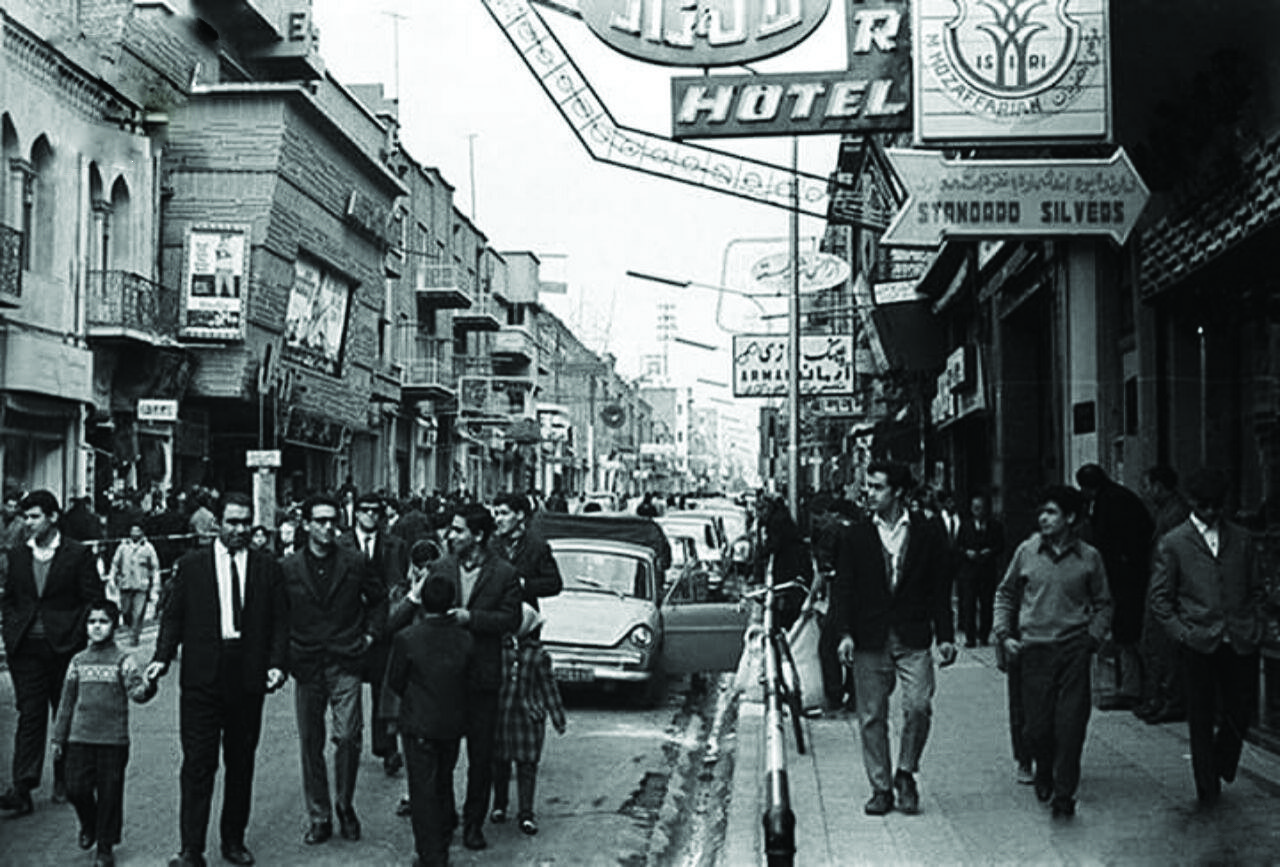

In our house on Shah Reza Street, the rooms were full of echoes. The hallways were long and dim and haunted by shadows. The garden — so vast I never thought I could find the edges alone — hid the ghosts of strangers who came alive in the moonlight and spoke to me till dawn.

In our house on Shah Reza Street in Iran, my grandfather Khanbaba Barkhordar, known to everyone as Aaghaa — Sir — walked around with his cane, always dressed in a suit, and commanded the servants as if to demand their soul. He was a tall man with great authority and boundless ambition. Among the first generation of Jews liberated from the ghetto, he had prospered under Reza Shah and spoke his name with the reverence due a god.

