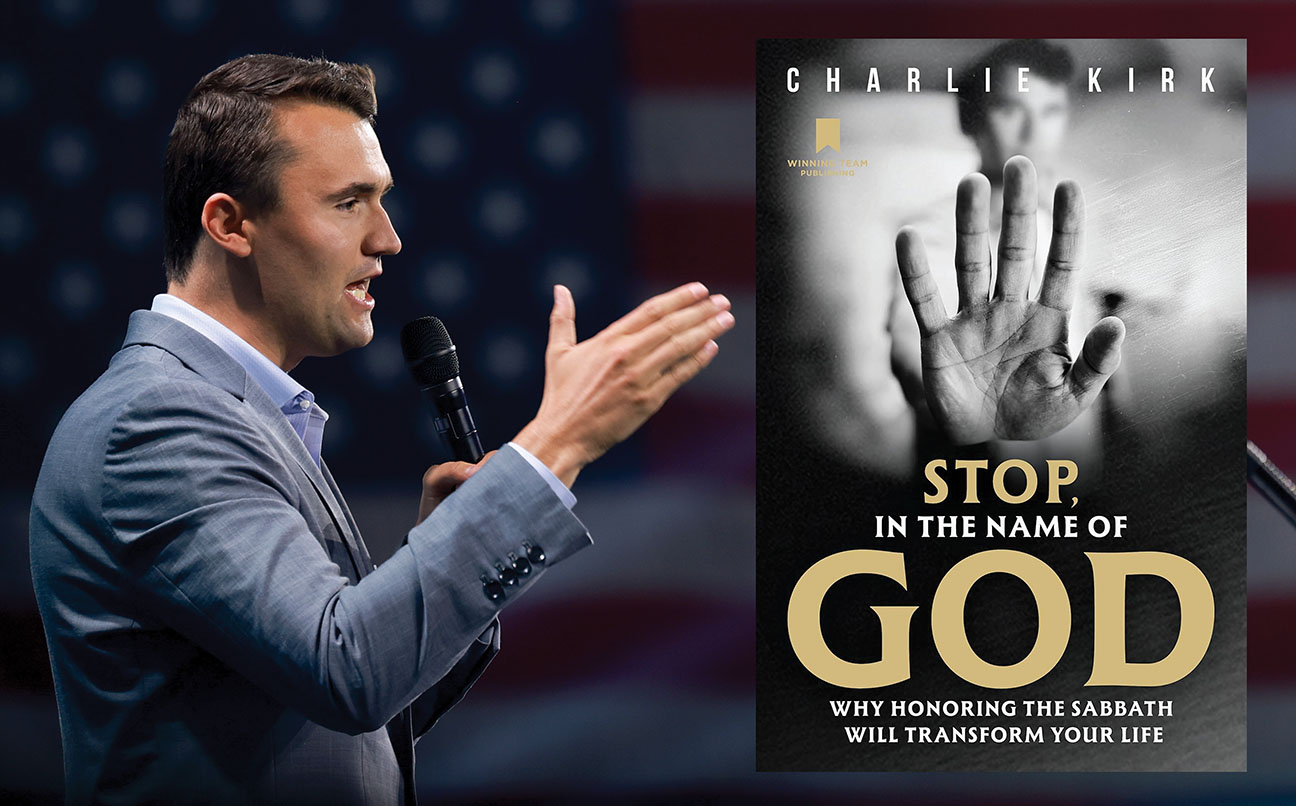

Peter Himmelman

Musician, author and founder of Big Muse

It’s challenging for most modern Jews to open a Chumash and read something as harsh as this pasuk (verse). So fierce is our love of kindness that these very words are likely to have turned many of us off from prayer in general, and from Jewish prayer specifically. Unlike mitzvot like tzedakah (charity) or visiting the sick, this one, which goes so far as to require us to forgo our sense of pity, seems cruel and well … un-Jewish.

But the Talmud, (tractate Makot) shows us a very different view of this pasuk, one whose essential aspect is indeed kindness. The pasuk refers to how one must deal with a particular type of false witnesses called adim zomemim. Adim zomemim are witnesses who were proven by two other reliable witnesses to have been in another place when an alleged crime was taking place. Their false testimony, a subversion of justice and truth to the extent that an innocent person could be put to death, is as grave a crime as murder itself. This is why the pasuk tell us, “You shall have no mercy.” And as we’ve seen in our own times, the subversion of truth ultimately threatens to destroy the fabric of society.

So rather than look at the pasuk as harsh or cruel, it might make sense to reframe it as something else entirely: a strong, but necessary bulwark against the brutality of falsehood.

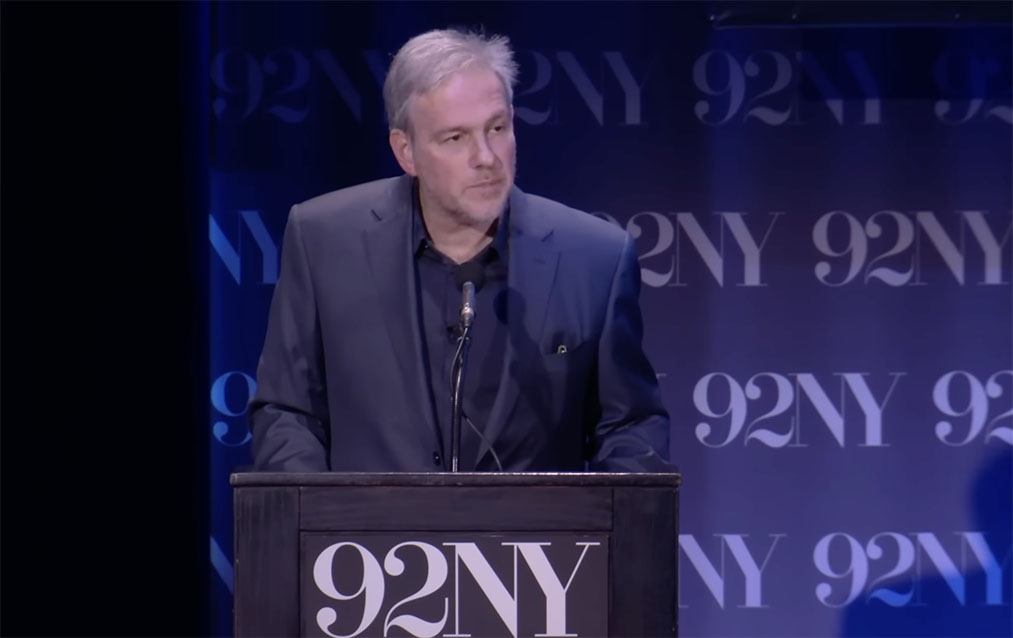

Michael Berenbaum

American Jewish University

This verse demonstrates an important concept, central to Judaism. Jews are bidden to take the Torah seriously, not literally.

Despite the admonitions in the book of Devarim, “do not add to it [the Torah] and don’t take away from it,” we do add to the Torah, interpretatively transforming its teachings.

Judaism is a rabbinic religion that understands Torah commandments through the lens of biblical interpretation, via rabbinic eyes.

Its most Orthodox justification, two revelations occurred at Sinai, one written — the Torah as we have it — and one oral, the interpretive tradition that enables us to understand the Torah’s meaning.

The interpretive tradition was an indispensable means for remaining faithful to the admonitions of the Torah while mitigating some of what future generations came to regard as the difficulty of actually carrying out its teaching. Thus, “an eye for an eye” is rendered as “monetary compensation” and “a tooth for a tooth, a hand for a hand, and a foot for a foot” likewise, while “a life for a life” is understood more literally.

A literalist reading of the Torah would certainly read the verse quite differently. Imagine an “originalist” reading, to borrow from a school of thought of U.S. constitutionalist interpretation.

Finally, no verse of the Torah should be read in isolation, so the introductory phrase “have no pity” is not a general principle. “The people of Israel are compassionate and the children of the compassionate,” the rabbis teach. Have no pity is thus applicable only the punishment for bearing false witness.

Rabbi Nicole Guzik

Sinai Temple

My friends and I joke that in life, there really is no instruction manual. Time and time again, the Torah proves us wrong. While not necessarily teaching how to walk step by step, the Torah clarifies when we must show mercy in this very confusing world of ethical dilemmas. Chizkuni, the 13th-century commentator, explains, “You shall not have pity with the guilty person; on the other hand, even during war time you shall display pity on people who are in the process of building their homes for the first time, be it if they are engaged to be married, that they are in the middle of building a house, or planting an orchard.” The lesson is palpable: there is a time and place to exact justice. But more often than not, we are meant to open our eyes to those that are trying to build, grow, plant seeds, and live life — even those we might call our enemies.

When someone is building a house, we can’t help but wonder who is inside. People, eating, sleeping, telling stories and making memories. When we see the planting of an orchard, we witness rebirth, the tilling of soil so that others will one day reap its harvest. It is much easier to open one’s heart when we get a glimpse of the way another opens theirs. Perhaps that is why Avot de-Rabbi Natan shares the challenge and difficulty: Who is a hero? The one who transforms an enemy into a friend.

Rabbi Tzvi Freeman

Editor of Chabad.org, author of “Wisdom to Heal the Earth”

The most precious friend is one who knows how to listen. Often you yourself don’t understand why you say what you say, but this friend listens to your words and hears there the hidden things of your heart.

Moses was God’s good friend. God said, “Tell the Children of Israel to sanctity every firstborn.” Another prophet would have the nation sacrificing their firstborn. But Moses? He tells the people to redeem their firstborn with a few silver coins.

And if somebody would have asked, “But Moses, is that what God said?” Moses could have answered, “That’s what He meant.”

God said, “Moses, let go of Me so I may destroy them.” Moses heard, “Plead on behalf of my beloved children and elicit My compassion for them.”

The same here. The Divine word crashes into Earth’s atmosphere: “An eye for an eye!” But it falls upon the soft, well-tilled soil of Moses and the sages, who tell us, “He means fair monetary compensation — as He said on other occasions.”

And if we ask, “But is that what He said?” they will answer, “In His Torah, as it is above in a world of the spirit, justice is achieved in perfect balance. Damage inflicted by any sentient soul comes back to that soul in exact measure. And so He says those words.”

“But our world cannot endure unmitigated judgment. Our world is built with kindness.”

“So here, justice comes as monetary compensation.”

God chose a good friend in Moses and his people. (See also Shelah, Mishpatim.)