Aaghaa’s first wife, a Jewish girl from Kashan, had proven infertile, so he secured her permission to marry again. It wasn’t so much children he wanted but an heir — a boy who would carry his name and ensure that his legacy lived on. With his second wife, he had a son who died shortly after birth, two daughters and, finally, another son — my father — whom Aaghaa cherished most in the world and who was expected to produce (Aaghaa was adamant) many heirs of his own.

My father was 17 years old when he walked with Aaghaa through the doors of my mother’s home on Simorgh Street. He was a gorgeous boy, blond and dashing and dressed in a European suit with his hair greased back in the style of the time. “But she’s only 14,” my mother’s parents protested to Aaghaa when he asked for her hand in marriage. Peeking through the living room curtains, I am told, my mother saw her suitor and declared that it would be him or no one.

There was a fairy-tale wedding in the officers club in Tehran. Aaghaa invited a thousand guests, showered the bride with jewels, brought the newlyweds to live with him and his two wives in the house on Shah Reza Street. My parents had three girls. Aaghaa would have no heirs.

They were remarkable men, Aaghaa and other fathers of his generation. Born in Qajar-era, Iran, they had inherited 700 years’ worth of helplessness and impotence. They grew up as second-class citizens, considered ritually impure and forever under threat of extinction by hostile mobs loyal to one Shiite mullah or another. Most were poor; many forever hungry. All were forbidden by law to touch a Muslim or anything she wore or might eat, to go out on rainy days for fear that the rain might wash their impurity into the town’s water supply, to testify in their own defense in court, and to learn to read and write the language of the country. They were routinely beaten by Muslims in public places, verbally assaulted, belittled and denounced. They could be murdered by anyone for any reason; if punished at all, the killer would only pay a fine equal to the market price of a cow.

He couldn’t understand why his very large and varied collection of sons and daughters couldn’t merely do as told and be happy about it.

But the same society that was hell-bent on stripping these men of every shred of confidence or ability also imposed on them the obligation to be father not only to their own children, but to their siblings and in-laws and extended families as well. A man was nothing if he couldn’t protect and provide, lead and direct his own clan.

The second-born of five boys and a girl, Aaghaa was designated patriarch while still in his teens. Thanks to the Alliance Israelite organization, which had established schools in Jewish ghettoes, and to Reza Shah, who protected Jews and other minorities from the worst of the mullahs’ malevolence, Aaghaa became literate in French and Farsi. Newly married after World War I, he took his wife to Europe in search of business opportunities not only for himself but for his four brothers as well. Back in Iran a few years later, he tried to ensure that his two sisters married decent men who would take care of them properly; that his brothers received an education and made a living; that everyone’s children stayed on the straight and narrow so that the family name — the all-important, live-or-die-by family name — remain unblemished.

He tried, too, to withstand, with wisdom and honor, the savage onslaught of history: two foreign occupations that left the country’s economy in ruins; a famine that killed half the population and drove some to cannibalism; cholera and typhus epidemics that decimated families. He tried to gracefully accept and adapt to the tsunami of new ideas and modern practices — women’s rights, secular schools, children who thought they knew better than their parents. He succeeded more than he failed. That’s a testament to his strength and resilience and to that of all the men of his generation, who walked out of the ghettoes bearing the yokes of oppression and nevertheless managed to rise and prosper, learn and adjust, forgive and trust.

They succeeded more than they failed, but because each was father not only to his children but also to his wife and siblings, to their spouses and children, to servants who were lifelong employees and employees who depended on him for their families’ survival, the cost of failure for each was great and lasting, the weight of it ruinous to anyone with a conscience and a sense of duty.

In our house on Shah Reza Street, Aaghaa became old and ill and embittered by life’s disloyalty. His two wives had not proven to be as good at cohabiting and co-parenting as he had envisioned. Two of his brothers, whose education he thought he had financed by his own hard work and financial sacrifice, had used the money for a years-long junket in France; they returned to Iran unskilled and impecunious, bad boys who dressed well but couldn’t hold down a job. One of his sisters married a psychiatrist who turned out to have a few mental illnesses of his own. A granddaughter eloped with her Muslim math tutor.

Even in old age, Aaghaa was wealthy, elegant, ambitious and generous. He believed deeply in the value of education for girls as well as boys. He believed in treating the underdog with kindness, in lifting up the helpless. But he couldn’t understand why his very large and varied collection of sons and daughters couldn’t merely do as told and be happy about it. He didn’t see why women, once educated, should believe they knew better than a man; why God, having given him a son, was hell-bent on burying Aaghaa’s name. So he lit one unfiltered cigarette with the butt of another, stopped going out, and instead received all his callers at home.

I remember sitting next to him in the first-floor salon with the stone floor and the large French doors that opened onto the rose garden, watching everyone and listening to their tales. There was a dark-skinned, gaunt and shivery young man with a battered briefcase who came every few months to collect taxes; he left instead with a payoff and a promise that there would be more next time. There was a retired chauffeur, an emaciated, old opium addict who had lost his ability to work and came once a week only to collect his pension. There was a woman — “The Lady of Light,” Aaghaa called her ironically — who had married three times and buried each husband after each “accidentally” drank a glass of poisoned tea. Aaghaa was disdainful of the tax man. He tolerated the chauffeur. But it was the black widow whom he respected and reckoned with, although she was nothing like his idea of an “appropriate” woman, nothing like he would have wished for or tolerated in his family. She was, I believe, just another embodiment of the inherent contradictions and opposing forces that defined his time.

In our house on Shah Reza Street, Aaghaa gave his life, rather prematurely, to the cigarettes he was so fond of smoking. The world he left — 1960s Iran — little resembled the one he was born into. Like the single thread of spun silk that, when pulled, will set loose a constellation of knots, his death disbanded the Barkhordar tribe and gave each nuclear family at once the freedom and the burden to fend for itself.

Still in his late 20s, my father had been raised to obey and emulate the patriarch unreservedly. He was young enough to see the flaws and shortcomings in the traditional way of thinking, too old to entirely shake the old king’s shadow. He never once questioned or tried to shrug off his eternal duty to safeguard the well-being of every person in the family, but in the new, improved Iran, he didn’t have anything close to the absolute authority Aaghaa or other men of his generation had been able to wield.

It was a schizophrenic variety of fatherhood that my father and many men in modern Iran were expected to practice. They had all the responsibility but not as much sovereignty. They had to put up with parenting advice from pediatricians, psychologists, the government, schools and women’s magazines. They gave it all for their children to become more educated, worldly and aware than they had ever been. It was at once a source of great pride and exquisite tension.

In our house, my father was outnumbered six to one by women (not counting the old butler, the gardener and the opium-addicted chauffeur). There was Aaghaa’s first and second wives, both of whom would outlive him by a good four decades. Their relationship could have been the blueprint for the kind of “peaceful coexistence” practiced today by North and South Korea. Either one of them could have led an army through battle and lived to tell about it. There was my mother, headstrong, independent and unwilling to settle into the role of pretty wallflower. To this day, she believes and acts as if obstacles are made to be overcome; that the world is too slanted in men’s favor; that women, usually, know best. And there were my sisters and me, expressly raised by our parents to be bold and self-reliant.

My father never seemed to regret not having a son, never saw his daughters as anything less than men. Up until our 20s, he did expect us to obey him as fully as he had been expected to obey Aaghaa. His decisions for us were more right than wrong. When they were wrong, the cost was great and lasting. He had to live with this.

Even in Iran’s heyday, in the mid-1970s, my parents wanted their daughters to have greater professional and personal freedom than a traditional culture could afford. They moved to the United States when very few Iranians wouldn’t so much as consider leaving. They left their home, their established business, the reputation and social standing that was so essential to every family and individual’s sense of self. They left for a place where they knew laws and norms did not favor males nearly as much, where youth was valued above experience, children knew everything the minute they left the womb, and good parenting meant standing back and letting one’s offspring “make their own mistakes.”

For my father, from a selfish point of view, this was an illogical move. So was the decision of the tens of thousands of other fathers to leave Iran when the revolution gave them back all the rights and dominion that the shah and Westernization had taken away. For a great many of them, it meant settling into a life of irrelevance outside the home and a sense of ineffectiveness inside it. It meant giving their children leave to dispute and reject some of the most fundamental truths the fathers had known and counted on. Sometimes, it meant learning to accept the unacceptable — divorce, homosexuality, tattoos, nursing homes, religious orthodoxy and intermarriage.

It was an act of courage and self-sacrifice that, to this day, has not been sufficiently recognized.

So this year, on Father’s Day, to my father and his, and to all the other fathers of Jewish-Iranian men and women who have, for a lifetime, shouldered the task of looking after us no matter how old we are and how often we have disappointed them; who gave up or saw eroded their own godlike positions in the family but never abdicated their role as mentor, provider, rock and guardian-in-chief; who by leaving Iran, chose our future over their own; let me say, thank you.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.